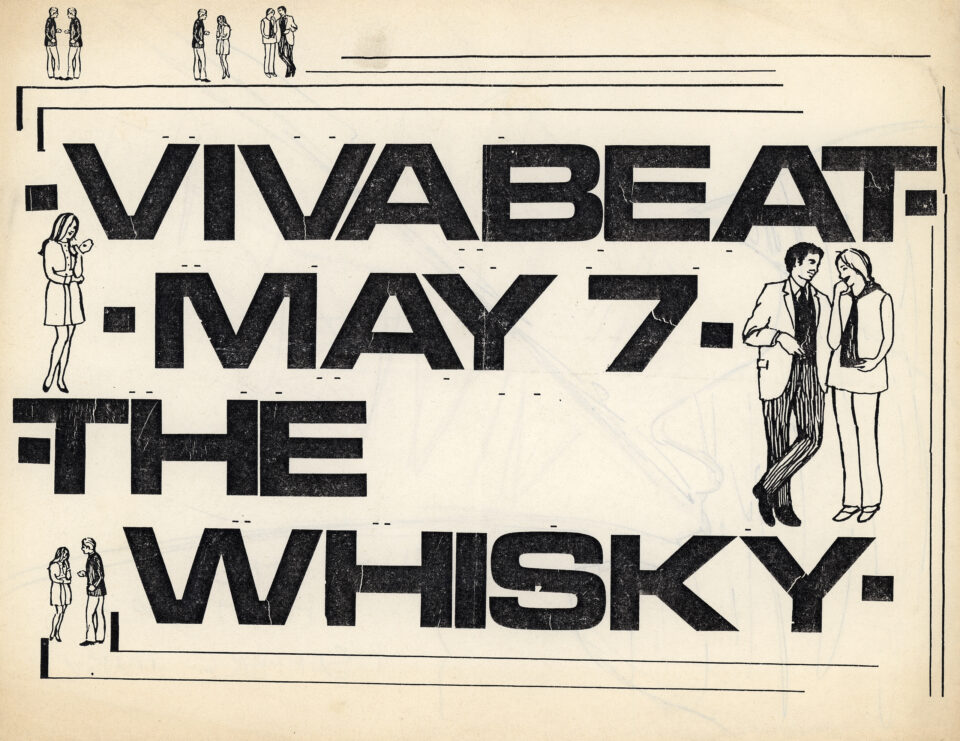

It was 1982, and the sold-out crowd for Gary Numan’s packed to-the-rafters show at Pasadena’s Perkins Palace was there early to see the opening band, LA’s own new wave trailblazers Vivabeat.

Barely in my teens, I somehow found my way from Huntington Beach to this revamped historic theatre-turned-punk-rock/new-wave venue, and clawed up to the front of the stage. Reared by KROQ, Southern California at this point was the new wave epicenter of the world, where the likes of Soft Cell, The Human League, Missing Persons, and Sparks dominated the landscape. Many in the room seemed familiar with Vivabeat already, while others were immediately drawn to their instantly endearing synthpop sound, led by the band’s captivating frontman Terrance Robay’s soaring voice and swaying blonde hair (shadowing Duran Duran and Japan’s David Sylvian). It felt like it was their time—but in less than two years, the group would dissolve, with so much promise unfulfilled.

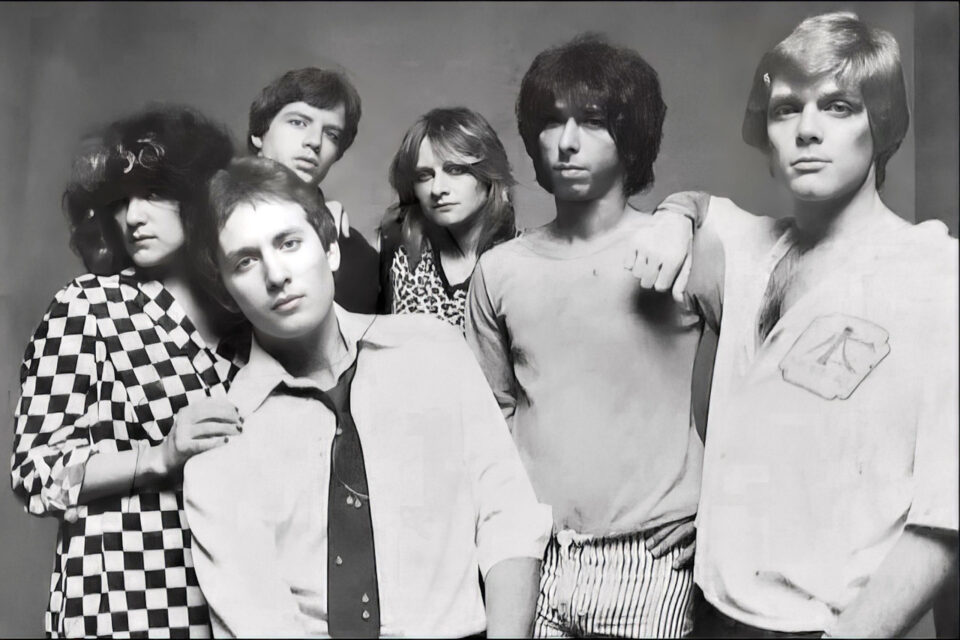

While their synth-heavy sound at that moment was reaching a commercial apex around the world, they’d actually been crafting their style for several years and were one of the first bands in LA to bring synthesizers to the forefront. Vivabeat first emerged in 1978 with a lineup including members from Masque club staples Backstage Pass (keyboardist Marina Muhlfriedel, a.k.a. Marina del Rey) and Boston’s new wavers Human Sexual Response (guitarist Alec Murphy), along with aspiring actor Robay fresh from his stint playing James Dean in a musical in London. Rounded out with principal songwriter/bassist Mick Muhlfriedel, drummer Doug Orilio, and keyboardist/vocalist Connie de Silva, the band caught the ear of Peter Gabriel, who helped get them signed to his label Charisma Records, and was said to have been so influenced by the whistling on their single “Man From China” that he added a whistling melody to his hit “Games Without Frontiers.”

Forty years after the band unplugged its last synth, Rubellan Remasters has just released the first-ever CD reissue of Vivabeat’s debut LP, Party in the War Zone, with the remastered original recordings along with 10 bonus tracks, and also released a separate vinyl-only release The House Is Burning – The Best of Vivabeat—both compelling testaments to a band you’re sure you know, but just can’t place from where.

To celebrate these releases and to learn more about the origins of this uniquely LA band, we asked Vivabeat’s Marina Muhlfriedel to recount the tale of the band’s earliest days. — Randy Bookasta

Decades before Vivabeat was shocked into reanimation by Rubellan Remasters, bass player and primary songwriter Mick Muhlfriedel and I often ruminated over what might have been. Peering into that extraordinary chapter of our lives, envisioning if only we could revisit our MIA 24-track masters. If only lead singer Terrance Robay was still alive. If only we had sharper management and spoke our minds in the studio. If only we hadn’t been so young and arrogant. Don’t get me wrong. Vivabeat brimmed with ingenuity, and I’m incredibly proud of all we created.

In one fantasy, I picture the Vivabeat saga as some parallel universe Broadway musical (score obviously intact) telling of the consummate ’80s techno-pop band fronted by a movie idol–gorgeous lead singer replete with tinges of David Bowie, Scott Walker, and Troy Donahue, taking a wild ride of incomprehensible fortune ensnared by staggering upheaval. Broadway or not, it’s a damn good story.

In one fantasy, I picture the Vivabeat saga as some parallel universe Broadway musical.

So it begins. A year before the illustrious ’80s were birthed, I worked as the entertainment editor of Teen magazine and was one day invited to an industry luncheon at Le Dome, a posh Sunset Strip restaurant. It was an Atlantic Records press event, and I was seated beside the guest of honor, Peter Gabriel. Truth be told, the arrangement was choreographed by publicist Jane Ayer, who thought Peter might like Audio Vidiot, the fledgling punk band I played in.

Peter and I struck up a conversation, and when it came up that I played synthesizers and keyboards, his attention sparked. He asked if he could hear what we were up to. That evening, at my Hollywood apartment, Peter clearly grasped what we were doing in our Roxy Music and Velvet Underground–inspired rough demos. He especially liked a song called “Man From China” that was threaded upon an indelibly haunting whistle hook. He told me to stay in touch and to let him know when we had updated demos.

Hearing what happened, my bandmates—guitarist Alec Murphy and singer Robert Windfield (née Garmen)—took it as a sign that we were onto something big. Alec went into high gear, calling bass player Mick Muhlfriedel, who he played with a few years earlier in Boston. He told him he had an amazing band in LA, that Peter Gabriel was into it, and, stretching reality, that a record deal was imminent. Mick needed to move to Los Angeles immediately. Mick contacted Boston band Reddy Teddy’s drummer Doug Orilio and synth player Connie DiSilva to see if they might also consider heading West.

Conveniently, the following week, I was going to New England to interview Van Halen for Teen. On my way home, I arranged a stopover in Boston to meet our potential bandmates and hopefully clinch the deal. As I relayed the Peter story, Doug—with his cool, Italian street vibe—and Connie—smiley and polite—were visibly bursting at their seams. Mick was cooler. Quiet, with killer blue eyes, I thought I saw him roll as I pitched the scenario. He needed to say yes. They all did.

Remarkably, Mick called Alec after the meeting, saying they were all chucking their jobs and current bands and leaving for LA.

Soon, Doug and his girlfriend Suzie set out across America with a pumpkin-shaped orange trailer large enough to hold his drum kit and worldly possessions. Meanwhile, Mick flew to LA during one of the worst heatwaves in history and moved into the front house of a duplex on Palm Avenue, a block from Gil Turner’s Liquor on the Sunset Strip, where Alec and his brother, guitarist David Murphy, worked. Actor Blackie Dammett (John Kiedis) and his son, 16-year-old Anthony, not yet of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, lived next door.

Before Connie and Doug arrived, we booked rehearsal time at a rundown, dimly lit studio. Our first attempt was with Robert, Alec, David, Mick, me, and a young drummer from San Diego, Chris Bailey. The songs were basic enough, and Mick, borrowing Chas Gray’s (Wall of Voodoo, The Skulls) blue Rickenbacker, quickly picked them up. It was easy to sense, though, that Robert’s pretense of being the band’s leader seriously irked Mick.

After rehearsal, a few of us—sans Robert and Alec—went to my apartment. Walking in the door, Mick announced that there was no way he could play in a band with Robert. He was packing it up and returning to Boston.

I knew in a flash, though, in every bone in my body, that couldn’t happen. Mick had to stay. There was a life, a band, and a story that needed to unfold. In a glimmer of clarity, I reached for his wrist and blurted, “You can’t go. Stay. I’ll leave the band, and we’ll start a different one.” He looked as stunned as I did but agreed to give it a try.

There was a life, a band, and a story that needed to unfold.

Audio Vidiot cleaved into two groups: Robert, David, and Chris kept the name, shortening it to The Vidiots, while Alec joined Mick and me in what would become Vivabeat. Doug, Suzie, and a roadie named Das soon turned up, and although we were just finding our way, we all sensed something compelling. It didn’t take long to find our dynamics, a unique cadence, and Mick began churning out songs.

A few weeks later, Connie showed up with a pair of mind-boggling synthesizers—a miniKORG and an EML 101. Along with my primitive but incredibly fun Roland monophonic SH3 (that I still have), Farfisa organ, and a Roland electric piano with a few cool sounds, Vivabeat’s keyboard underpinnings took a giant step into actuality.

I had heard so much about Connie—how she taught herself to play Genesis’s entire The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway album in a weekend. She was a DJ, a Buick heiress, and the daughter of the Mexican national water ski champion. Before Audio Vidiot, I was in Backstage Pass, a girl punk band. To me, Connie was a geeky girl who was a little too fond of doing the antler dance. Nonetheless, she was a frighteningly good musician and not a half-bad backup singer. I was glad she joined us, but was a tad intimidated.

We still needed a lead singer, and Terrance Robay was the dream candidate. He had just played James Dean in London, and his publicist set up a visit to Teen hoping to find him a place in our pages. There wasn’t enough to justify a story, but we couldn’t have conjured a more ideal fit for Vivabeat. Terrance had a brilliant voice, drop-dead perfect looks, and was an incredibly pleasant guy.

As soon as we wrote our first four songs, we booked time at an 8-track studio off Hollywood Boulevard and cut a new demo. I was ready to reconnect with Peter. A month later, I went to England, and ringing him from my London hotel, Peter invited me to a party at his home in Bath the following evening. I invited my friend, Rich Barbieri, the keyboard player from the band Japan (now in Porcupine Tree), and he agreed to drive.

It was magical—20 or so guests playing croquet by moonlight, surrounded by towering wormwood hedges and sipping peppermint tea. Saying goodbye late in the evening, I didn’t mention to Peter that I left the cassette demo in a fruit bowl on his dining room table.

Saying goodbye late in the evening, I didn’t mention to Peter [Gabriel] that I left the cassette demo in a fruit bowl on his dining room table.

Nonetheless, a month later, I received a pre-dawn morning call from Peter, introducing me to a jovial Brit named Tony Stratton Smith. Tony owned Charisma Records, the label for which Peter, Genesis, Monty Python, Van der Graaf Generator, among others, recorded. Strat, as he was known, said everyone in his office was whistling “Man From China” and that he had no choice but to take us under the “famous Charisma wing.” We became their first American signing.

This sort of thing did not happen, even in the ’80s. We knew dozens of bands, far more experienced and popular than us. Bands who struggled for years to get a second glance from a label. We played three gigs before suddenly finding ourselves at the Record Plant with Rod Stewart in the next room. We had clothing and equipment allowances. A famous director shot our first video. We signed with the William Morris Agency and were convinced we were on a trajectory to the big time.

Our first album, Party in the War Zone—featuring “Man From China”—came out in 1980. The song became a dance club hit in much of the world, and we got to lip-synch it at all the big gay discos. However, good fortune is often ephemeral. The fact that our first manager’s vanity license plate read “IM SPACED” should have rung a warning bell. It didn’t. Clueless, we forged ahead as he repeatedly dropped the ball. When two band members became heroin addicts and could barely perform, Charisma rejected our demos for a second album and dropped us from the label. And we dropped Connie and Alec from the band.

Soon, our drummer Doug crashed his motorcycle on Fountain Avenue. He was high with no helmet, and Mick found him listed as a John Doe in a coma at Cedars Sinai. He survived, but lost the use of three limbs.

Mick, Terrance, and I pulled together a funkier and more inventive version of Vivabeat with guitarist Rob Dean, who had been in the band Japan, and local session drummer Chris Schendel. We got another manager—and a record deal with Polygram—for a while. But while recording our next album, the manager went AWOL, not returning our calls. Once again, we were in rock ‘n’ roll limbo.

But all was not lost. A couple of dance club promoters released a limited-edition follow-up EP featuring a song called “The House Is Burning (But There’s No One Home).” The song became a European dance club hit and was picked up along with its video (which won an MTV award) to appear in the movie Body Double. Vivabeat was on track to live out a few more fab ’80s cocaine-fueled years, recording some of our strongest work yet. When Rob Dean left Vivabeat for Gary Numan’s band, Jeff Gilbert, a tech-brained San Francisco transplant who later became one of the wizards at Mackie, joined us.

Vivabeat never hit the great big time, but we got a whiff of its heady enchantment, making music we loved, going on the road with bands like Gang of Four, Human League, Depeche Mode, Gary Numan, Thompson Twins, and The B-52’s (R.E.M. opened for us). We also found a dream production partner in Earle Mankey, who got us like no one else.

Vivabeat never hit the great big time, but we got a whiff of its heady enchantment.

By 1984, the vision that was Vivabeat began to fade and, after a couple of spinoff bands, ceased to exist. In 2001, Permanent Press Records released The Good Life, a CD encompassing much of our music, giving it new life on streaming services and in TV and film.

Still, there hasn’t been a month since the band ceased playing that I haven’t replayed our rise and demise, still wondering what if only… FL

Three original members of Vivabeat, Terrance Robay, Alec Murphy, and Connie de Silva, died of AIDS. Doug Orilio passed away in 2021 from complications from his motorcycle accident injuries, and Jeff Gilbert died in 2019. These remastered projects are a tribute to their contributions.