Few musicians get to be a member of a beloved and significant band—but Peter Hook has managed this feat twice. He was a founding member of Joy Division, who only recorded two full-length studio albums before vocalist Ian Curtis committed suicide in 1980, though they’ve long been credited with pioneering the post-punk movement. Unwilling to continue on as Joy Division without Curtis, the remaining members (along with keyboardist/guitarist Gillian Gilbert) formed New Order, who put a lighter, synth-pop sheen on their sound while going on to achieve worldwide success. Hook’s high-pitched, melodic bass playing was a distinctive feature of both bands, and many other musicians have long cited him as a key influence.

But in 1993, Hook left New Order. He rejoined them in 1998, only to depart again in 2007—and this time, the split was acrimonious enough that the sharp rift between Hook and his former bandmates persists to this day. In 2010, he formed Peter Hook & the Light, with whom he not only plays bass, but also handles lead vocalist duties. The band has frequently toured the world, specializing in performing Joy Division and New Order albums in full. They’ll do so again this year, kicking off a month-long North American tour on August 31 in Toronto. This time, Hook and his band will perform both Substance albums, the compilation LPs that New Order and Joy Division released in 1987 and 1998, respectively.

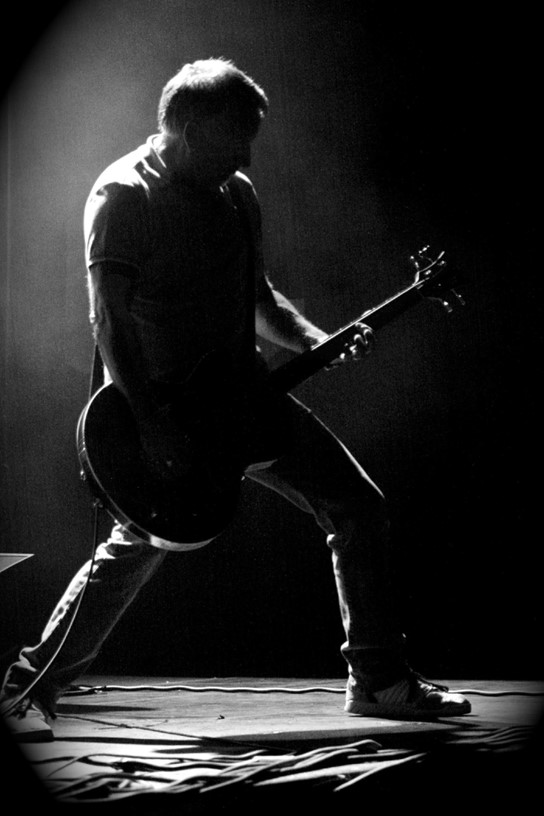

During a recent video chat from his home in Alderley Edge, England, Hook is affable and chatty (and sometimes bluntly candid) as he talks about how Peter Hook & the Light is honoring the legacy of both of his previous bands.

How does it feel as you gear up to play both Substance albums?

My ambition is to play every song ever written and recorded by Joy Division, which I’ve done. And my next ambition is to play every song I’ve recorded and written with New Order. So I’m well on the way. It’s very satisfying, and I get reminded that some people do love me, which is always nice to be reminded of!

Does playing these songs bring back any kind of nostalgia or particular memories for you?

It’s nostalgic every time. Because of what’s happened to New Order—maybe [that] isn’t the sunny episode, because of the troubles we’re still having. But Joy Division, luckily, is pure, and is backstabbing-free. So I usually can drift off into pure enjoyment doing Joy Division.

How did you know what direction you wanted to take with your playing and songwriting in the first place, so that it would be distinctive?

When we started, all Barney [Bernard Sumner] and I did was ape the punk bands that we liked, musically. When Ian Curtis got involved, he was much more musically educated than me and Barney, and it was him that turned me on to krautrock and The Doors. Iggy Pop. Lou Reed. I remember when we got a review and they likened us to The Doors—Barney and I had never heard The Doors. Ian lent us a Doors record and we sat there and went, “Oh my God, we do sound like The Doors!” So it was quite a surprise to hear that you had an influence without the influence.

“When you watched Ian perform, it was like watching Iggy Pop. Man, he was just cut out to do that.”

After that, we never talked about music when we were writing. We just used to jam. The interesting thing with Joy Division was that everybody wrote their own parts. Ian did the vocals and the lyrics, and I did some early lyrics and early vocals. We each sort of grew organically at the same time. And I must admit that from a writing point of view, Joy Division were very equal, as in splitting the money and everything between the four of you. Without each member, there would have been no Joy Division, without a shadow of a doubt. It wasn’t like that in New Order. Because we didn’t have Ian, we all used to chip in for the lyrics and the melodies and sort the vocals out together, which led to a different dynamic.

How did you know that you should try to be a musician in the first place?

It looked a lot more fun than working. When I saw the Sex Pistols, I thought they looked like they were having a great time. And I’d been to see Led Zeppelin the week before. Led Zeppelin were a fantastic band and I love them, but the thing is that at 20 years old, the Sex Pistols spoke to me directly. That confusion, that anger that you felt, that uncertainty of what you were going to do with your life—what you were going to do tomorrow—that you only feel as a teenager. I got why Johnny Rotten was screaming “fuck off” at everyone, because that’s how I felt. So I thought, “I want to scream ‘fuck off’ at everyone! I’ll buy a bass guitar and we’ll form a band and then we’ll scream ‘fuck off’ at everybody!” Which is what we did.

How did you decide to play bass? Why not play something else, or become a lead singer?

I didn’t have the confidence to be a singer, so I thought I’d hide behind a guitar—which I’ve been doing successfully for 48 years. If I haven’t got a guitar on, I feel absolutely naked. I used to watch Ian Curtis onstage with his wonderful stagecraft. When you watched Ian perform, it was like watching Iggy Pop. Man, he was just cut out to do that. Absolutely cut out. He had a lot to say—and I suppose, in a funny way, he knew it. He only ever wanted to be a singer. So that’s interesting, isn’t it? I’m a singer by default. But yeah, he wanted to be the singer, and my God, when he did it, he was absolutely 100 percent—if not more—wonderful at it. His words still speak to people. He still has a very profound effect, as does Joy Division, on first time listeners, which is great.

“I thought, ‘I want to scream fuck off at everyone! I’ll buy a bass guitar and we’ll form a band and then we’ll scream fuck off at everybody!’ Which is what we did.”

What do you think he would think about how legendary Joy Division has become?

Whenever we got down because we couldn’t get gigs or everybody hated us or whatever, he was always the one who used to sit us down and go, “Listen, don’t worry about them. We’re going to be fantastic. The music’s fantastic. We’re going to go all around the world with it. People are going to be in awe of what we’re playing. Don’t worry. All we have to do is just keep going.” He was the one that used to pick you up by the scruff of the neck—which is ironic because he’s the one who suffered enough to take his own life. Which I suppose doesn’t make you feel great when you realize that he was picking us all up by the scruff of the neck, but we weren’t picking him up by the scruff of the neck.

What do you think of the legacy of both bands?

Now I have the freedom to look at the whole catalog that I’ve written and play it how and when I like, whereas when we were together in New Order, we ignored Joy Division completely. And we also ignored all the old catalog, because Barney didn’t want to play it. You can’t make your lead singer play songs that he doesn’t want to play. It’s a funny position to be in, isn’t it? Four members of a group that have been together for 30-odd years—it’s like any relationship or any marriage or whatever. People change over time, don’t they? They get different ideals. I would like to hope that the other three members of New Order are as happy as I am doing what I’m doing. Maybe one day I’ll find out. FL