All you need to hear is one coordinated shriek from Jordan Blilie and Johnny Whitney to know that there’s no one else like The Blood Brothers—and that there’s never going to be anyone like them again. With whiny falsettos and throat-shredding screams, and lyricism revoltingly unflinching and deceptively complex, the Washington post-hardcore band made an unshakeable impact in just 10 short years of initial activity between 1997 and 2007.

As soon as I got a taste of Blood Brothers’ sound, I couldn’t get enough of it. I remember being blown away on my first listen of the band’s 2003 Ross Robinson–produced Burn, Piano Island, Burn—Blilie and Whitney’s interplay was so fearless, so flamboyant, and so humblingly obnoxious that their sheer bravado and range of projection was downright hypnotizing. And that’s barely even broaching the surface of Cody Votalato’s frenetic guitar work, Mark Gajadhar’s feverish rhythmic intensity, or Morgan Henderson’s emphatic basslines.

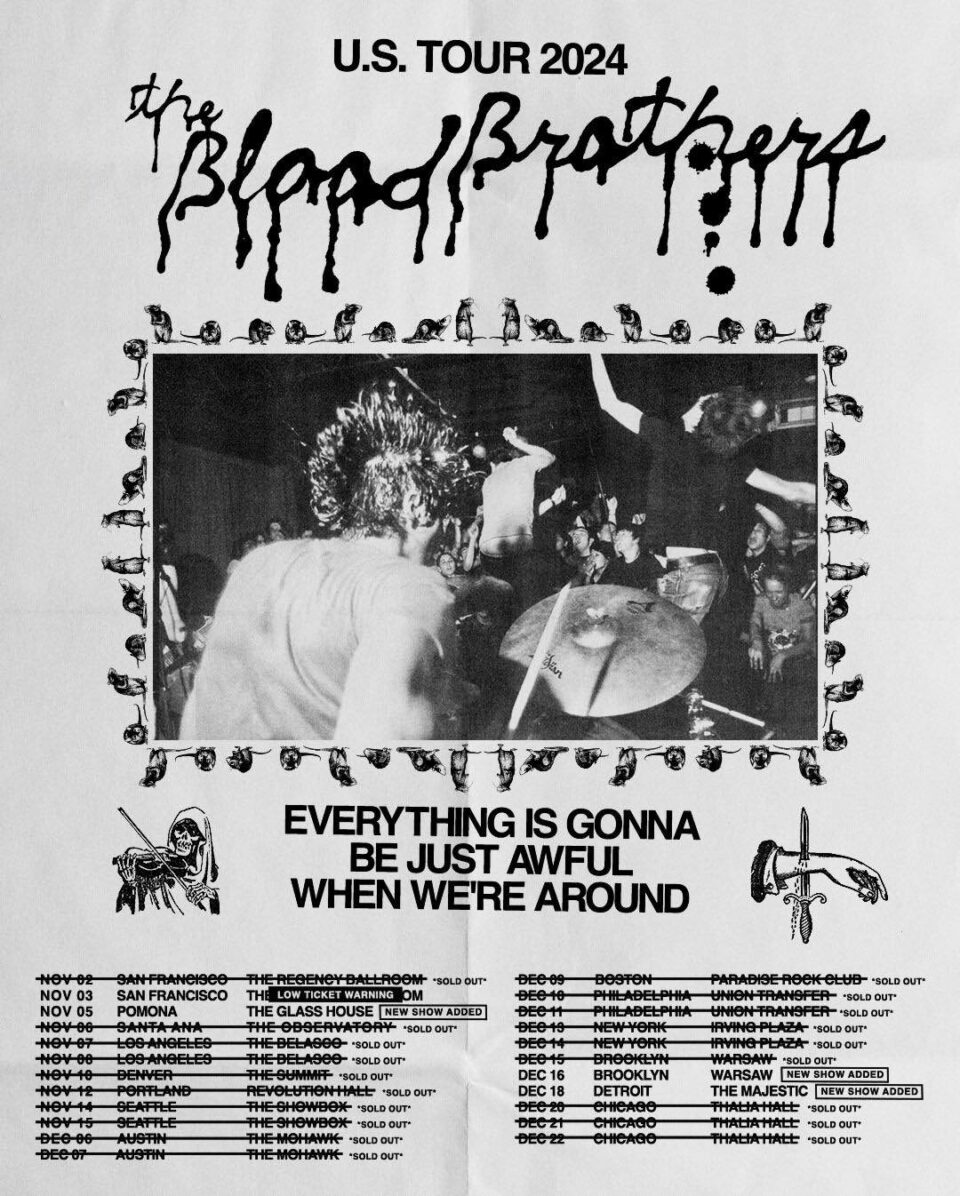

Released just one year later, Crimes takes all the madness and ambition of its predecessor and filters it through as many modes of operation as possible for the band. As that fourth album turns 20 this week, the band are reissuing the record and will begin their first set of live dates in a decade next month. Whitney and Blilie sat down with us before the tour to speak about coming back to these songs in a new era, the band’s legacy, and the differences between the 2000s hardcore scene and today’s.

What’s it like for you coming back to these songs a decade after the last time you toured?

Jordan Blilie: I just get reminded, when the five of us are together, of the sense of deep comfort you have when you get to be in a room with people you’ve known for the majority of your life. I’m incredibly grateful that the entire band was excited to get together again. I feel incredibly grateful that people are excited to see us. It does kind of mess with your sense of time when you look at the fact that we’re playing stuff that we wrote 20 years ago. Personally, I don’t feel old, yet to my twentysomething self, I’m about as old and uncool as I could possibly be.

Johnny Whitney: It also feels like muscle memory. The fact that we toured for so fucking long—like six to nine months—for years. There’s something in my neural network that will never go away for performing some of those songs.

I think a lot about how relevant a lot of the more pointed stuff you recorded is, especially Crimes.

Whitney: It’s interesting, some of the things that felt hyperbolic in the lyrics when we wrote them don’t feel that way now. It feels like the world has sort of manifested itself into some of the things we talked about that seemed ridiculous at the time.

Blilie: With Crimes in particular, we were mining the worst of human impulse. We live in this point in time where, for the past decade or so, you just see that day-in and day-out anytime you pick up your phone.

Whitney: Especially a song like “Devastator.” I feel like I could’ve written that now about Gaza. It was about the Iraq War, but the images of what the declining empire has wrought over the past 20 years are more in-your-face now.

“I get reminded, when the five of us are together, of the sense of deep comfort you have when you get to be in a room with people you’ve known for the majority of your life.” — Jordan Blilie

In a 2014 interview you brought up the fact that recording anything new this far away from the original records is going to be a different perspective altogether. Do you feel like that’s still true?

Blilie: It’s a really difficult endeavor to pull off, and I’ve always been really hesitant about it. In my mind, the examples of artists that are able to come back after a long hiatus to create something that feels fresh and relevant and powerful are pretty few and far between. More often than not, it’s very difficult to recapture that very specific chemistry and magic.

Whitney: Specifically if you start a new band after. We both started [new bands] after we broke up. There’s a magic between the five of us that was immediate to everybody. When we were teenagers and started the band, we were all in other emo bands that we took very fucking seriously. We started The Blood Brothers as a way to do something fun that wasn’t a fucking thesis. People picked up on that right away. Our shows started to get bigger than the things we considered our main bands.

I would disagree with you a little bit, Jordan. I feel like we could come back and do more music, because that connection is still there, given the right set of circumstances. I’ve been bottling up creative energy from the past 10 years of doing nothing. But the thing that would be the biggest impediment is just that the reality of doing that is very stark. I have four kids, Jordan has two kids. It’s fucking hard as hell to make money as a musician. You have to be fucking insane to do this, or just give up any prospect of not being on food stamps.

It’s tricky, because you have to contend with people comparing the new stuff to what came before without just recycling the same sounds.

Whitney: I feel like Young Machetes was our best record, but it was so excruciating to make, and after that, we were at this inflection point where we all went off in different directions and tried to explore different sounds. Aligning on a way to actually make songs out of that was pretty tough. It would go into a direction that strayed too far from what was special about our band. If we did another record, I always pictured that it would be like Combat Rock. I personally like it—there’s two fucking awesome songs, but it doesn’t sound like The Clash.

Blilie: You ever play Oregon Trail? You know how you can set it to “meager rations, grueling pace”? And then just see how fast it takes for you to run your oxcart into a ditch? I felt like we were on “meager rations, grueling pace” for a number of years. If we weren’t on tour, we were writing and recording. By the time we got to Young Machetes, we were running on fumes. But I do have really fond memories of recording that. I was really thankful that we were able to keep it together long enough to have that experience. But you just can’t keep that pace. At some point, the wheels fall off.

Jordan recently described Crimes as both “feral and weirdly focused.” How do you feel it fits between the erraticism of Burn and the variety of Young Machetes?

Blilie: Burn felt like expanding: The songs got longer, they got more complex. We were putting more parts on top of one another. Crimes felt a bit more like we were contracting, but to me, it was a very freeing record to write. We were at a place where there was something really healthy going on with the chemistry and what we were each bringing that was making it very productive and easy. The songs became a bit simpler—and I think better—for it.

Whitney: The thing that I think is important to remember is that there was a non-zero amount of risk to what we did on Crimes. This is so different from anything we’ve done in this band before. There’s a possibility that a lot of people are going to fucking hate this. Crimes is the most we sold of any record. When we came to Young Machetes, there was less of that feeling of having the scythe over our heads as we were trying to experiment, because we already proved we could do it. We felt the confidence in being a band that could be in with this very chaotic, hardcore genre of music, but also something that nobody else was bringing to the table. One thing that was not apparent to anyone that wasn’t in the room when we were doing Crimes was that we were putting ourselves at risk and going out on a limb.

“We started The Blood Brothers as a way to do something fun that wasn’t a fucking thesis. People picked up on that right away.” — Johnny Whitney

I’m curious to hear about your impulses for self-referentialism. “Piano Island” as a concept keeps coming up in your music, and phrases like “talk out of tune” and “Siamese gun” both recur across your work.

Whitney: None of our songs are really about anything—it’s more about painting a picture or describing an image. It just tickled a part of my brain. For “Burn, Piano Island, Burn,” it was like an everything-bagel of Blood Brothers song lyrics: it’s fucked up, it’s disturbing, it’s creative, it’s funny, it doesn’t take itself too seriously.

Blilie: I always love artists that repeat certain ideas or characters or scenes. You’d see that a lot with Bowie—there’d be little threads woven through. I like the idea of creating a little world, and that’s how I’d always ingest and process lyrics that Johnny would hand me. Sometimes they’d have this little leftover piece from something else we’d done. I liked the pure audacity of having that first major-label record title be self-referential to something that only a few hundred people had heard before. I think a lot of it, too, is that we’d always have fun finding ways to make each other laugh. Those were my favorite moments in creating with Johnny.

Whitney: One of the things that was different about our dynamic is that we did edit each other. I’ve known Jordan since I was fucking 12 years old. I feel more comfortable giving you feedback than some other people in the band, because we’re part of it, but we’re not making the actual music. Not having Jordan as somebody who critiqued what I was doing definitely made my lyrics worse when we weren’t in this band. I can be the best version of myself when my ideas are restricted by other people’s ideas. Not all your ideas are always great.

Blilie: I know mine aren’t [laughs].

There was occasionally some pushback from the more macho portions of your scene. How have you sensed the climate has changed there?

Whitney: If you were a hardcore band that was breaking into the mainstream, we were like the Andy Kaufman to their Jerry Seinfeld or whatever. We were the band that all the really popular bands liked, so we got a lot of offers to go on tour with them. We just weren’t palatable to that kind of audience. A lot of people really fucking hated us. There’s kind of a feminine energy to what we do, and 2024 is a very different place. There’s much more acceptance of bringing that kind of energy to the table.

Blilie: What would also happen was that the people that did connect with what we were doing connected on a very deep level. I always liked bands that were a little weird or off-kilter. You didn’t quite understand them, or they ignited something in your imagination. But I remember lots of times playing festivals that felt more hardcore-leaning, and it gave me flashbacks to high school—we’d always eat lunch down in some weird corner of the hallway.

“The idea of a band with two singers that are skinny, femmy dudes was disgusting to a lot of mainstream audiences seeing AFI.” — Johnny Whitney

The thing that made me think about this evolution over time is seeing how many active bands with queer and trans people take influence from Blood Brothers.

Whitney: The worst thing anyone ever screamed at me was, “Shoot yourself in the head, you fucking [F-slur redacted by Whitney].” At the same show, somebody threw their shoes at us, which, like…how are you going to walk out of the club?

Blilie: I remember a full, Big Gulp–sized Pepsi [being thrown at us].

Whitney: We opened for Metallica in Portugal on this festival tour and I was being catcalled because people thought I was a girl. And then as soon as I spoke, everybody realized I was a man and it was a fucking wave of screaming and booing.

Blilie: They weren’t booing me. They liked what I was doing.

Whitney: I don’t think anybody would do that anymore. That’s no longer something that’s a cultural norm. Just the idea of a band with two singers that are skinny, femmy dudes was disgusting to a lot of mainstream audiences seeing AFI.

Blilie: It’s a very different world now, and I think it’s a much better one, as far as those things are concerned. At least from the bands that we’re playing with on this upcoming tour, we’re seeing much greater diversity than what I remember from when we were a band in the early 2000s. FL