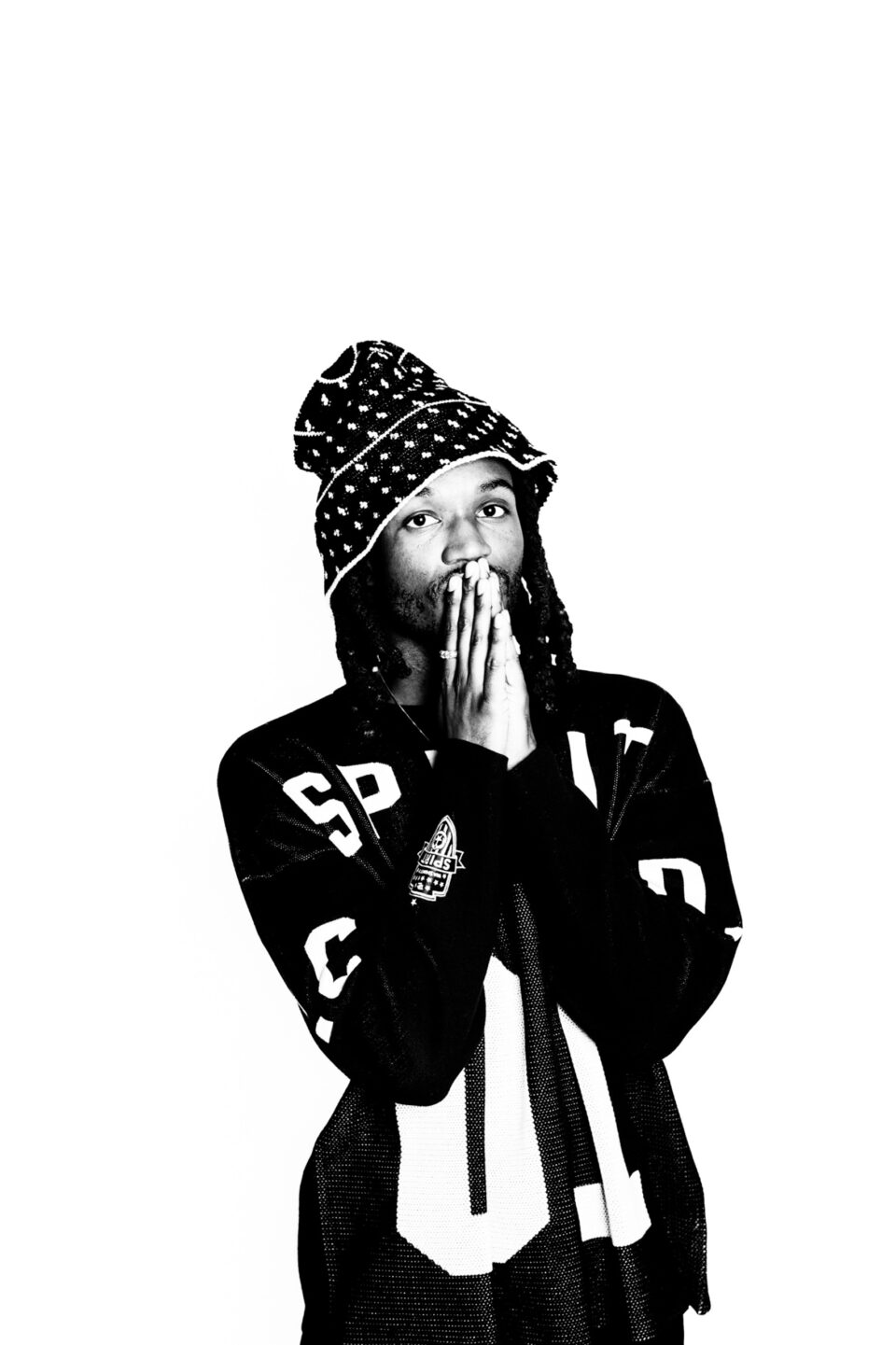

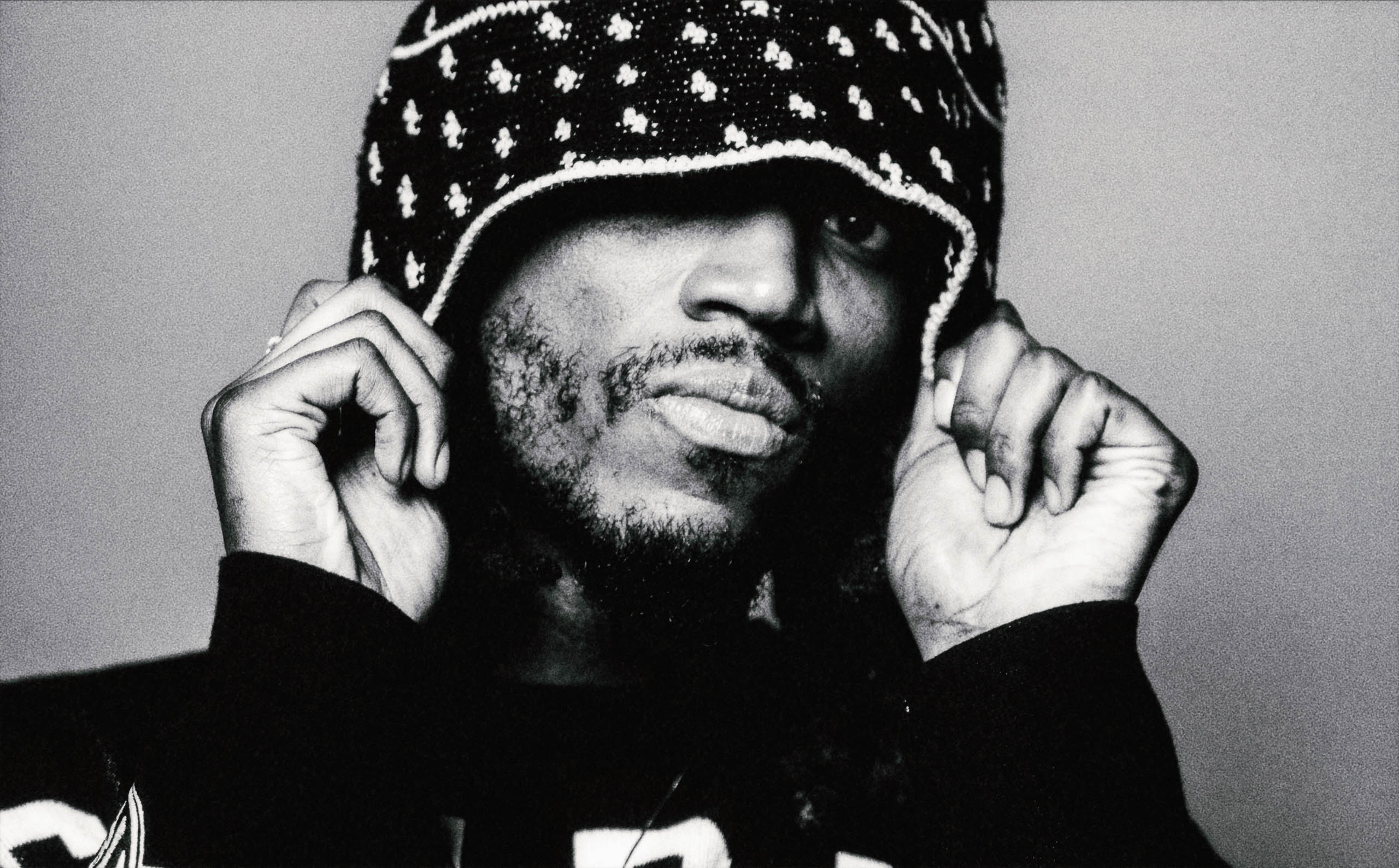

Saba’s been waiting on this one for a looong time. The Pivot Gang co-founder began plotting From the Private Collection of Saba and No I.D., his album with production legend and fellow Chicagoan No I.D., in 2022. This was back when Saba was gearing up to tour in support of his solo LP from that same year, Few Good Things. The plan was to drop a tape as a thank you to fans during the run up to the tour, but as Saba kept writing on beats from the Windy City icon whose credits include production for Common and JAY-Z, the results kept getting better with practice. He hit pause, hit the road, and rededicated himself to the project after getting back from tour.

By his estimate, Saba recorded 40 to 50 songs with No I.D., though it wasn’t until the duo began working on “Westside Bound Pt. 4,” the emotional center of the new album, that the full scope of the vision began to sharpen into focus. The track plays as both a family history—the exploration of generational roots in Chicago music—and a look at the city that shaped him. It was from this place that Private Collection really began to cohere. It was an arduous and sometimes frustrating process, but Saba, in the measured and thoughtful manner he’s come to be known for, took the delays in stride. In the end, it’s more than just an album—it’s a shared history, a testament to city and family, to community and the people within it.

With the album out earlier this week, we spoke with the emcee about the process of making Private Collection, dating all the way back to his childhood as a studio rat.

When did the collaboration with No I.D. turn from just messing around to having an album on your hands?

We went into it with that as the goal, I think. There was one song that was missing from the album the whole time, something that was preventing it from being done. It ended up being “Westside Bound Pt. 4.” I think the context and the story that I’m telling there, and just wanting to feel like it’s vocalized on the album, is important—what it represents to me, why it’s important to me. I also wanted to touch on my family and the generations that came before me. Once that song had a demo, I felt like we had an album.

Was it difficult getting to a place of emotional vulnerability with that track?

I wouldn’t call it difficult, but it was something that required patience. As an artist, when you know that you’re searching for a feeling, sometimes it’s hard—especially when the music sounds good already. Sometimes it’s hard to describe that to somebody who’s not in your brain. It’s like, “I’m not looking for it to sound good, I’m looking for it to express something right down there [points to his heart].” I need something to sound how I feel. That’s the real search, and it can be kind of isolating. Everyone else’s job is finished and it’s just on you at that point. Making this record was like a tennis match where the ball would be in my court, then I would do something and it’s in No I.D.’s court. It was a conversation that worked like that for many months.

“I need something to sound how I feel. That’s the real search, and it can be kind of isolating. Everyone else’s job is finished and it’s just on you at that point.”

You’ve discussed how working with No I.D. allowed you to access stuff that you’d previously been unable to touch. What about his style made you tap into something new?

No I.D. is a really great producer, and not just in the sense that he makes good beats. He goes into the sessions with the goal of extracting information from the artist so that the music all ends up having a direction. As a Chicago artist, it’s always been a dream of mine to make music that sounds like this. He’s a catalyst for that in a lot of ways, where his sonic landscape gives me that nostalgic feeling. It feels soulful. It feels like a part of the story of being from Chicago. More literally, too, because I’m working at his studio, there’s access to some crazy synthesizer I’ve never seen in my life. In the music equipment department, he has seemingly unlimited resources.

I know there were a lot of starts and stops with the project, too. Did that get frustrating?

I can’t say they were frustrating, because a lot of times they were based on things that are much deeper than music. I can’t force the album knowing some of the things that are being balanced.

“It’s always been a dream of mine to make music like this. [No I.D. is] a catalyst for that in a lot of ways, where his sonic landscape gives me that nostalgic feeling. It feels like a part of the story of being from Chicago.”

By that same token, is it tough to take a step back when there’s momentum?

As the artist, it always feels different than the version the fans are experiencing. It’s not the momentum for me. The goal hasn’t changed. The goal’s been to get the music out, and I’m embracing whatever ride it takes to get there. I’m the person who knows what we’re actually up against, what some of the challenges actually are. I have a lot more grace for myself. I’m already doing something that I know a lot of people have tried to do, and it’s been very, very challenging to get it done. There are going to be bumps and bruises, there are going to be starts, stops, and all of the shit that comes with it.

Was your faith ever tested, or did you always know it would get finished one day?

The thing that was my silver lining was that the album kept getting better. I just had to trust the process. That was the thing that I kept having to remind myself. I couldn’t really get caught in the idea that it’s something that people are waiting for. My relationship to the music isn’t the same—it’s not something that I’m waiting for, it’s something that I’m delivering. It took a lot of mental fortitude where I had to build myself into a new version of myself over the last two, three years. It’s for the betterment of the music at the end of the day, but I think it also made me more sure of myself and more confident in my music.

Tell me about the title, Private Collection.

This project has gone through so many phases. It originally started as a mixtape around the tour for Few Good Things back in 2022. I’d talked to No I.D. around that time, and he sent me a bunch of beats. I felt like he was taking a shot on me. Not everybody has access to hundreds of beats from one of the real greats in hip-hop. Being from Chicago, it was that much more important to me. I wanted to live up to that. I didn’t care that I was going on tour. I wanted to show that I was going to do my part. So I went on that tour. I did 14 songs from the road, and that was the goal: “Let’s just go on tour and drop it, whatever it is, when I’m done.” After getting home, I realized that the music we were making kept getting better. So I’m like, “Why rush it?”

A lot of people who listen to my music really engage with it. They give it time, and that’s something that I have to respect. I have to adjust, I have to do my fair share as the artist, especially in this day and age where not everybody has access to a fanbase that’s willing to grow with that, that’s going to be willing to sit and dissect the songs and see how it connects. I didn’t know when I’d get the opportunity to work with No I.D. again, so I wanted to make sure I gave it all that I have.

Tell me about the lineage of artists and music makers in your family.

I really grew up in studios. My uncle, my father, and my grandfather all kept it so real. I’m nine years old making beats. My granddad was always on me. If I didn’t know how to do something and I’d ask him how to do it, he’d open a book and read it and show me how to do it. I recognize as I get older how unique of an upbringing that is. There’s a comfort there, too. When I go to the studio, I’m comfortable searching for the destination. I don’t think people realize how much that does for a family. I feel like in a lot of ways I’m the collective dream of a lot of people.

“I really grew up in studios... I recognize as I get older how unique of an upbringing that is... I feel like in a lot of ways I’m the collective dream of a lot of people.”

My mom’s cousin, who I sampled on “Westside Bound Pt. 4,” was also really doing shit. I had a great uncle who was in a group called The Sheppards in the ’60s. I never got to meet him. He passed away in the ’80s, but he was on his guitar and that led to my grandfather being on his guitar, which led to him having a studio. That led to my dad doing music and my dad being in the crowd that he’s in, ending up linking with No I.D. in the ’90s, to me coming along later. I grew up with my mom. I didn’t grow up with my father in that same way. We saw that family a few times a year, but seeing how the story just unfolds is so cool. I couldn’t write this.

My uncle, one of the coldest producers that I’d ever known—all we wanted when we was young was for him to like our music, because he didn’t give a fuck if we was young. He had a standard and it was like bootcamp. We wanted to get a beat from him. It’s so surreal how this shit played out in life, where one of his last beats he sends to me I got No I.D. to do the drums, and then I write a song to it and then my uncle passes away. Some of his closest friends have told me, “Man, that’s like his personal GRAMMY: he got to do a song with his nephew and No I.D.” Some of that shit be so heavy. My grandfather who got me into music, he didn’t have the relationship to music that I had. It didn’t work like that for him, so he didn’t want me to pursue it, because he couldn’t see success.

Has that informed your thoughts about life and death?

Yeah, I be floating through this motherfucker because I can sit right here and come up with my own plan and my own version of it. But a lot of times, time is the greatest storyteller. This shit is feeling cosmic in a way that’s beyond my paygrade. Serendipity took me a long way. I know I got to work hard and put myself in a position to be there when it happens, but you never know when it’s going to happen or what it’s going to look like, because based on how any of this shit has gone so far, I couldn’t predict none of it. FL