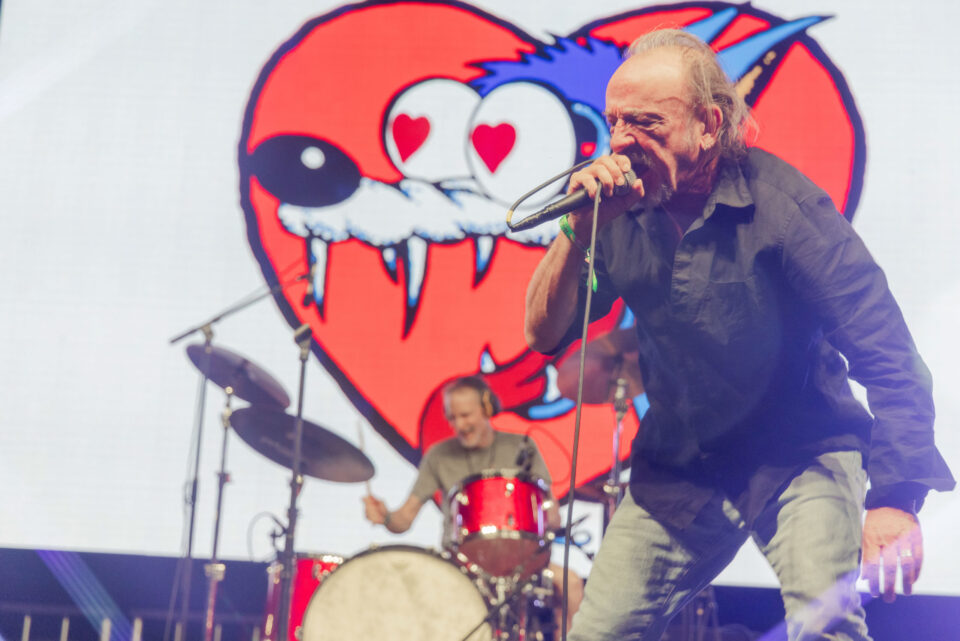

No chronicle of noise rock is complete without a hearty chapter devoted to The Jesus Lizard. Rising from the ashes of vocalist David Yow and bassist David Sims’ immortal Austin project Scratch Acid, the Lizard grew their legs by transplanting to Chicago’s independent music scene. Thanks to the added genius of guitarist Duane Denison and drummer Mac McNeilly, the quartet issued a split 7-inch with Nirvana in 1993 only to later draw the wrath of critical collaborator and recently departed studio legend Steve Albini by signing to Capitol Records two years later. Their mid-afternoon slot at Lollapalooza 1995 was only surpassed in surreality by an opening gig for labelmates Rage Against the Machine the following year. Yow confessed to SPIN that he was familiar with Jeff Beck but not the radio chart-topper Beck, then wondered aloud in a conversation with Iggy Pop for Rolling Stone why the magazine had paired the two together for an interview.

As un-photogenic and raw as any band ever was, The Jesus Lizard were a true singularity: Castigated by Albini as sell-outs, they never stood a chance in a music industry obsessed with trying to find the next grunge scene. Their songs were immaculately ugly, with Denison’s guitar acumen always offset by the nudity-obsessed Yow’s nasty bellowing, screeching, belching, farting, and hollering. During the years when Pearl Jam and Soundgarden seemed to never vacate the charts, The Jesus Lizard were always there for the taking by indie-curious music fans hooked on the raw sound of Nirvana’s decidedly anti-commercial recordings with Albini. Picking the B-side scabs of the 30-year-old In Utero exposed the rugged Jesus Lizard to the cold air of mainstream rock before the fun machine took a shit and died at the turn of the century.

Indeed, The Jesus Lizard never made it out of the 1990s, with their last recordings making the band even more of an oddity. Over time, their first four studio albums released through Touch and Go Records became must-have cassettes, while their last recordings—1998’s Blue on Capitol and a self-titled EP on indie label JetSet—were perceived as head-scratching experiments. What had been a movement became solidified as a memory at the Touch and Go Records 25th anniversary block party in September 2006. Scratch Acid and Albini’s Big Black gave unforgettable performances that no one saw coming—only to be outdone this year by the shocking announcements of Albini’s sudden death in the spring and the Lizard’s first studio album in more than a quarter-century, Rack, which arrived last month via Ipecac.

Indeed, our hour-long conversation with Yow and Denison shortly after Albini’s passing was so dense that we didn’t even have time to discuss their tumultuous relationship with the engineer of their increasingly relevant noise-rock recordings. That said, here are the top lines from our unforgettable talk with the pair.

How are your shows going so far? Your three-encore, 26-song show at Crystal Ballroom in Portland six years ago was one of the most epic concerts I’ve ever attended.

David: We played Nashville the other night. I wish it had gotten more out of hand. It was a small club, and the stage was really high. Then we played the No Values festival, which was poorly organized but fun; and the Garden Amphitheatre in Garden Groves [California], which was a blast. I hadn’t wanted to go to Orange County, especially because the venue hosts Eric Clapton and Bon Jovi tribute bands. And then we did it, and it was fucking magical. I will play that place anytime.

With you guys doing a handful of shows every few years, did you get to the point where you needed new songs to keep your interest level high enough—or did you make it more for the sake of the fans?

Duane: I'm always wanting to play new stuff. There's some songs we've played too many times, I feel like. We started demoing material and, the next thing you know, we had a nice little collection of songs.

David, how did you feel about the proposal to make new songs?

David: I don't remember exactly how it came about. I think we were in a hotel room doing whatever reenactment shows we were doing, and someone said, “Um, let’s make a record.”

Duane: In the old days, we would give songs some road time before recording them. None of these new songs got to have any road time—except we did play “Hide & Seek” at those warm-up shows.

When I saw you in Portland, David, I heard you mutter under your breath at one point, “We’re the fucking best band ever.” Is that what compels you to keep going with reunion shows and now a new album?

David: I don't remember saying that, but I like the sound of it. That's a lot better than John [Lennon] going, “We’re more popular than Jesus.”

Duane: You’ve done that several times. You just did it at the Garden Amphitheater.

“I think the record has the rawness and direct simplicity and spaciousness of our Touch and Go albums, but with the focus, clarity and higher-end of the first Capitol album. It’s a little more full, there’s a little more low end.” — Duane Denison

Duane, I remember you telling me after you finished the second Tomahawk record that there was “no chance in hell” for a Jesus Lizard reunion. Were you working on Tomahawk material before Rack came about?

Duane: No, a Jesus Lizard reunion was the furthest thing from anyone’s mind at that point. When we got back together for the first time in 2009 we still sounded good—maybe even better than we did before, because people weren’t as fucked up. The possibility of new material probably first came up back then. Something I liked hearing people say was, “Wow, I knew you guys would be good, but I didn’t think you’d be that good. Which is an underhanded compliment, but the feedback [about Rack] has been really good. I’d be remiss to say it’s a “green” record, but it’s right up there.

It is, it hearkens back to Head. Were you going for the dingy sound of your earliest material? Your last couple of records on Capitol were so bright and clean production-wise.

Duane: I don't think we were consciously aiming at anything. I think we just started working on the songs and we would listen to the demos. We’d go in and play them live in a really nice, big rehearsal studio. And then [producer] Paul Allen brought a mobile unit, and we recorded it as we went. I think the record has the rawness and direct simplicity and spaciousness of our Touch and Go albums, but with the focus, clarity and higher-end of the first Capitol album [1996’s Shot] that GGGarth [Richardson] did. It’s a little more full, there’s a little more low end. We didn't, as a band, necessarily have any production ideas of how we should sound other than what we sound like when we're playing.

David: Before we started recording, Paul asked me to make a list of 15 songs—whether they were by The Jesus Lizard or Scratch Acid—and he used that as a base for recording the vocals. When you're a singer and you're not necessarily good at singing, it's rough to hear yourself sometimes. But I think my voice sounds really cool on this record. I don't really know exactly what it is, whether it's an [equalization] thing or a fact or whatever. But to me, I don't cringe when I hear it—and I have done a lot of cringing hearing myself in the past.

“A larger percentage of the lyrics than I wished were based on the political climate in the US. I think they’re some of the best lyrics I’ve ever written, because what’s going on is so stupidly disgusting and equally hilarious.” — David Yow

You hit a higher octave than in the past, especially on “Falling Down”—which seems unusual as a band gets older.

Duane: Yeah, David's singing high pretty consistently on this album.

Were you concerned with the new songs taxing on your voice playing them live? I wouldn’t recommend seeing Guns N’ Roses nowadays for that very reason.

David: He’s singing for AC/DC now? What in the actual fuck?

Duane, going back to the second Tomahawk record, the word you used to describe it was “expansive.” Was that a priority with Rack as well?

Duane: There’s a good balance. Some of the stuff is fairly busy, like “Hide & Seek,” but the second single, “Alexis Feels Sick,” is fairly sparse. “Armistice Day” is sort of slow and long—but then from the song after that, “Grind,” ’til the end, it’s just banging from start to finish. I can’t listen to something that’s constantly hammering me and overwhelming me with beats and riffs and screaming and howling. I need some sparseness in there. Your imagination starts filling in things, and next thing you know, your mind is wandering off, and you’re thinking about I Love Lucy or something. You know?

David: I do and I don’t. Where’s she been?

David, we’ve been waiting 27 years for your commentary on Y2K and Ross Perot’s candidacy. Did you pull material from journals?

David: I did “automatic writing,” where I gave myself eight or 10 minutes to write without stopping. A larger percentage of the lyrics than I wished were based on the political climate in the US from the last seven or eight years. I think they’re some of the best lyrics I’ve ever written, because what’s going on is so stupidly disgusting and equally hilarious. “I’ve given golden showers / To folks who’ve been dead for hours.” I’m really proud of that.

Are you surprised by how coarse the culture's gotten?

Duane: Yes!

David: The level of discourse keeps dropping.

“I think my voice sounds really cool on this record. I don’t cringe when I hear it—and I have done a lot of cringing hearing myself in the past.” — David Yow

Duane: It may be because the education system keeps getting defunded. And then you've got the internet, where everyone's a “writer.” Everyone's in a big hurry to say something. So they don't bother checking their spelling or punctuation or grammar or anything else.

David: When I read about how military training manuals are being written at a fourth grade level because the [kids] can't understand anything else, it’s just saddening to me. We went through a period where anything intellectual was mocked. If you're intelligent, you're probably a homosexual. This would be an amazing time to be a linguist. Language is evolving—or devolving—so fast. Unsafe clothing and things you would’ve been arrested for 50 years ago are all over the place.

I wonder if you started the band now, if you’d have turned out much different. Too many of the stories written about you revolved around the indie label versus major label debate.

Duane: It shouldn’t have been an issue in the first place. Criticizing people for, say, signing a contract with a larger company…that is the most elitist, gatekeeper mentality. It's coming from a position of privilege, isn't it?

David: It’s people trying to move up in the world. “I don’t agree with that, that violates my imaginary code of ethics.”

Duane: It was a bunch of privileged, entitled idiots. Now, here we are 30 years later, and record stores don’t even exist anymore. Nobody cares, younger people today. I have a teenage daughter, and they don't care what label the music they listen to is on. To think these gatekeepers were making such a deal of it just shows how ridiculous and out of touch they were. And maybe some of them still are.

David: I’m waiting for 8-tracks to come back. FL

The Jesus Lizard