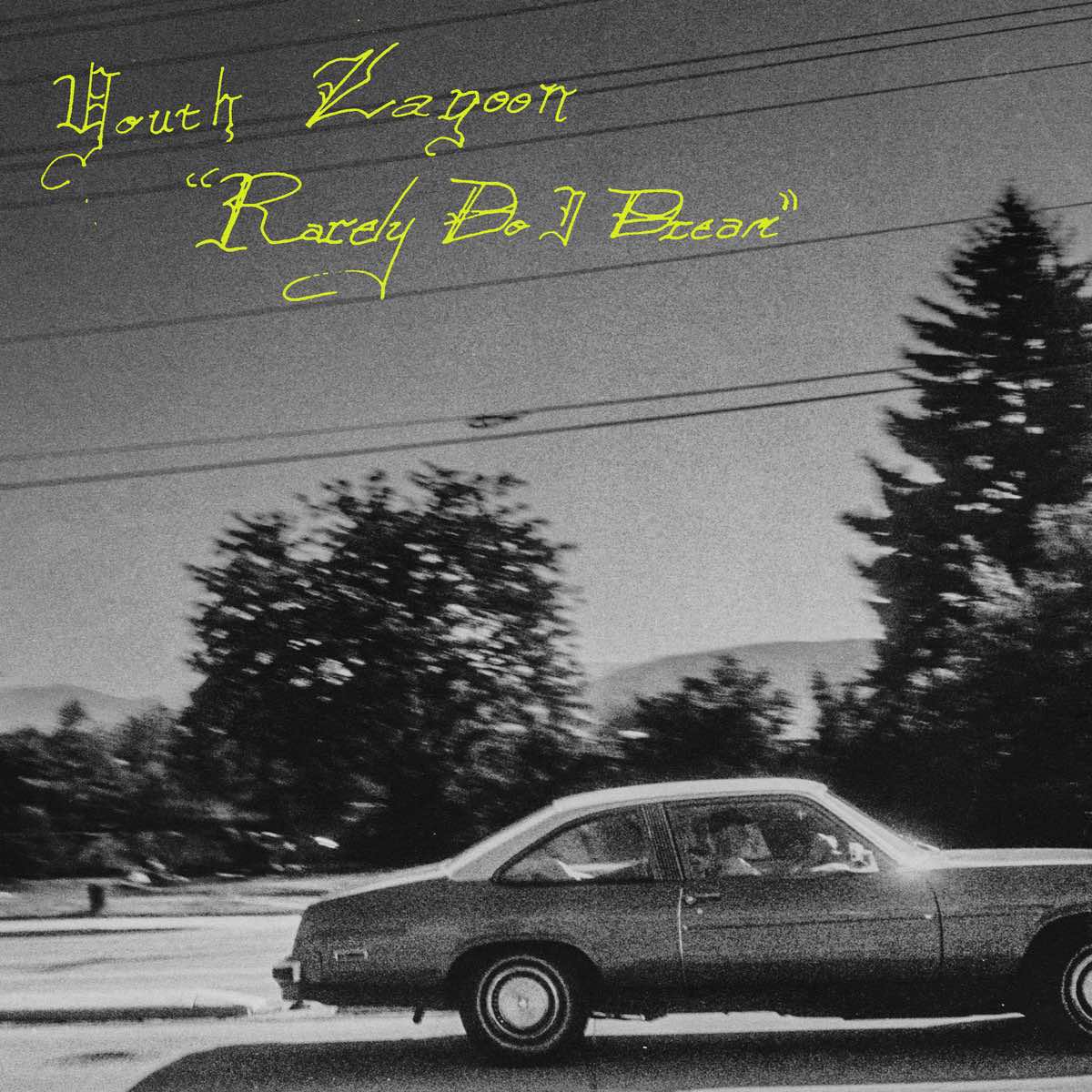

Youth Lagoon

Rarely Do I Dream

FAT POSSUM

“No one wants to hear what you dreamt about, unless you dreamt about them.” These are particularly wise words from Built to Spill’s Doug Martsch. No matter how enlightening, disquieting, bizarre, or Freudian the dream may be, there’s simply no way it could matter as much to someone else as it does to you. I think the same can be said of home movies. Have you ever tried showing someone a video of you running around the backyard at your brother’s third birthday party? Watch as their eyes glaze over and their voice rises to the octave of indulgence. See how far you make it into the six-hour shaky-cam footage your father was kind enough to transfer to DVD a decade ago.

Herein lies the fatal flaw of songwriter Trevor Powers’ latest release as Youth Lagoon, Rarely Do I Dream, a record that weaves the audio from hours upon hours of family home movies into the foundation of nearly every song. For Powers, these bits of autobiographical data may be revelatory, therapeutic, and inspiring, but for us, all they do is create a layer of remove, remaining merely fragments of a story half told, with very little to glue them together. I don’t mean to be harsh—it’s not as if Powers doesn’t aim to blend the context and content of his inspiration. As the title suggests, album opener “Neighborhood Scene” is all about scene-setting, inviting us into Powers’ Idaho childhood by way of a local fair and a friend’s dad’s possible infidelity. From there the album takes a decidedly proper-noun approach to storytelling: Donnie, Mary, Jack, Lucy, and Josie all make appearances right beside Powers’ immediate family, who pop up on nearly every track.

Powers has called the conceit an attempt at a sort of hyperreality. The lyrics often reflect the kind of moral rot we’ve seen before from stories of suburban despondency: speed freaks, sex workers, mystical murder, morphine doses, and pills hidden in the bottom of a sandal all serve to infect Rarely Do I Dream with the seedy underbelly of a modernized Jesus’ Son. Where this might meet Powers’ own biographical record is ultimately unclear. This isn’t an issue on its own—Powers has always been a songwriter unafraid to explore the darker edges of his psyche—but when the concept introduces home movies as its base structure, you can’t help but expect a little more in the way of personal revelation rather than the literary approach taken instead.

Ultimately, what he’s doing from a composition perspective is much more interesting. There was a time, on the heels of his 2015 record Savage Hills Ballroom, when Powers was determined to move on from the Youth Lagoon moniker. Now, as he says in the album’s bio, “my ideas are a river. I can’t keep up.” That impulse is evident not only in his increased output lately, but in the songwriting itself. Powers’ greatest skill has been his control of momentum. Blending psychedelic dream-pop and more restrained balladry, his songs toe the fine line between muted and manic. If they lean too far in either direction, they might fall apart; but as is, Powers is able to use suggestion and absence as key tools in his arsenal.

Even within the context of “Speed Freak,” a harsher, more propulsive single to a largely lighter record, his ghostly warble gives the whole thing a gentle vulnerability even as things spiral out of control. The most effective moments of the record often come when Powers allows them space to breathe. The conclusions of both “Gumshoe (Dracula From Arkansas)” and “Canary” untangle the songs’ tight melodies until they’re almost unrecognizable, an old videotape fraying at the edges. It’s in these moments—far less didactic and pronounced than others—that the record truly shines, even if they’re fewer and farther between than one might hope.