In 2006, the American psyche was, well, let’s just say a bit fractured. The country was three years into its ill-conceived stumble of a war in Iraq and barely removed from the shattering effects of Hurricane Katrina—a storm whose devastation was worsened by the outright contempt shown by many in positions of power for the lives of the poorer, majority-Black populations that bore the bulk of the damages in New Orleans and all other affected areas. This deepened the worsening divides in American public life at the time, which today have evolved into Grand Canyon–like fissures in the nation’s collective consciousness.

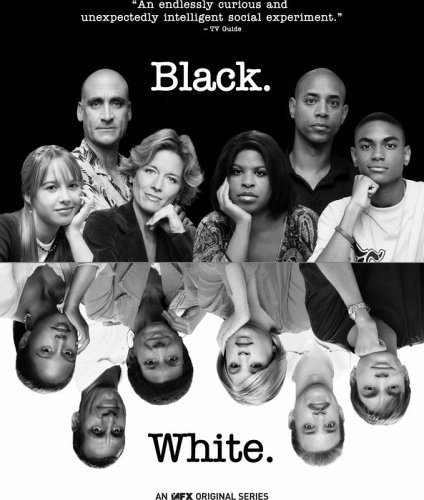

In the midst of these turbulent times, there was one man who stared into the void long enough to conceive of a show that could be the greatest representation of the brainworms on display at the time. That man was N.W.A-member-turned-family-movie-star Ice Cube, and his show was FX’s Black. White. For the uninitiated, here’s the conceit of the show: Two families—one white, one Black—would both live together in a house in Los Angeles. The white family, the Wurgels, would go out into the world in Blackface makeup while the Black family, the Sparks, would traverse the world in whiteface. I know what you’re probably imagining, and I promise you it’s worse than that.

In the LA Times review of the show, writer Greg Braxton begins his piece by commenting on the show’s theme song, stating that it was “both come-on and warning—‘Please don’t believe the hype. Everything in the world ain’t black and white.’ It also may turn out to be an unintentionally ironic commentary on the project itself.” While this is an interesting point, I myself am more drawn toward the final lyric in the title song: “If you’re a zebra, you better come out them stripes.” This better encapsulates the show, because the whole project is best summed up in two words: deeply unserious. The series is six episodes of racialized Lovecraftian horror of the first degree—not in the world-eating monster or mind melting existentialist way, but in the do-you-know-what-H.P-Lovecraft-named-his-cat way. In watching these episodes I felt somewhere between overwhelmingly horrified and amazed that it exists at all—almost like waking up from a dream of peeing yourself only to discover that you have, in fact, peed yourself.

It seems as if the show is better left rotting away in the waste bin of history rather than being trotted out again or (god forbid) remade. But to me, there’s a simple value to Black. White. that goes beyond memeability or pure shock factor. I think the fact that this show was made in the first place—and even won an Emmy (for best makeup, go figure)—is why we should revisit it. Its existence implies that some viewers were aware that a serious conversation needed to be had regarding race. This is a pre-Obama America, before people could pretend racism was solved for eight years, and it’s obvious that this show attempts to fill in the widening divide taking place at the time. And this is the problem.

This is a pre-Obama America, before people could pretend racism was solved for eight years, and it’s obvious that this show attempts to fill in the widening divide taking place at the time.

Take a step back and look at the situation: the conversation on race in America is being conducted by two families cosplaying the other’s race with the incentive to be as extra and outlandish as possible to drive up revenue and ratings. It shows exactly how under-prepared America was (and remains) for a true understanding of the racial dynamics that have been present in this country since its founding.

As ridiculous as the show is, it does seem to have at least a bit of self-awareness. The producers seemed to want to move away from the documentary label so as to allow for more flexibility with the edits, keeping the more salacious parts in. The most disturbing aspect is that even without any perceived revenue-driven editing it seemed the show had plenty of controversy to stand on.

We meet the families in episode one, and immediately it’s obvious the fathers are going to be a problem. Bruno, the patriarch of the Wurgel clan, is quite possibly the most chaotic force of racism ever set to film. While sitting down to the first dinner of the series with the Sparks shortly after meeting, Bruno says the following words: “I’m waiting for someone to come up to me and say, ‘Hey, n*****’”—in doing so showcasing his (and by extension the show’s) very elementary understanding of racism. On the other hand, Brian, the Sparks’ patriarch, goes on a soliloquy about the struggles of growing up with light skin and green eyes that wouldn’t be out of place as an intro for a Logic song.

Much of the show’s early tension surrounds the relationship between Brian and Bruno. Brian in whiteface takes a much more playful approach early on, like going golfing or being overjoyed at receiving good service while shopping. Bruno, on the other hand, believes he’s solved the issues of racism that plagued the minds of James Baldwin and bell hooks. He decides after receiving decent service at a car dealership that if Black folk were just a bit nicer, then white people would be nicer back. The relationship between Brian and Bruno is honestly a masterclass in the many weird ways that masculinity has severely racialized definitions that show up in such scenarios.

What the show stumbles its way into is the understanding of the inadequacy of white liberalism to address the actual systemic racism that Black people experience. The show arrives at this point in the most profoundly stupid ways possible. Take, for example, a very telling moment that takes place during episode two between the mothers of the families, Carmen Wrugel and Renee Sparks. While working with a “racial dialect” coach, Carmen calls Renee a bitch, claiming to think it was a term of endearment among Black women.

The conversation on race in America is being conducted by two families cosplaying the other’s race with the incentive to be as extra and outlandish as possible to drive up revenue and ratings.

This comes after Carmen waxed poetic in the first episode about how open-minded her parents were while also repeatedly admitting that she wasn’t in contact with very many Black people on a personal level. When confronted about it by Renee later on, Carmen ends up crying while Renee is painted as some sort of aggressor. This gets across the inverse of the Brian/Bruno relationship by showing the racialized components of femininity and showing who’s allowed to express which emotions.

At this point you might begin to think that some actual analysis is going into this. But all of the ideas that could be developed in the show are picked up and quickly dropped in order to move on to more outlandish happenings. America isn’t interested in the deeper threads that first sowed our division, but more so in the profit that can be derived from exploiting that division. This is why we should watch Black. White.—to explore all the conversations we’re not having. What we see in the show is an accurate reflection of the childishness that is present in this country’s understanding of race, and watching it played back for us is as jarring as singing your favorite song only to have the music suddenly stop.

As uncomfortable as it is to ponder, this show exists as it is for a reason. While it’s a quite literal skin-deep examination of the forces that make up a racially divided country, it’s also a mirror. Black. White. was inappropriate, reductive, and—to a certain point—vile, but it was however unintentionally very much the best conversation on race that America was capable of having then, if not now. And what does that say about the state of the country and its future? FL