Ah, yes, Awards Season—a time for quantifying and qualitating all of our favorite art forms; for taking an experience as simple as watching a movie and injecting politics, competition, and general unpleasantness into the proceedings. We’re now only days away from the Academy Awards, and even as I acknowledge its many flaws—its frivolous core, its idle vanity, its spotty broadcast—I also cop to being one of the biggest suckers of all.

Perhaps I’m part of a shrinking minority, but every year I allow the Oscars not only to hold my attention on Movies’ Biggest Night, but to greatly affect my movie-watching habits in the months leading up to it (would I have subjected myself to movies I do not care for—and maybe even hate—like Emilia Perez had the Academy, in all their wisdom, not decided to heap praise upon it? Almost certainly not). In anticipation of this Sunday’s very-normal ceremony, I’m sure, we’re taking a deep dive into the creative forces behind some this year’s biggest movies. The Academy Award for Best Directing is, without a doubt, one of the most coveted awards of the night. It’s a chance to place a big, gaudy stamp of approval on a filmmaker that will, no matter the IP-drivel they may take on for their next project, confirm them as an auteur of great and singular importance.

This year, it’s noteworthy that all five of the Best Directing nominees are on the ticket for the first time in their careers, marking the first time in 27 years that this has been the case. Of course, this doesn’t mean this is a slate of wunderkinds—for some of these directors, this represents a topper on a long career; for others, a signifier of newfound opportunity; for each, an honor and chance to solidify their place in film history. Today we look back at the movies that initially made them, and how these titles might better help us understand—even admire—the film’s being honored this Sunday.

SEAN BAKER

It’s been a slow and steady build toward Academy recognition for Sean Baker, a longtime indie darling whose latest film marks a significant jump in notoriety. Anora, his ninth film, continues many of the themes he’s been exploring since his early days working in NYC, fresh out of Tisch School of Arts. Baker is very much an auteur in the classic sense of the word, establishing a house style that he retains even as his budget rises and his scope expands.

Takeout (2004)

I think there are valid questions to ask regarding Baker’s obsession with marginalized, often immigrant communities and his position as arbiter of those stories, but it’s hard to doubt his commitment to arriving as close to the truth as possible. Take Out—the story of a Chinese immigrant and bicycle delivery man’s fight to keep his head above water in an uncaring, cruel NYC—is about as close as you can get to documentary filmmaking while retaining narrative structure. Shot on a digital camera for a reported $3,000, Baker’s verite style is the perfect format for a story wholly unambiguous about the debilitating blur that everyday life can become under late capitalism. Its subject is a man for whom the hustle has become both the means and the end, the grind replacing our collective humanity one delivery at a time

Anora

The two decades between Take Out and Anora saw Baker explore all types of workaday people struggling to maintain even a passing glimpse of the American Dream they’re constantly being sold. In Anora, that dream is presented in Russian, in the form of Mark Eydelshteyn’s certified fuckboy Vanya, who sweeps the titular Anora (Mikey Madison) off her feet and into silk sheets and all-night binges in Vegas. Things go awry from there, and watching Madison slowly sink back into the reality she’d thought she might have escaped is devastating, exhilarating, and anxiety-inducing in equal measure. This is, in my view, the most pure plot we’ve ever gotten out of a Baker feature. There are times when it even threatens to achieve a type of liftoff that doesn’t quite fit Baker’s style, only to come crashing down to a weathered, deeply sad conclusion, once again proving his ability as a filmmaker of injustices both cosmic and everyday.

BRADY CORBET

There is perhaps no director in this field—or in recent memory, for that matter—who is as nakedly in pursuit of the kind of industry approval that the Academy can provide. Having toiled as an actor for years (his debut came on The King of Queens back in 2000 at age 11), Corbet has, over the course of his now three feature films, positioned himself among a new wave of ambitious auteurs.

The Childhood of a Leader (2015)

Some of the directors on this list began as journeymen. Some, in their way, remain so. But for Corbet, his vision—and the techniques he’d use to realize that vision—were there from the very beginning. His directorial debut The Childhood of a Leader is split into chapters, uses archival newsreels as narrative guardrails, features an arresting original score, and displays technical bravado in the form of complicated blocking and extended single-shot sequences. But it’s not just the filmmaking that tethers this movie to its Oscar-nominated successor. Childhood of a Leader is an ardent attempt to place its main character (a young boy growing up in France as his father works to negotiate the Treaty of Versailles) into the hardened context of history, exploring fascism and Freud in equal measure. The effect is a film that unfolds with the heavy hand of metaphor constantly pushing the scales, where no less than the entire history of the world can be grafted onto a little boy, his complicated relationship with his mother, and the question of where and when evil is born.

The Brutalist

I don’t mean to paint Corbet’s obvious ambition in a negative light, but you simply cannot release a nearly four-hour epic shot on 35mm film stock—which includes a 15-minute intermission—without earning a few eye-rolls. Who does this guy think he is? He hopes, I think, to be no less than Coppola, Scorsese, and PTA wrapped into one, and you know what? For at least some of The Brutalist, he seems capable of reaching such lofty ambitions. Both his first feature and his second, 2018’s Vox Lux, are grand visions, but this is the first time that the massive, tectonic plates Corbet wishes to shift in hopes of making the Great American Movie service of something approaching the worthiness he’s constantly insisting upon. Sure, his characters at times remain broad and drenched in metaphor (Felicity Jones as Erzsébet Tóth to bad effect, Guy Pearce as Harrison Lee Van Buren to good), but this is the first time Corbet’s film has worked as both an intriguing thought experiment and an engaging movie. It sounds crazy to say that 202 minutes feels like the perfect run time, but perhaps that’s the ideal way for Corbet’s earnest blueprint to truly come to life.

JAMES MANGOLD

If it can be said that Corbet, in his own way, has been working on one single film his whole career, Mangold represents the kind of director intent on servicing the story and its characters above all else. Whether this means eulogizing one of mankind's most important costume-wearers (Logan) or helping Tom Cruise produce a romcom wherein his character’s life is still in danger (Knight and Day), Mangold is one of the most reliable Hollywood hands of the last 30 years, one whose Oscar nomination certainly feels overdue.

Cop Land (1997) / Girl, Interrupted (1999)

During a recent interview on Marc Maron’s WTF Podcast, Mangold called plot “the enemy of lyricism.” This is, perhaps, something he learned on the set of Cop Land, a movie whose lyricism is suffocated under a mountain of plot. But despite the film’s faults, its very existence is impressive and particularly mind-boggling to consider in 2025. In 1997, Mangold had made exactly one low-budget feature film, and yet was handed a $15 million budget to write and direct a movie starring Sly Stallone, Robert DeNiro, Harvey Keitel, and Ray Liotta. The film has many flaws, but the performances are not among them, a sign of things to come for the young director.

Though this year marks Mangold’s first Best Directing nomination, it should be noted that he’s far from a complete unknown within the Academy—it just hasn’t been him getting the recognition for his projects. Including this year’s slate, Mangold has directed six actors to Academy Award nominations. This started back in 1999 with Girl, Interrupted and the force of nature that was Angelina Jolie’s Oscar-winning performance as Lisa, a sociopath with a heart of acid who runs away with the movie a half dozen times before returning in a straightjacket. Hers isn’t the only winning performance, as the incredibly talented roster of young actresses (Brittany Murphy, Elizabeth Moss, Clea DuVall, Winona Ryder) largely keeps an uneven script from hemming too far into melodrama.

A Complete Unknown

In many ways, working with Ryder in the late ’90s must have been a lot like working with Timothée Chalamet in 2024. After Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands had made her a darling of Hollywood, Best Supporting Actress nods for The Age of Innocence in 1994 and Best Actress in 1995 for Little Women had solidified her as one of the premiere stars of the moment. Similarly, the many years preceding A Complete Unknown saw Chalamet go from up-and-comer to candidate for Mayor of Hollywood. A Complete Unknown is a masterfully done music biopic, but more than anything else, it’s a star showcase for not only its lead, but the acolytes, collaborators, and lovers that live in its subject’s orbit. Mangold isn’t particularly showy in this or any other movie, but hell if he doesn’t know where to place both the camera and his trust. Did he know what he had with Monica Barbaro? Was he aware Chalamet could pull this off? Whether he was certain or not, he gave them the opportunity, and they nailed it.

JACQUES AUDIARD

Jacques Audiard, one of two French filmmakers to be nominated this year, is easily the most difficult to wrap my head around. A screenwriter, producer, and director for over 30 years, Audiard has made everything from gritty crime films to romantic melodramas to whatever it is Emilia Perez is attempting to be. Like Baker, Audiard almost always centers his stories around marginalized individuals trapped within larger, uncaring, often violent systems. His stories can be riveting, his characters complex—but there remains a nagging question of what Audiard has to say about any of it, one that rears its head this year more than ever.

A Prophet (2009)

“Of course it has no message… In my film, I wanted to make a nice guy just like you and me, who also kills.” This is from an interview Audiard did with Huffington Post around the release of A Prophet, and it goes a long way in explaining Audiard as a filmmaker. There’s a lot going on in A Prophet, from the incredible lead performances of Tahar Rahim and Niels Arestrup, to the fascinating cat-and-mouse game between rival prison gangs, to a murderer’s row of moral quandaries. And yet any time the film threatens to delve a little deeper, to really consider the actions of its hero, to ride the razor’s edge between opportunism and amoralism, to unpack issues of identity, sexuality, and violence, it retreats, slowly but surely, to safer ground. Because, but of course, it has no message.

Emilia Perez

Be careful what you wish for, buddy, because here comes Emilia Perez, the movie that definitely has a message. Or, that’s what Academy voters seem to think, because, once again, for the life of me, I cannot decipher what this movie is trying to say. Ostensibly a story of a cartel kingpin’s gender transition and subsequent life as do-gooder attempting to atone for past sins, Emilia Perez tries desperately to create the infrastructure for moral dilemma, asking big questions in place of narrative tension yet revealing almost nothing about the characters at its center. That isn’t an issue in and of itself. For all my talk, movies don’t have to mean anything, but when a film is so patently absurd and yet so clearly as enamored with itself as Emilia Perez is, you kind of wish it gave you something to hold onto.

CORALIE FARGEAT

Unlike Audiard, Fargeat is a director for whom the message lives in bold, garish typeface—to hell with subtext. Fargeat separates herself from her competitors in a few ways, some of them obvious, but most fascinating is her place as a pure genre storyteller. The Substance is only her second proper film, but if you include her 2014 short film Reality+, Fargeat has clearly established the kinds of stories she wants to tell and how she plans to tell them.

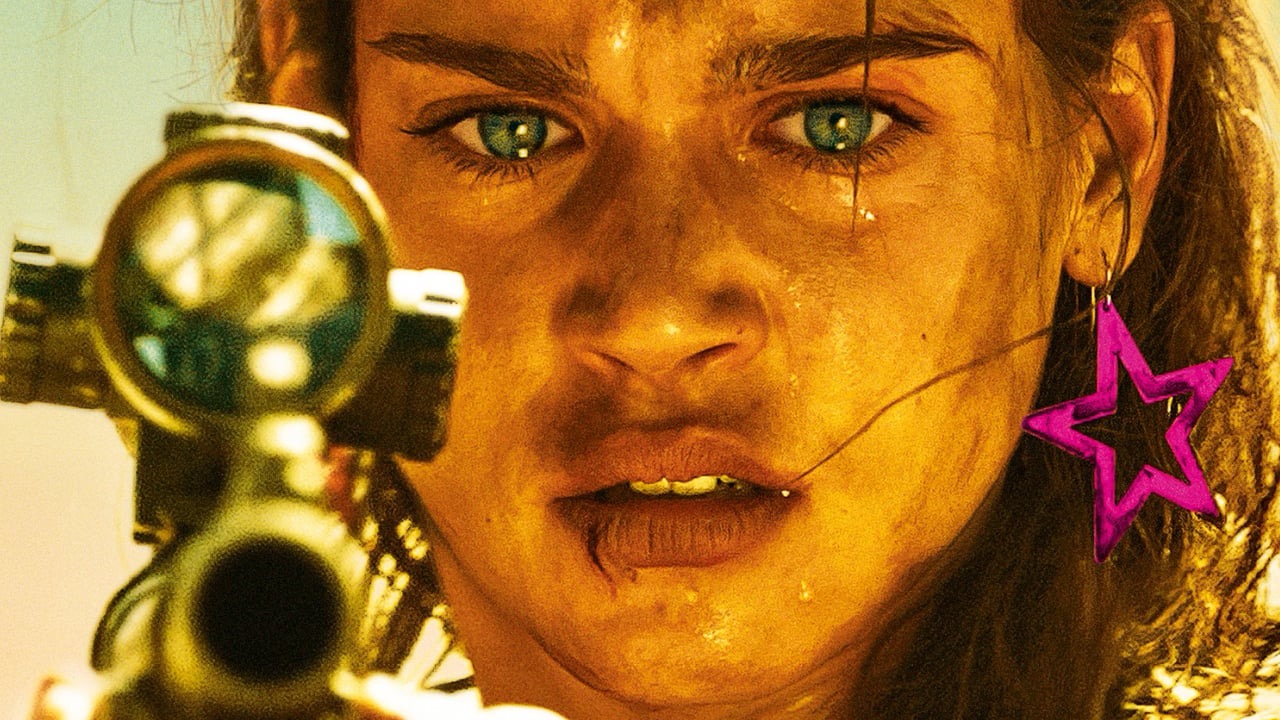

Revenge (2017)

2025 marks just the tenth time in Oscar history that a woman has been nominated for Best Directing, and though I don’t wish to frame everything about Fargeat’s films around this fact, it is hard to deny gender’s place within her storytelling. On its surface, Revenge is an updated entry into the rape-revenge canon, extreme and graphic in its depiction of well-earned comeuppance. Much like its successor, it’s also presented through the prism of a world of such hyperreality that the action feels more fever-dream than gritty-reality. From its themes to its imagery to its stark color palette, everything about it is audacious (if I had a nickel for every phallic stand-in). But it works not despite its obviousness but because of it, willing to shove lust, commercialism, and toxicity in your face with refreshing confidence.

The Substance

It remains pretty baffling that a film like The Substance—one that implements hard sci-fi, body horror, and buckets upon buckets of bodily fluid—not only earned Academy attention but made a significant cultural impact in a time when movies that are this out-there often come and go with little notice. Part of that is due to the performances and star power of its two leads, Margaret Qualley and Demi Moore, but just as much can once again be attributed to Fargeat’s willingness to follow her story all the way to its visceral conclusion. Image, sexuality, and feminism are all once again in Fargeat’s crosshairs, and while some of the conclusions she makes here may feel harshly lit, they never feel half-hearted.