Sufjan Stevens

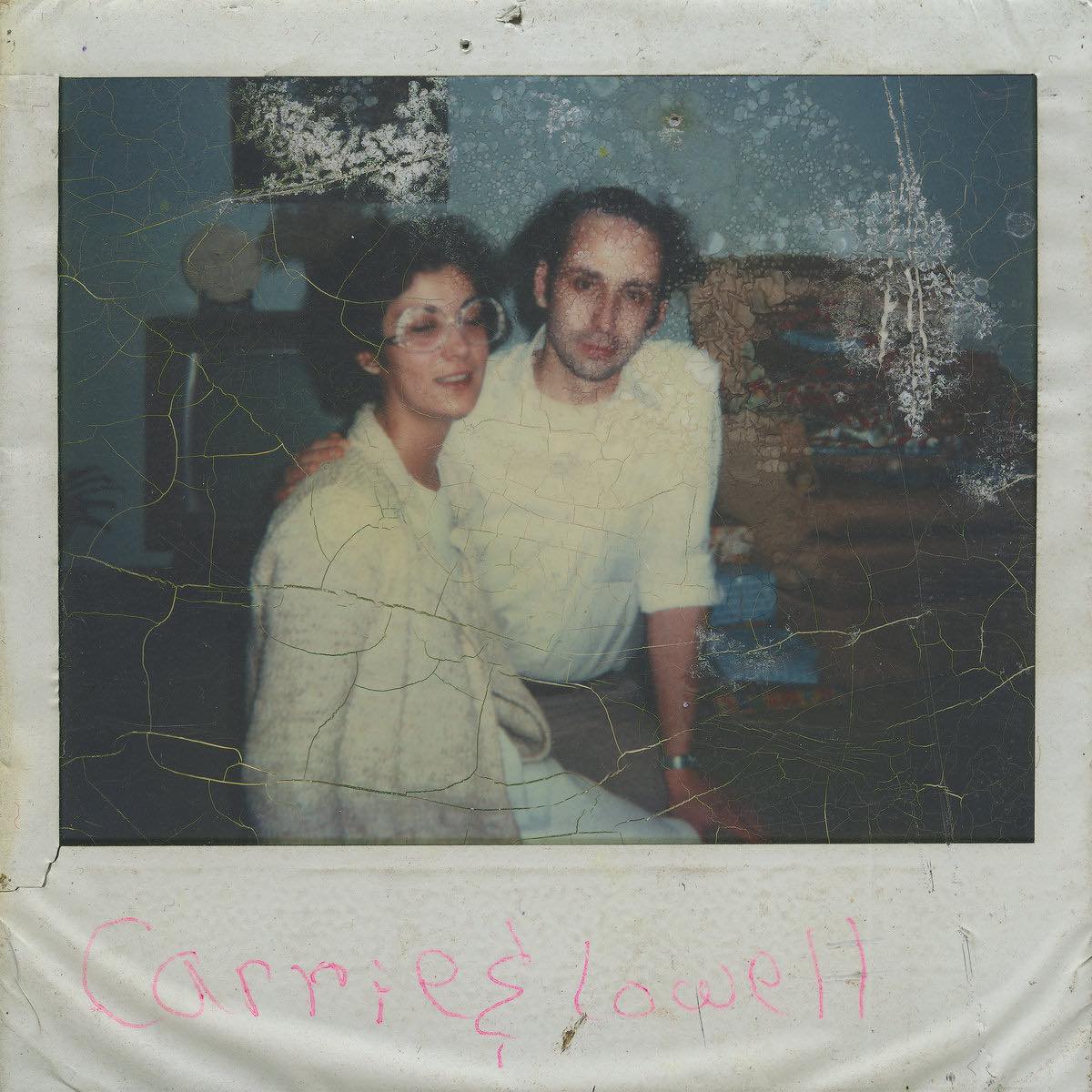

Carrie & Lowell [10th Anniversary Edition]

ASTHMATIC KITTY

Sincerity can be such a turnoff—especially our own. Think of an old diary entry, an expulsion of feeling, raw and unmediated. It’s never easy to return to such a thought, no matter how real it felt in the moment, or how far it feels from our present. Perhaps it should come as no surprise, then, to learn as we did last week via an incredible interview on NPR’s All Songs Considered that Sufjan Stevens has little love for his totemic 2015 record Carrie & Lowell, an album that celebrates its 10th birthday with a new reissue. After all, it’s an album of unabashed sincerity, a gut-wrenching document of a dark period in Stevens’ life following his mother’s death, one he still doesn’t seem to fully understand. “I was being manipulative and self-centered and solipsistic and self-loathing,” Stevens told host Robin Hilton. “I’m kind of embarrassed by this album, to be honest with you.”

And yet here he is, returning to Carrie & Lowell once again following Carrie & Lowell Live and the outtakes/B-sides collection The Greatest Gift, both from 2017. What compels him, then, to continue this parade of self-loathing, this tour of contrition for a work that never achieved the goals he’d hoped it would? Even the most cynical of conclusions—the one that answers most reissue queries—only confirms a demand he seems at odds with, one that highlights our collective desire to revel in his misery in yet another way. Whether he wants anything to do with it, his fans can’t seem to quit it, and so we once again head out for another long drive into the 1980s Eugene, Oregon of his memory.

When Carrie & Lowell first appeared back in 2015, it was largely viewed as a return to the sparse folk of his earlier albums and away from the ornate synth-pop of his then-recent work. In Rolling Stone, critic Jill Mapes identified the “acoustic fingerpicking and warm-milk voice” as the ideal form for the deep anguish driving the record. To his credit, Stevens didn’t shy away from the personal turmoil inherent in what amounted to an album-length eulogy that tracked the grief of losing a mother who remained largely an enigma even in her final moments. Where his past records preferred the arms-length detachment of mysticism and metaphor, Carrie & Lowell was almost painfully naked in its pursuit of something close to revelation. “I’m prone to making my life, my family, and the world around me complicit in my cosmic fable,” he told Pitchfork back in 2015. “With this record, I needed to extract myself out of this environment of make-believe.”

The result is a collection of songs that sound like the grainy footage of attic-bound home movies, snippets with and without context that explain nothing, but mean quite a lot. Video-store abandonment, a cool Oregon breeze, light through a lemon tree, and imagined pet names serve as specificity propping up a mystery Stevens is determined to explore even in the absence of any sort of resolution. “What’s the point of singing songs / If they’ll never really hear you,” he sings on “Eugene,” introducing the self-recrimination that’s seemed to seep its way into Stevens’ view of the record as a whole. “In my mind, the songs on Carrie & Lowell are the messy evidence of owning up to my own misery, depression, dread and grief,” writes Stevens in a new essay accompanying the album’s reissue. “I was a fake, a failure, and a fool to ever believe my art could save me.”

In addition to the essay, the 10th anniversary edition includes a number of previously unreleased demos from the record, as well as a scrapbook featuring photos of Stevens and his family in the years surrounding the events recounted on Carrie & Lowell. Most of this ephemera isn’t particularly revelatory, and will appeal to only the most fervent completists, though there is a moment that gets at the antipathy he seems to hold for what may be his most celebrated record. The final demo on the release is noted as the fourth version of “Fourth of July,” a song he’s said took many forms over its evolution. This particular cut, though, comes in at almost three times the length of the original. While it begins much the same as the album version—soft piano and softer vocals framing the moments Stevens first heard news of his mother’s passing—it ends with an extended ambient piece, a wave of atmospheric synth washing over the song’s matter-of-fact refrain “we’re all gonna die.”

In that recent NPR interview, Stevens talked about his move away from lyrical work as of late, and you get the sense that this version of “Fourth of July”—which favors formless emotion over explanation, feeling over fact—seems to him a better eulogy for a mother he could never quite know in the way he wished, and whose death remains as slippery a concept as ever.