When Nine Inch Nails unleashed their sophomore album The Downward Spiral in 1994, they turned the music world on its head. The profound concept album spanned industrial angst to ambient sorrow as its emotionally wounded protagonist descended into depression, self-harm, and madness. It also delved into toxic masculinity before that term became part of our cultural lexicon. Both the album and its ensuing tour became an iconic moment in alt-rock history.

Through a serendipitous connection with NIN mastermind Trent Reznor, Jonathan Rach became the band’s tour photographer for that cycle, and the cinematographer/director of the live and behind-the-scenes footage for the 1997 film Closure. He captured the mayhem on- and offstage during the group’s two-year “Self Destruct” world tour. Rach recently showcased his photos from that era in NYC (“Nine Inch Nails, The Downward Spiral”), and that exhibit is coming to a Los Angeles gallery at 7615 Sunset Boulevard between March 6 and 9. More info on that here.

We recently spoke to Rach at the Morrison Hotel Gallery in NYC about the touring exhibit, as well as about that exciting and turbulent time in NIN’s career that his photos document.

You met Trent during the Downward Spiral sessions. Did you go to the Sharon Tate house while he recorded there?

I didn’t. I met him because they kicked him out of the house. He was renting the Sharon Tate house, and somebody bought it and wanted to tear it down. He wasn’t quite done mixing the album, so they moved into a [studio] building that I was at, and that’s how I met him. I did his stage design. That was the first thing I did, I came up with the concept.

Did you study set design in school?

I didn’t. I was working at the studio, and I submitted a stage design and he liked it. I didn’t have the skillset to bring it to life, so they used a guy by the name of Roy Bennett, but it was my sketch that they used. It was a trip—I was like, “I’m gonna be a stage design guy,” because I’m getting this big break. Then before that week was out, Trent asked me if I wanted to do a documentary—come out on the road and be a fly on the wall. Talk about an offer, that was crazy.

“I’m living with the subject. I’m with the band, so I was trying to capture what I was experiencing, the emotions of it all. It was just a very privileged situation.”

It sounds like trust was a big part of the decision.

Yes. “Do you fit in? Does the band like you?” You have to live with each other for months, so a big part of that is if our personalities are going to work together.

You hadn’t done a lot of photography before then. What was it like in the beginning?

The first place I went to buy [a camera], I was on the tour already. And Anton Corbijn said, “You’re here, so why don’t you pick up a camera?” I took his advice, and I literally went into a tourist shop in Hawaii to buy my camera. Of course, I was sold some shitty tourist camera that I couldn’t handle, and I was slowly learning my lessons as I was going.

Some of the photos are very raw—soft focus with a low exposure—whereas some are sharp as a tack. Was there anything you were going for, or was it done just on the fly?

Because I wasn’t training, I didn’t have a head full of technical things. The truth of the matter is I had a lot of opportunity. Most photographers don’t get that opportunity. They only get the first three songs [today]. I was getting every song of every show. But not having been trained, I didn’t know anything other than just to emotionally fill it out. If it felt right I would take the photo. I’m living with the subject. I’m with the band, so I was trying to capture what I was experiencing, the emotions of it all. It was just a very privileged situation.

Trent seemed both purposely and unintentionally chaotic on the tour. How did you cope with that?

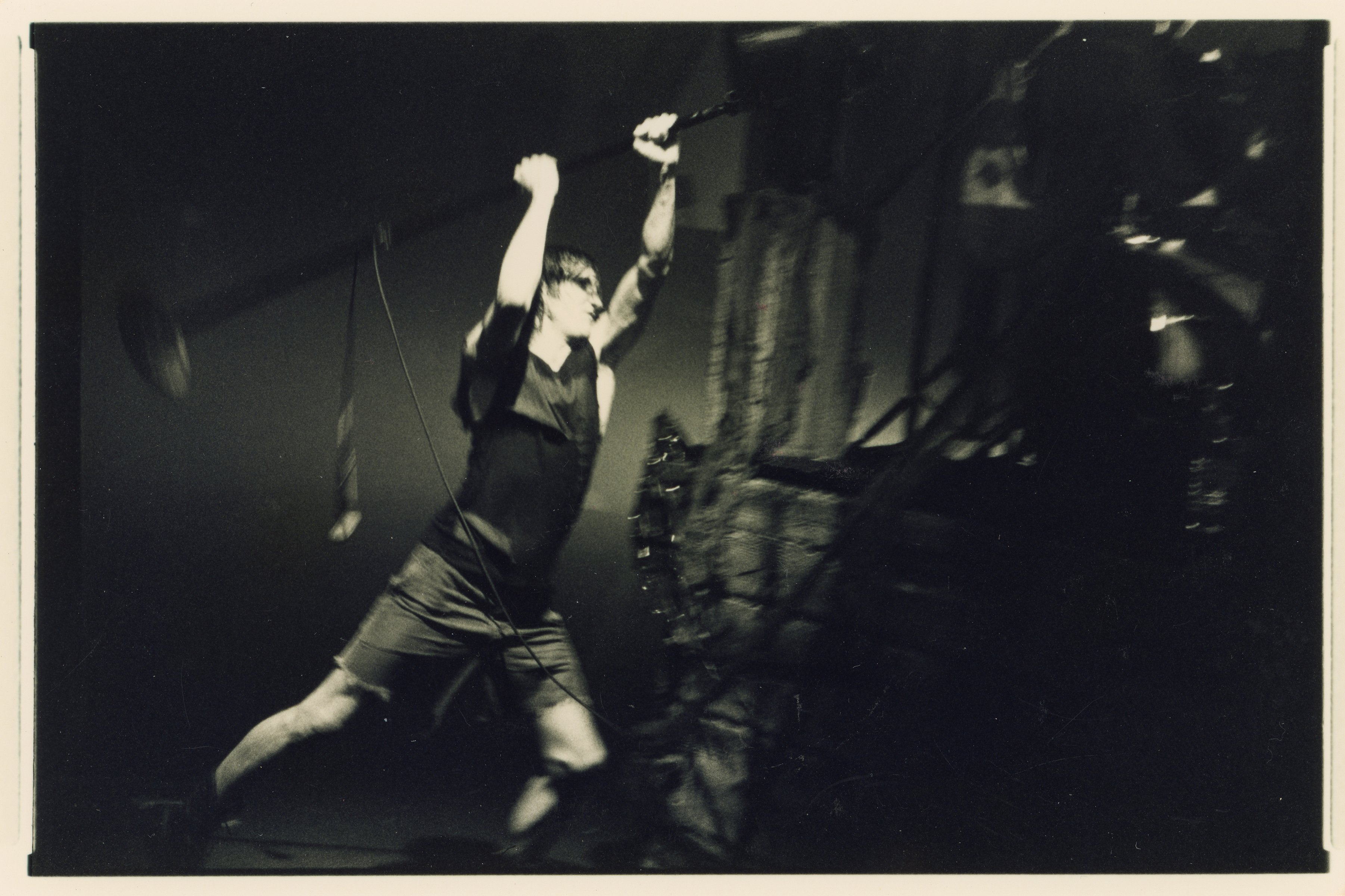

I think there was an element of controlled chaos. It was just very real and emotional, and I think the musicians, after a while, got in the same course of the emotions of it all. So everybody knew when things would spin out of control, and when a mic stand would be thrown. You started learning the rhythm of it all.

“Every show felt different and new and had a new emotional energy to it. It was very layered, and there was a lot going on.”

As long as he’s not throwing it at you!

Well, yeah. You learn where not to be, and sometimes if you get that wrong, then you’re kind of in a dangerous way. But the shows were phenomenal. The energy was insane.

The Downward Spiral is a very intense album. How did you listen to that every night? Did it get draining for you?

It was very intense. I think in being a quality, layered piece of work, after many listens to it you discover things all the time. So it never felt old or stagnant or repetitious, but every show felt different and new and had a new emotional energy to it. It was very layered, and there was a lot going on.

After being on the road with him and the band for almost two years, what did you learn about Trent and his music that perhaps you wouldn’t have without that level of exposure?

He’s more normal than you’d think. He’s a very grounded, levelheaded person. When you can see it from the outside it seems like this person’s out of control, but it’s a little more thought-out than you would think.

You later photographed artists like David Bowie, Lou Reed, Janet Jackson, and Audioslave, and you directed 2009’s The Warped Tour Documentary. How did this initial experience influence your other photography work afterward?

What an incredible place to start. It just raised the bar and everything to come after. It trained me to look for the emotional storyline of any artist you’re out with. Not trying just to get the perfect picture, but trying to capture the emotion. Sometimes something’s out of focus. It doesn’t seem like it’s framed right. It’s a moment you wouldn’t think is something of importance. You start getting away from the technical—overthinking it—and it’s more of just the emotion of feeling it.

Sometimes the perfect photo isn’t the one you expect.

People resonate with ones that I would never think they’d resonate with. There’s one of Trent who’s resting in a theater, sitting in a chair. It was the last one I included in the series, and people are always purchasing the print for that one.

You have a shot of Bowie from his tour with NIN. What was he like?

He was such a great guy, such a gentleman. He was inspiring to all of us. He was witnessing this younger band going through it. Nine Inch Nails were very young back then, and he’s like, “Been there, done that.” He’d figured out his pace and how to maneuver through all the craziness. I think David was trying to write from a certain place in the early ’90s, and I think Trent was that artist that was writing in the same kind of way. I think they just found each other.

Do you have a favorite photo from this exhibit?

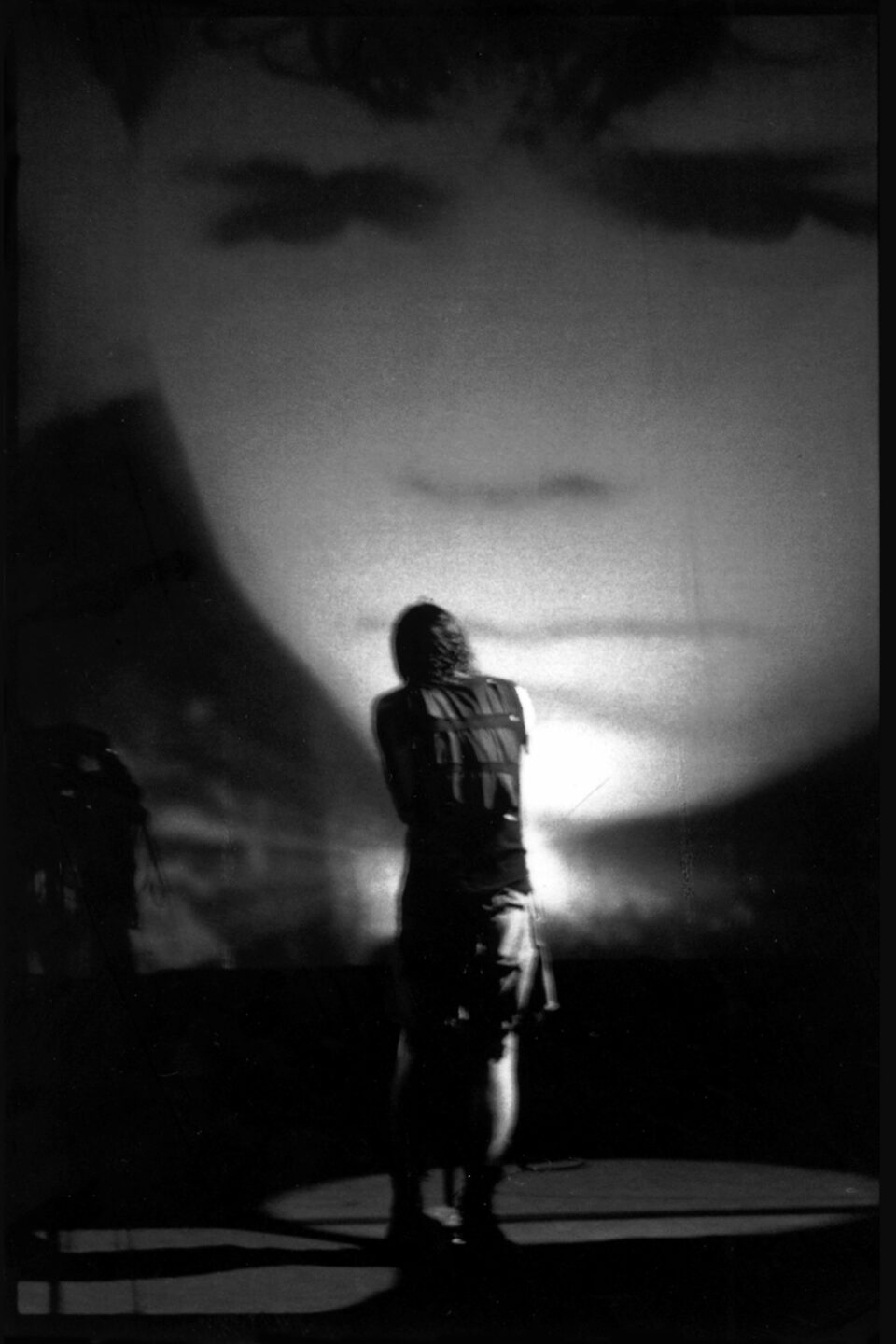

It’s called “Hurt.” I’m on the stage, Trent’s behind the screen. It’s just [showing] a boy, but there were a lot of dark images. And the fact that I caught that boy in his eyes, it just symbolized one side of the dynamics of the tour for me, where this [aggressive live shot] might be the other end of it. You have more somber over there, and you have more of the angst over here.

Was there any one show that really stuck out to you as the most memorable?

Yes, the last performance of the tour. Trent wanted to take it back to the club level, and that show in Miami was the most hardcore, raw-punk performance of the entire two years of touring. Everyone gave it their all, and I also felt like the coverage just all fell into place. I felt as though that performance with no edits in the footage could be watched from start to finish of the entire set and would be the greatest “bootleg” coverage of the “Self Destruct” tour.

Looking back at the Closure film, what are your favorite moments? Did your photo work help inform how you shot video?

For me, as trivial as it was, I loved that I caught the exit sign being taken down. Everyone was throwing everything at the exit sign in the dressing room to bring it down, and eventually it was Trent that brought it down and a celebration ensued. What most don’t know is as they were throwing things at it, on the other side of that wall the tour manager, Mark O’Shea, was doing settlement with the promoter. They decided to wait on the final number until they stopped hearing destruction in the other room. To me, it was a classic moment of dressing room destruction on the road. FL