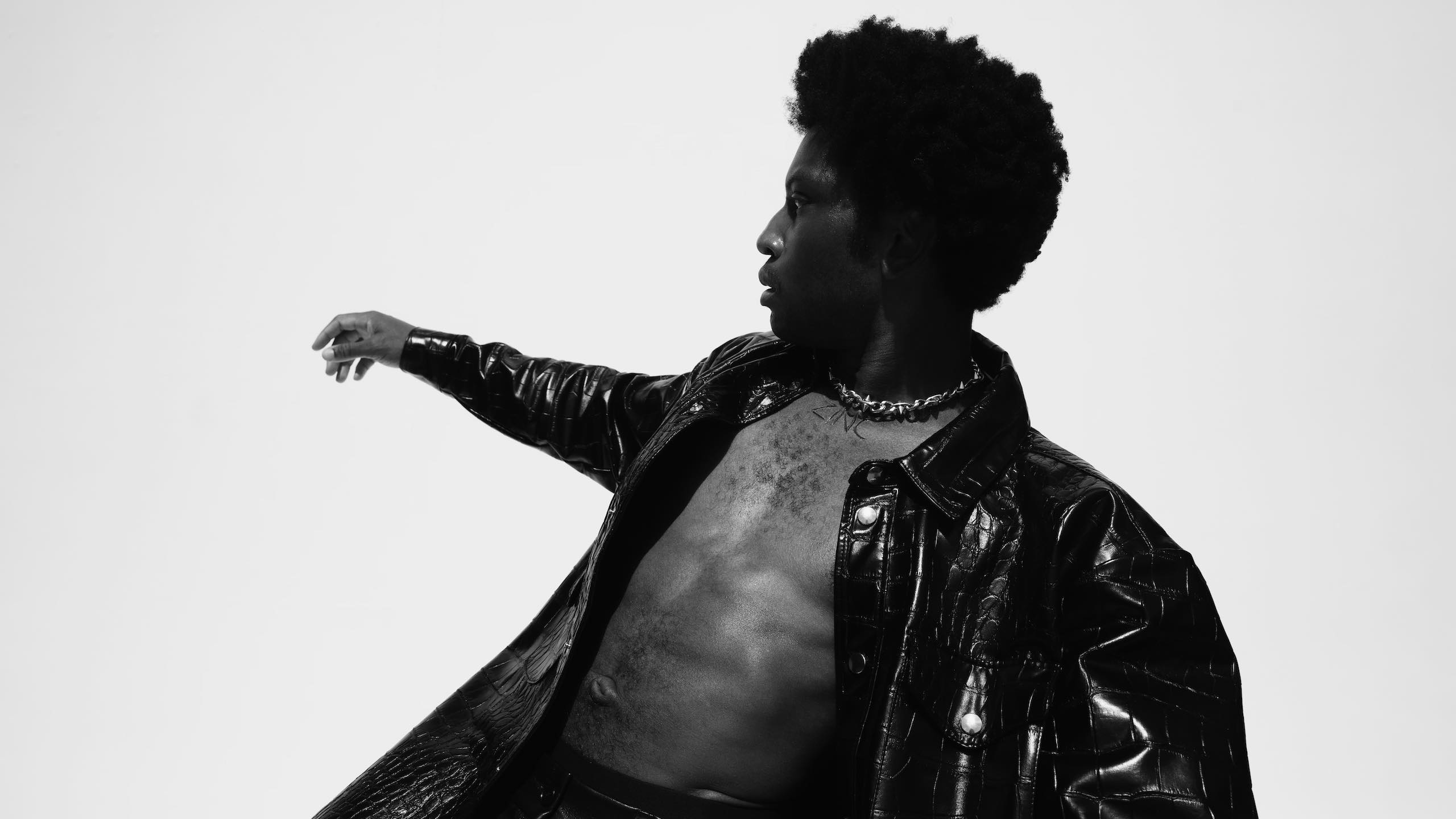

Gallant shows up to the hotel suspiciously close to Times Square ready to shred Fashion Week. Clothes have once again taken over the city, and while Gallant is in town to promote his new album Zinc., he’s also here to take in some of the looks. He rocks a leather jacket that seems extremely toasty—something I would sweat buckets in. Gallant? Cool as a cucumber. His boots would send my feet into intolerable cramps, but as far as I can tell, all his toes are situated exactly where they should be. Gallant is extremely casual and obviously so, but it doesn’t come across as inauthentic or even trying. This blend of laid back chill with radiating swagger is pretty much what makes Zinc. work so well.

Gallant was able to get to this place, he explains, because he made exactly the album he’s dreamed of making for a number of years. By his estimation, it’s the album he would’ve wanted to make after his 2016 debut, Ology. Following that album’s release and acclaim, he began working on his sophomore effort when the label he was working with got bought by Warner. His process got thrown off, and though given some room to operate, he felt that his vision was co-opted in favor of adhering to certain metrics. “When you go from a one-person company to a big corporation, the bottom line becomes more important,” he explains. “Everybody has to do this blanket thing. It was really tough.”

Part of the freedom Gallant felt while working on Zinc. came from exiting that situation, but it also came from opening for Sufjan Stevens on the Carrie & Lowell tour nearly a decade ago. In playing those shows, he witnessed an artist who never compromised his vision and was plenty relatable to fans, no matter how personal the songs got. He wants his work to be cherished in the same way. “His is the paradigm that I want to exist in. It can be done. He’s doing it. I might have other challenges that come with other things, but if I can break through and stay true, then maybe I can get to this level of being comfortable in my own existence and on my own path.”

With the new record out now via Mom + Pop, read more of our conversation below.

How are you feeling with the album about to be released?

I’ve never been more nervous in my life, to be honest. My heart’s been beating so fast for the past month and a half, but I think it’s good. [Zinc.] is so representative of me that if someone hates it, they kind of hate the core of my essence [laughs].

You’ve spoken about this being the record you wanted to make after your debut. Why weren’t you able to make that the first time around?

People say about your first book that you have your whole life to write it. Then, when it’s time for the follow-up, there’s not a lot of time, not a lot of preparation. I was signed to a label that my friend started, Mind of a Genius, and he was the only person that ran it. It was very small and he was my management, too. He really understood me and saw what I was doing, and wanted to use my uniqueness as a strength. His label got bought by Warner. All the people at Warner—they’re great people, they all have good intentions. But when you go from a one-person company to a big corporation, the bottom line becomes more important. Everybody has to do this blanket thing. It was really tough.

I felt like I didn’t have the tools I needed, even if they weren’t really effective and they were just security blankets. I felt detached from my own identity. Records wouldn’t come out unless I hit certain metrics. So even within that, I was working within a framework, parameters that I had to exist within. If this thing didn’t fit perfectly, it wouldn’t get the greenlight. A little bit of the childlike joy was gone.

“It’s always tough when you have an idea for something to exist and it doesn’t come out the way you want, but it’s not your fault.”

You were compromising.

That’s the biggest thing. Nobody was telling me I had to do A, B, and C and nothing else. There was a lot of wiggle room, but changing at all isn’t what I wanted to do. Everything was just a little watered down. That’s what made it tough. Psychologically, it was a little challenging. It’s always tough when you have an idea for something to exist and it doesn’t come out the way you want, but it’s not your fault.

You keep your production circle tight on the new album. What went into that decision?

Even though I’m a very scientific person, it makes more sense to operate when you’re making things on a purely emotional level. You can’t explain that to somebody you’re an acquaintance with. If you’re on the same page, you can sit in silence forever. That’s when it feels locked-in. You do something, it sounds like garbage. You laugh for an hour about it, make jokes, and then you make something that’s good—and it might reference the joke thing that you made. There are so many intricacies that only come from locking in with somebody that I really trust, especially as an introverted person.

Is it easier to express yourself musically than through speaking?

I’ve gotten better at talking, but I really don’t like speaking at all. People used to say I would only say one sentence in an entire day. When I was a kid, I felt like there was a bit of a barrier between me and the world. Making music was the way I expressed myself, culturally. If somebody liked it, it was like they understood me. When I was starting, if there were three people in the crowd and they got it, it blew my mind. To get connected with that community and then tour and meet those people in real life completely transformed my whole relationship to the world.

What did you learn while opening for Sufjan Stevens on the Carrie & Lowell tour?

It came two years after constant rejection because people thought my lyrics were too specific. As a Black person, people couldn’t understand if I was rap, R&B, or what. There were all these tightly held opinions which were really exhausting. To find an audience that understood me for me was really special. After my set, I’d be side-stage and just look out into the audience, how they reacted to him just playing guitar, singing very specific, explicit, personal, gut-wrenching lyrics about his life. There were packed auditoriums every night. I was like, “Clearly, this is possible.”

“When I was a kid, I felt like there was a bit of a barrier between me and the world. Making music was the way I expressed myself, culturally. If somebody liked it, it was like they understood me.”

Just the fact that he was open-minded enough to let me come on tour with him was insane. I had no album at the time. He heard a few songs I had on SoundCloud, and that was it. The way he treated me on that tour completely informed how I treat anybody that’s on tour with me. It’s like family, and we want to always make sure people are comfortable and have what they need. I was reminded how welcoming and how open and accommodating and above-and-beyond this person is. I connected it directly to how comfortable he is with making the music that he wants to make, and then being able to sell out tours whenever he wants. His is the paradigm that I want to exist in. It can be done. He’s doing it. I might have other challenges that come with other things, but if I can break through and stay true, then maybe I can get to this level of being comfortable in my own existence and on my own path.

Is there a philosophy that runs through the record?

There are a lot of healing wounds. That’s why I love the title Zinc. It took me forever to find a title, and I use a lot of mood boards to help with these ideas. I knew I wanted something chemical and biological, because there are broken bones. There was almost a Knickerbocker [Hospital] era sensibility of things that are metallic and painful, so maybe the pain is self-inflicted.

It’s an album of healing pain self-caused and caused by others.

Yes, physically, but also molecularly and on an atomic level. FL