Since forming in Bowling Green, Kentucky, almost two decades ago, the members of Cage the Elephant have accomplished everything from multiple GRAMMY wins to countless soundtrack placements. But nothing prepared the band for the mental health struggles that guitarist/vocalist Matt Shultz experienced during the pandemic, which culminated with a January 2023 police encounter at a hotel in Manhattan where he was arrested on gun charges.

However, instead of that being the end of the story, it was a new beginning for Shultz, who realized that he’d been experiencing medication-induced psychosis and was able to get the help that he needed. The experience also largely figures into the band’s newly released sixth full-length Neon Pill, which was written both before and after his psychosis and has meanings that jump between these two versions of reality.

We caught up with Shultz to hear his account of what he went through while also discussing the fragility of the human mind and how he was able to channel his experiences into songs that are as relatable as they are revelatory.

In addition to being a music journalist, I also work full-time as a therapist and find it really fascinating the way you worked your mental health struggles into the album in such a poetic way. What was the lyric-writing process like for you for this album?

Much of the lyrics were written while I was actually in psychosis. At that time, the lyrics had a profound meaning to me. Obviously, once I was well into my recovery, coming back to them, that meaning totally shifted and many of the songs’ profound meanings had no basis in reality. So I had to kind of decipher what the songs were about, and for many of them it was about finding the sentiment in the song and then reapproaching from that place. There were some lyrics that were left as-is—I think that’s where some of the more colorful turns of phrase came from. But, yeah, it was really interesting looking at these lyrics and knowing the little nuanced meanings I’d attached to them.

“Float Into the Sky” almost has this dissociative vibe, lyrically and musically. It feels very atmospheric, as well.

Writing it, at least, I think I felt very isolated and I was really having trouble communicating how I was feeling or where I was in thought and mind. I decided to kind of take this Mother Goose approach and tell a story through things that almost had a storybook-esque surface to them. That song is definitely confronting isolation and at this deep feeling of lonerism. Going through what I was going through, I was completely unrelatable to most of the people who were around me, and trying to relate was a real battle. It was difficult.

I’m curious what you found helpful. Was it talk therapy or outpatient programs?

A little bit of all of it, really. The place where I was hospitalized was a partner with McLean Hospital and Harvard, so all the clinicians there were absolutely incredible. That was a big part of my recovery, for sure: just getting back to a place of good, healthy reality testing. Then from there, outpatient and talk therapy—I did that for about six months, as well.

“I don’t think I can talk about the music without talking about what happened, because the two are so deeply intertwined.”

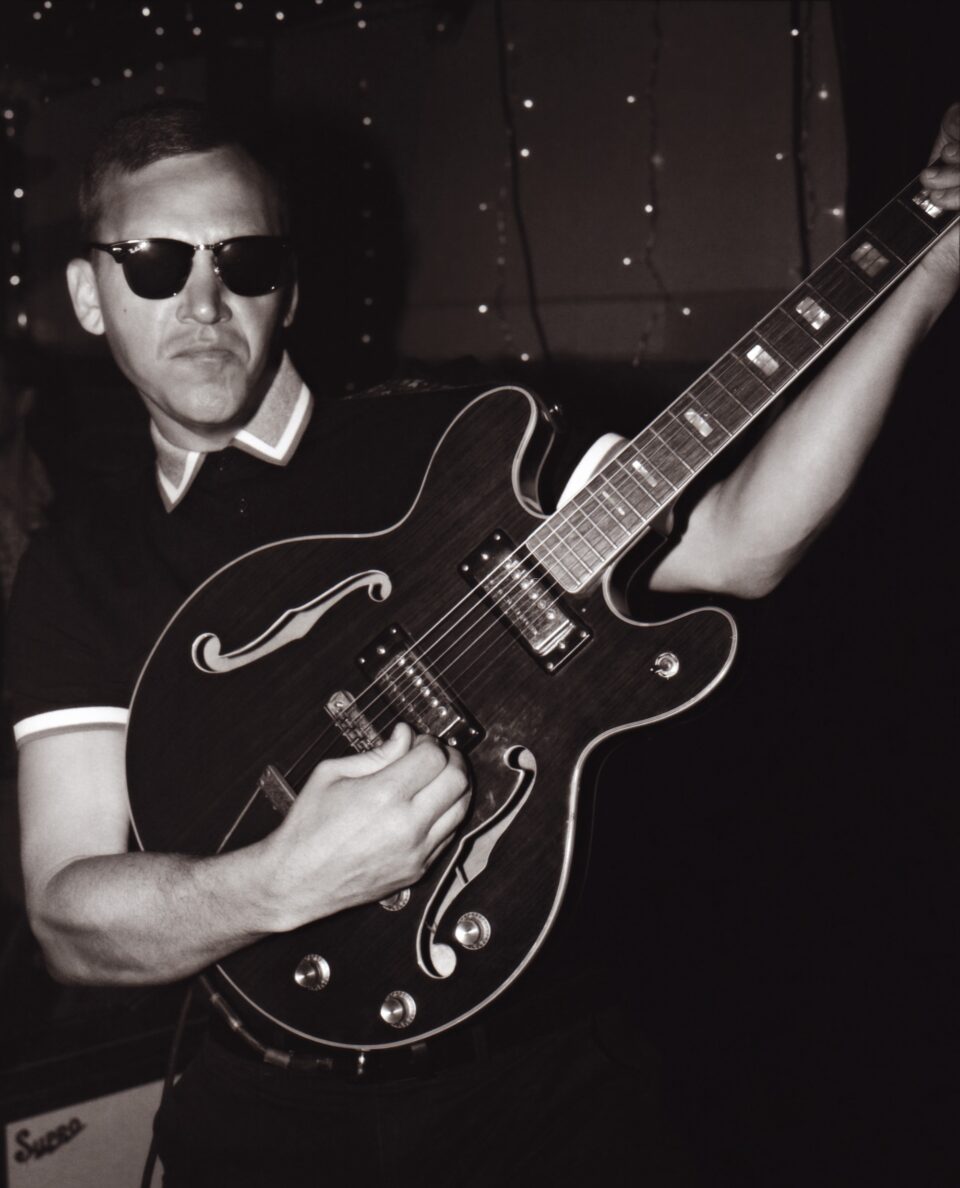

Brad Schultz

Matthan Minster

Another song that really stands out is “Rainbow.” Where were you at when you were writing that song?

“Rainbow,” I believe, was the very first song we wrote, and that song I wrote about my wife. She stuck through me through thick and thin, through everything I went through the past couple of years, and is a tremendously loving person. To call her a hero is an understatement. But sometimes I find the parallels in life between the ones I love and God, and God being love. So it was really this song about the genesis of love and continuously being lifted up by that. It’s one of my favorite songs on the album.

What was it like making the album at Sonic Ranch in Texas? I know it’s supposed to be this really unique and beautiful setting to record.

Sonic Ranch was amazing. One of the awesome things about that ranch is if you get stumped on anything, you can just jump on an ATV or a four-wheeler or dirtbike and just go for a cruise around this farm [laughs]. Drive down to the border, hang out by myself for a little while, do some reflecting, and then head back to the studio. I definitely went mudding at times, which was kind of funny. I’d never done that before. I’d leave the studio and come back covered in mud.

The album art is also really striking and has a lot going on. How did that come about?

Neil Krug is one of those artists who puts his entire being into everything he does. He’s an all-in type of creator where he’s wanting to have multiple conversations and conceptualize. We committed to this frame of thinking that we didn’t necessarily have to create the cover at any particular timeline, and we didn’t need to decide until it chose us. We were just looking through some of his work and some of the ideas we’d been working on and I saw an older piece of his and was immediately captivated by it. What I liked was the suspension of reality, almost as if it were this alternate universe. The thing I love about how it ultimately ended up is it almost looks like looking through the lens of my perception at the time. We didn’t want it to be too on-the-nose or have anything to do with pills or anything like that. But what I liked about it is that it was almost a weird pharmaceutical advertisement. Like, “Take this and this is how you’ll see reality.” It’s just incredibly striking at first glance, as well.

I’d imagine you have a complicated relationship with pharmaceuticals at this point, since they can help people but also induced your own psychosis.

I have no judgments whatsoever. Honestly, the medication that caused the psychosis I was in works for a lot of people. Maybe I phrased that wrong: I suppose what I was trying to say was it was just interesting because it was like looking through the lens of what maybe I thought the medication would do for me. It’s incredible how fragile the human mind is. I had no clue that I could take a medication and even remotely be entertaining the type of narratives I was, and to be as paranoid as I was, and hypervigilant. It’s actually kind of fascinating. I mean it’s terrible, but fascinating.

photo by David Iskra

I read that you carried around a lot of notebooks when you were writing for this album. Is that something you still do?

Yeah, I definitely still have all my writings and try to stay very active—I definitely journal differently than I did when I was sick. And it wasn’t just my journals. I tried to keep as many of my belongings around me as possible at all times. Just kind of constantly being afraid that somebody was trying to infiltrate my life. It was actually pretty sad. I’d go to restaurants with two or three large suitcases and it was pretty debilitating, to say the least. I definitely don’t travel like that anymore. Actually, after I was much better, while we were in the studio, it was kind of a joke. Like, “Where’s the suitcases?” [Laughs.]

What do you think were your motivations for coming out and talking about your mental health struggles more openly? Is it to help others?

I definitely hope that it’s helpful, but I think a big part of it is also that it was so all-encompassing—it touched every area of my life. I don’t think I can talk about the music without talking about what happened, because the two are so deeply intertwined. And I do hope that someone gets something out of it; there’s definitely warnings to heed whenever taking a medication. Obviously it’s all about the medical professionals who are working with you and making sure you’re in good hands—and also just for encouragement, because I know personally I was having this sense of isolation when I was sick, but even more so after I was well into my recovery and had the arrest. It was very much like someone had hijacked my mind and my body and had been living a certain way for a number of years, and then I’d come out of a coma to this nightmare. And that was tough at first, for sure. I definitely felt like maybe I went through something that no one else had, and that’s just not the truth. While it is rare, it’s more common than you’d think.

“It was very much like someone had hijacked my mind and my body and had been living a certain way for a number of years, and then I’d come out of a coma to this nightmare.”

You’re going to be touring a lot this summer. Do you have a self-care routine when you’re on the road?

I just exercise. Also, just being around a great community and embracing life—kind of a second lease on life. Really what I’m most focused on are the relationships in my life right now. That’s what brings me happiness and keeps me well, and I feel very fortunate to be where I am. I 100 percent have no doubt that had I not gotten off that medication there would be a good chance I wouldn’t be here, so I’m feeling super blessed to still be alive.

I mean, being back on the road itself and touring, I think, will be really great for me. It’s been a staple of my life for 18 years; we’ve toured so much that in some regards, being on the road is more like being at home than being at home. Also, one of the things that’s so surprising to me is that while a medication can have a profound effect on your mental health, the suspension of that medication has just as profound an effect. So I’m enjoying the fact that I’m getting back to a normal life. It’s actually incredible. FL