During a press trip to Italy while promoting his 2005 cult horror thriller Hostel, Eli Roth fell in love with the country. He was a fan of its movies, its culture, the sexy vision of the ’70s the nation exported to American televisions and radio stations. During that press trip, he bought a bunch of DVDs—silly, raunchy comedies equal parts uproarious and subversive. The soundtracks were stellar, all seemingly distributed by a company called CAM Sugar, which he had no way of tracking down.

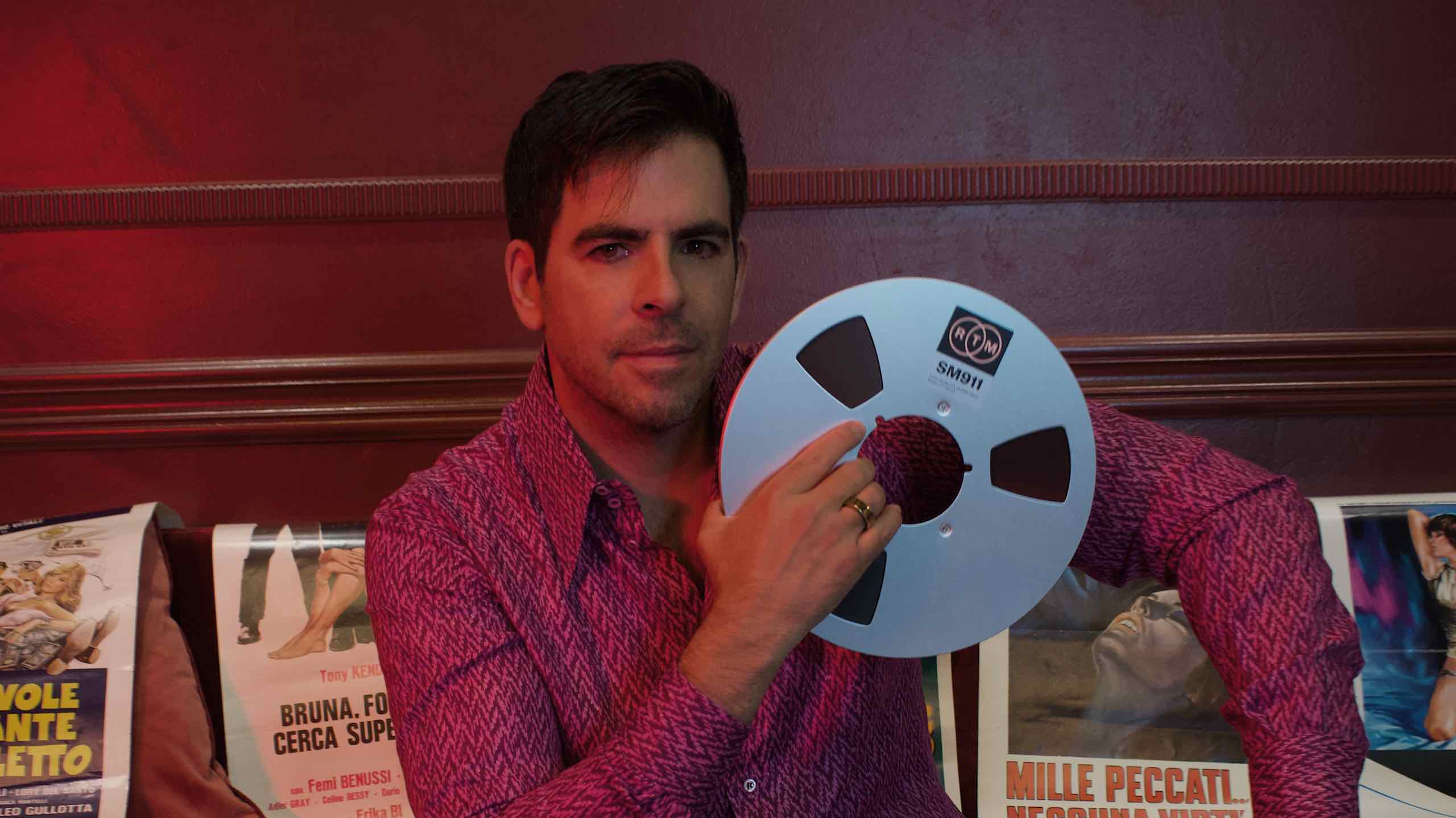

Thanks to a fateful Instagram encounter with a friend who happened to be visiting CAM Sugar headquarters, before long Roth not only had an in to tour the company’s massive library, but was also recruited to put together a compilation of his favorite soundtrack jams from ’70s Italian cinema. As such, we’ve arrived at Eli Roth’s Red Light Disco: Dancefloor Seductions From Italian Sexploitation Cinema, a passionately crafted ode to Roth’s favorite cuts, complete with liner notes he penned himself. Many of the songs have never been released outside of the films in which they were featured.

To get some more information on how this delightful comp came together, we caught up with Roth to chat about whittling down the track list from 500 songs, the renaissance of overlooked Italian directors, and why Quentin Tarantino is the GOAT when it comes to movie soundtracks.

When did your fascination with this very specific era of music history begin?

With Hostel, I got to go to Italy. I’d been there once before, but I never really spent a lot of time in Rome or traveled around. I met journalists, and someone took me to a DVD store. There were these crazy sex comedies that I'd never heard of. They had very, very specific artwork—like, someone in a Halloween costume of a sexy police officer, a military nurse, and a buffoonish Italian guy falling—all over them. I was like, “What are these movies?” This label called Federal Video put them out and I bought all of them.

It looked like they were dumped from VHS onto DVD. They’re not pristine transfers, but the movies are so funny. I became obsessed with these films. There was this whole treasure chest of movies that had never made it over to the US. I started watching the films and listening to the music, and I love the songs and I love the style. The cars, the ashtrays, the couches, the lamps, the rugs, the wallpaper—I just want to live in that world of ’70s and early ’80s Italy.

How do you go from this place of admiration to actually putting out music associated with this era of Italian cinema?

I loved the music, but I could never find it. I saw this movie when I was a kid called Pieces, and it said the music was by something called CAM. Someone explained to me that CAM is a music library, so I always knew it as an Oz-like place where you walk in and there were just thousands and thousands of original scores. My friend Alix Brown is a DJ and music supervisor, and I saw on her Instagram that she was in Milan, and she took a photo at the CAM Sugar headquarters. I said, “Oh my god, I can't believe you’re there, I would die to get into that archive.”

“The cars, the ashtrays, the couches, the lamps, the rugs, the wallpaper—I just want to live in that world of ’70s and early ’80s Italy.”

She told them, and they said that they wanted to start releasing this music. They asked if I wanted to do a compilation. They’d just done one around horror music at that time, so they wanted to do something different, and they said maybe some of that sexy Italian disco music. I’m like, “Absolutely,” because that music is amazing. There’s an archivist named Andrea Fabrizii and he’s in charge of the 8,000 titles they have. He helped me narrow it down to 400 or 500, so it was manageable to pick from that.

How did you narrow it down?

Andrea gave me full scores so I could identify my favorite moments. I just started to narrow it down to the top 100, and then I just auditioned all the songs. That’s why we spent a year doing it. There was no rush for it, no date that we had to hit. I was traveling a lot last year, going to different horror conventions, and I’d have full travel days. I was just listening the whole time. If I was making a movie, I wouldn’t have been able to do it this way.

Was your relationship with Italy as a country pretty significant before you discovered this weird movie culture?

When I went to Italy with Hostel, I felt like I was right at home. After Hostel II, I did a whole trip in Capri and I met Dario and Asia Argento. I thought, “These people understand me, and I love their movies.” Everyone knew the “inis”—Pasolini and Fellini—but there was so much more. The Italian critics didn’t know anything about it, but the fans did. Quentin [Tarantino] was like, “You guys shit on your greatest director, none of you will even acknowledge him,” referring to Sergio Leone. Quentin said that in 2004. Things are finally starting to come around and other directors are being appreciated now.

Are you a vinyl person, as well?

Absolutely. I mean, I grew up on vinyl and then got away from it with CDs and then thought, “Oh wow, my iPod is everything,” and now I’m back to vinyl. We all are. Everyone’s going back to cassette tapes, too. Once I really started collecting, I realized how much stuff wasn’t digitized and wasn’t out there, and how rare it is and how valuable it is. My wife will go to Italy and pull certain pop artists, and Quentin has a record room. I always thought that was really cool. I love the ceremony of playing an album and listening in the order it was supposed to be listened to and getting up and flipping the sides.

“Everyone knew the ‘inis’—Pasolini and Fellini—but there was so much more. The Italian critics didn’t know anything about it, but the fans did.”

How did you go about assembling the liner notes for the project?

The liner notes were fun. I wanted to make it inviting. I don’t like when people are like, “I’m an expert, you’ve never heard of this.” It’s daunting. I always try to be a sommelier where I can recommend beginning, middle, advanced. Even if you’re an audiophile or a hardcore soundtrack person, there’s stuff on here you won’t recognize.

Do you think this experience will change how you make movies in the future?

I’ve had CDs of a lot of this stuff, so there are a lot of cues I’ve tried to use, but I could never get to the owner. Music supervisors would be like, “Yeah, this stuff is really hard to track down.” Now that I have access to this archive, when I’m writing, I can get a song before I make the film so I can shoot the sequence to the song.

Is that a game changer for you?

It doesn’t change everything, but it adds something to the arsenal. Now, before I go and make a film or when I’m editing a film, I can talk to my friends at CAM and say, “What would fit with this?” I get to work with amazing composers, and I love it, but it’s cool when you can put in a song that’s a callback to a very specific, obscure thing. It’s a reference for 10 people, but the ones that get it get it. I like doing a mix of a very beautiful score, throwing in some banger songs everyone knows, and then just some obscure ones that I love. Quentin’s the guru. Quentin, I think, changed music soundtracks. He was the biggest influence on me that way. FL