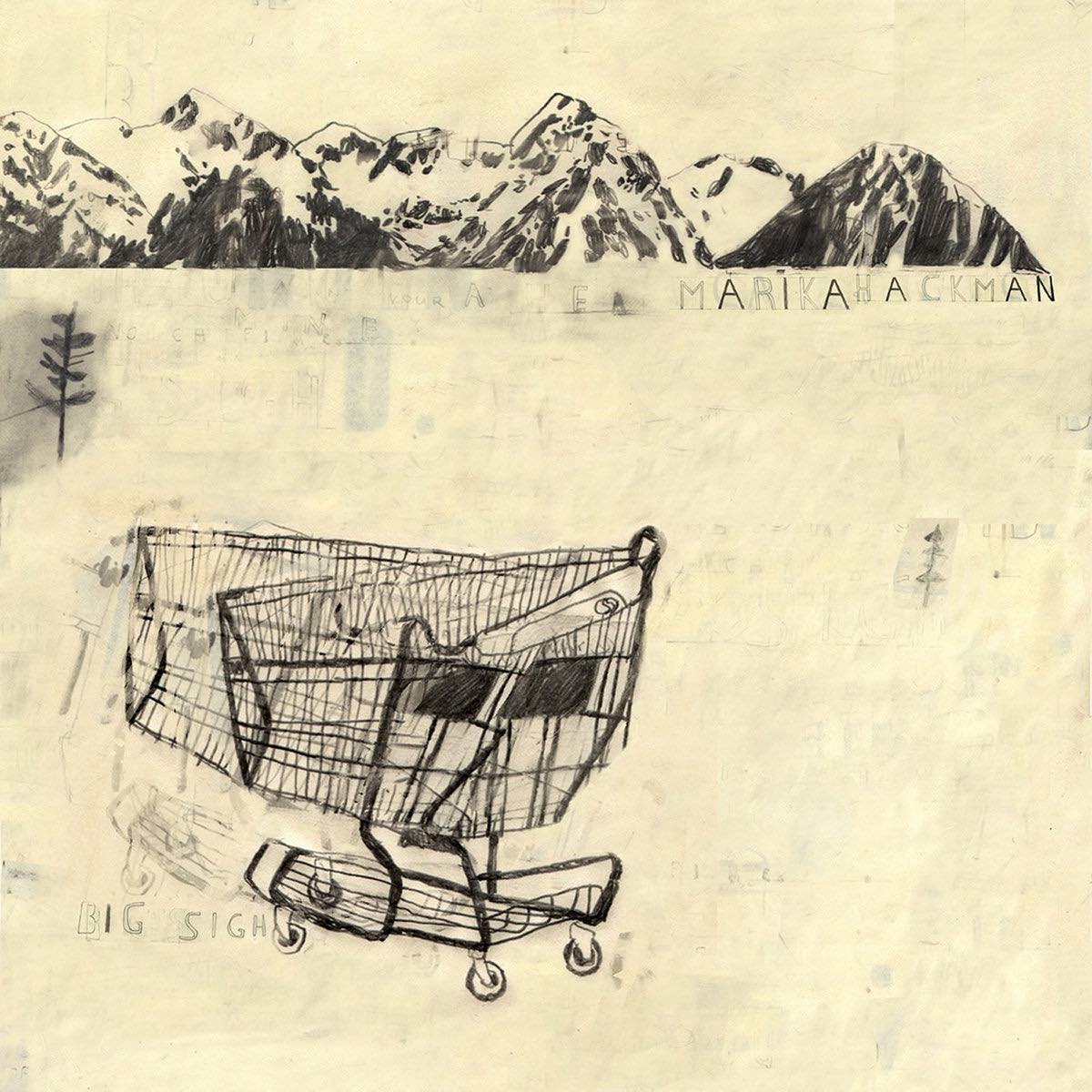

Marika Hackman

Big Sigh

CHRYSALIS

You can write yourself into boxes as easily as you can write yourself out of them. Big Sigh marks UK-based songwriter Marika Hackman’s fifth studio album, and you get the sense that there’s a fair amount of stock-taking going on for a musician now entering the second decade of her career. Hackman has always been a writer of big, sweeping emotions, but how those emotions have manifested has shifted over the years. What started as the kind of folkie, acoustic solo project you might expect from someone opening for Laura Marling has shifted to something grander.

So, too, has Hackman as a persona—especially on 2019’s Any Human Friend, which saw her embrace a kind of brash, queer sexiness that betrayed a growing confidence as a songwriter. On Big Sigh this same desire is almost always undercut with danger, sadness, and more than a bit of self-loathing, shifting the perspective once again. This isn’t an effort to discredit the levity and freedom of Any Human Friend, but rather to address the long shadow that can accompany such naked longing.

Perhaps no song better captured the thesis of her previous effort than “Hand Solo,” a rippling ode to masturbation that doesn’t mind providing a bit of shock to the unsuspecting listener. The closest thing we get to that unabashed carnality on Big Sigh goes a long way in establishing the difference at the core of these two records. “Take me in, open up and spread me thin / Feel around the brain in my legs,” sings Hackman on “Slime,” a song that both celebrates a budding sexual relationship but remains acutely aware of its nastier implications. In other places, Hackman is more direct about the undercurrent danger that defines many relationships. Vampirism has always invited metaphors for sex, and “Blood” is no exception.

Meanwhile, a song like “Hanging” addresses the self-loathing that so often becomes intertwined with desire. “My heart won’t grow / With your fingers down my throat… Somebody good shouldn’t be so cruel / And I know you don’t mean it, but I’m breaking like a wound.” This imagery hits hard enough on its own, but when matched with a sweeping, orchestral arrangement, as heard here, it becomes all the more menacing. Similarly, on “No Caffeine,” a good fuck is presented as just another solution to overwhelming anxiety, among a laundry list of futile solutions like herbal tea, screaming into a bag, or calling your mum. The freedom to address desire and sexuality head on is all well and good, but a fix-all it is not.

Any Human Friend may have been a relative breakout for Hackman, but her journey as a songwriter is not necessarily one of drastic change. Still, 10 years and four albums is certainly a point at which it makes sense to look back, something she seems keen to do on album closer “The Yellow Mile.” Hackman has deemed this a return to her roots, its hushed immediacy closer to her first full-length, 2015’s We Slept at Last, than her most recent one. Choosing to make this the finale of Big Sigh is an important clue as to where Hackman may choose to go from here. “The Yellow Mile” may, in fact, be the titular exhalation—not one of exhaustion or contentment, but landing somewhere in the middle. This record’s most impressive feat is not reinvention or perfection but in the way it holds all truths—even the ones difficult to reconcile—at once.