“My son’s asleep,” Natalie Bergman whispers when I arrive at her hilltop home in one of Los Angeles’ quiet residential neighborhoods on a Sunday afternoon to talk about her new album, My Home Is Not in This World. We continue speaking in hushed tones as she leads me through the living room, which boasts a breathtaking view of the city. At the dining table, she offers golden croissants, fresh berries, and coffee, even suggesting a sandwich. I settle on water, and she pads to the kitchen to fetch it. She’s barefoot, wearing a vertically striped oversized button-down and butterfly-appliquéd jeans that add a bit of pizzazz to her casual look.

Her home reflects her understated chic—organic and simple décor in blacks, warm woods, and muted tones. A grand piano sits in one corner with The Joni Mitchell Songbook and Making Things: The Handbook of Creative Discovery arranged side-by-side on the music desk.

Back with my water, Natalie tucks herself into the couch. She’s makeup-free, her hair loose, and somehow even more striking than in her beautifully curated Instagram grid. Just being around her is calming. So when she gently asks if everything went OK after I rescheduled our interview to attend a memorial for my friend’s daughter, I break down crying. As I tug at the necklace that reminds me of the young girl, I share my history with the family. Natalie’s quiet presence, her generous spirit, and deep sensitivity create a space that feels like crawling into the softest bed, under the coziest comforter, and letting go.

Bergman is no stranger to loss. Her mother, an award-winning writer, died of brain cancer when Natalie was just 16. Her father and stepmother were killed by a drunk driver in 2019. Even her mother’s sister, Anne Heche, died from injuries sustained in a car accident. Now 35, Natalie carries a hard-earned perspective on grief—one I wish she didn’t need to have, but in this moment I’m grateful to experience it.

Music has marked every major moment in Natalie’s life. She began playing early, but after her mother’s death, she also started writing lyrics. “That was my way to express myself,” she says. Her brother, Elliot Bergman, eight years her senior, pulled her out of school and took her on tour with his band, Nomo. “Playing with my brother and being able to—not escape from my grief, but put my grief into something creative—that was a special time in my life. I found music in a new way, and in a way, it saved me.” From Nomo, the siblings transitioned to their reggae-influenced indie-pop group Wild Belle, releasing three albums. While touring their third, Everybody One of a Kind, they received the news of their father’s death. Natalie stepped back, and from that break came her 2021 solo debut, Mercy.

“Writing the music was such a beautiful way for me to go through my grief,” she says. “But I didn’t actually have a moment to just shut off and tune out. I started writing almost immediately after [my father] died. And then the record came out and I was promoting; I was doing shows and interviews and touring. After that, I was like, ‘Wait a minute, I need to cry in my bed for a few years.’ And so I did that for a little while, and I wasn’t really able to write.”

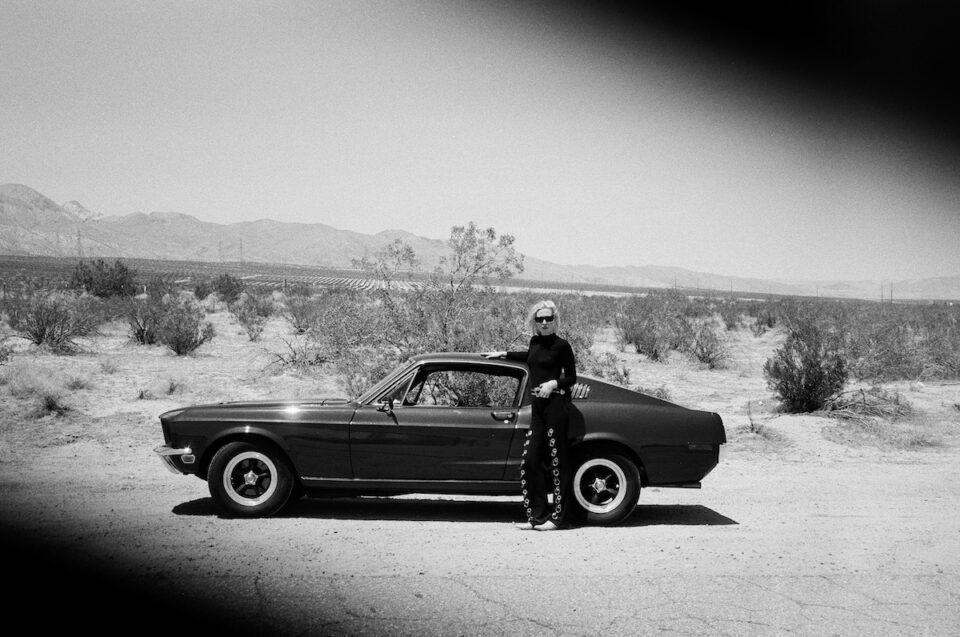

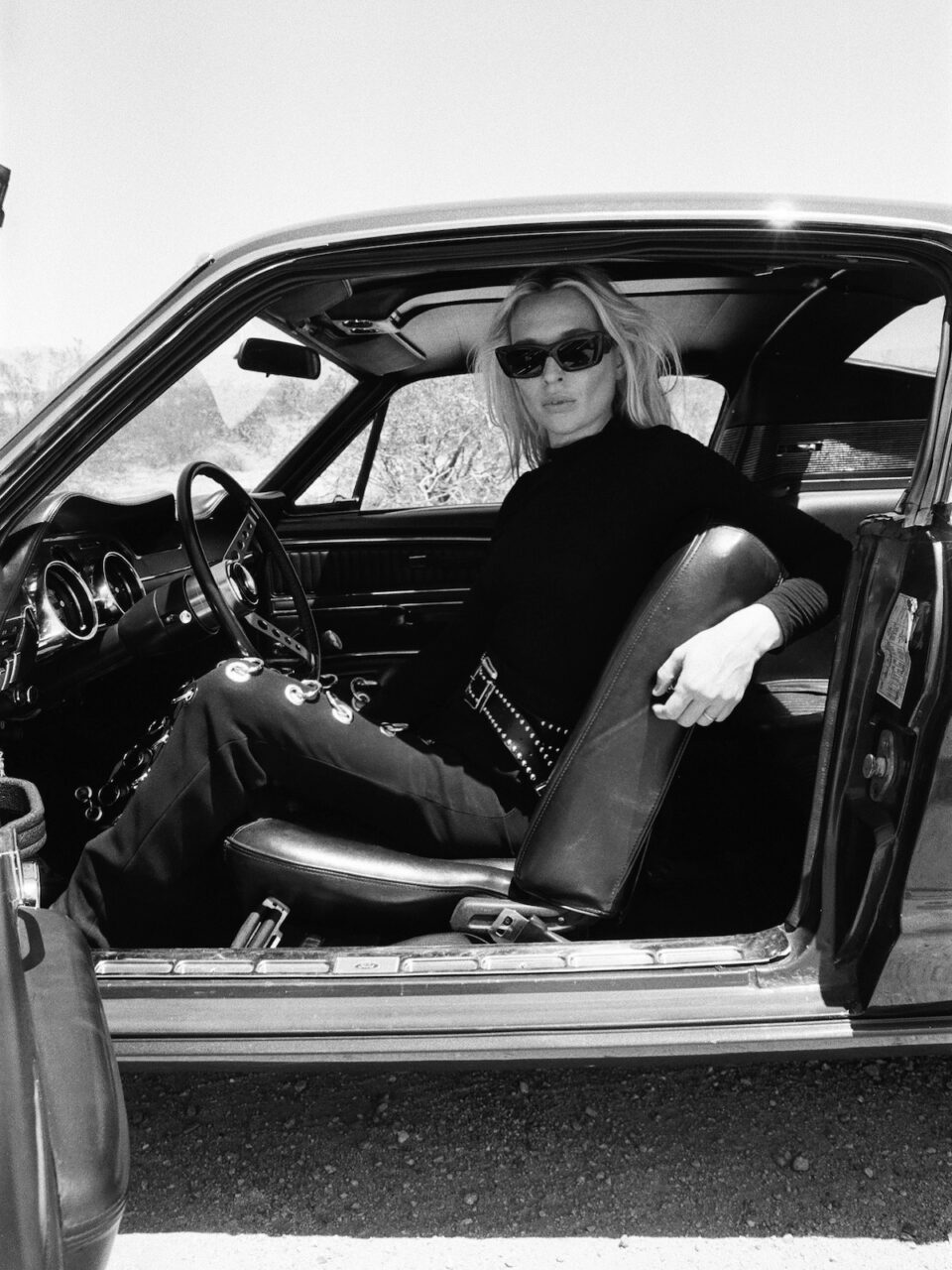

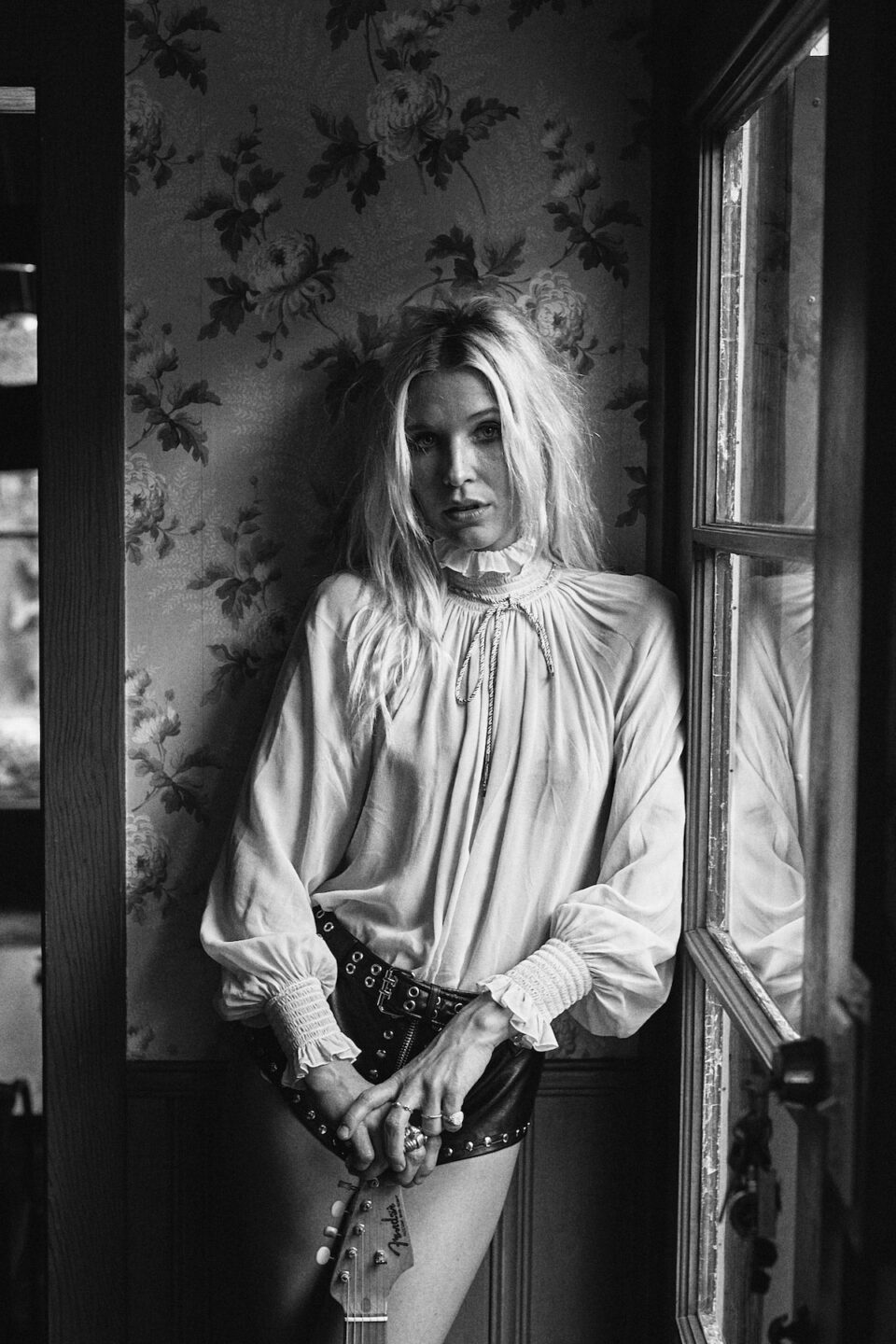

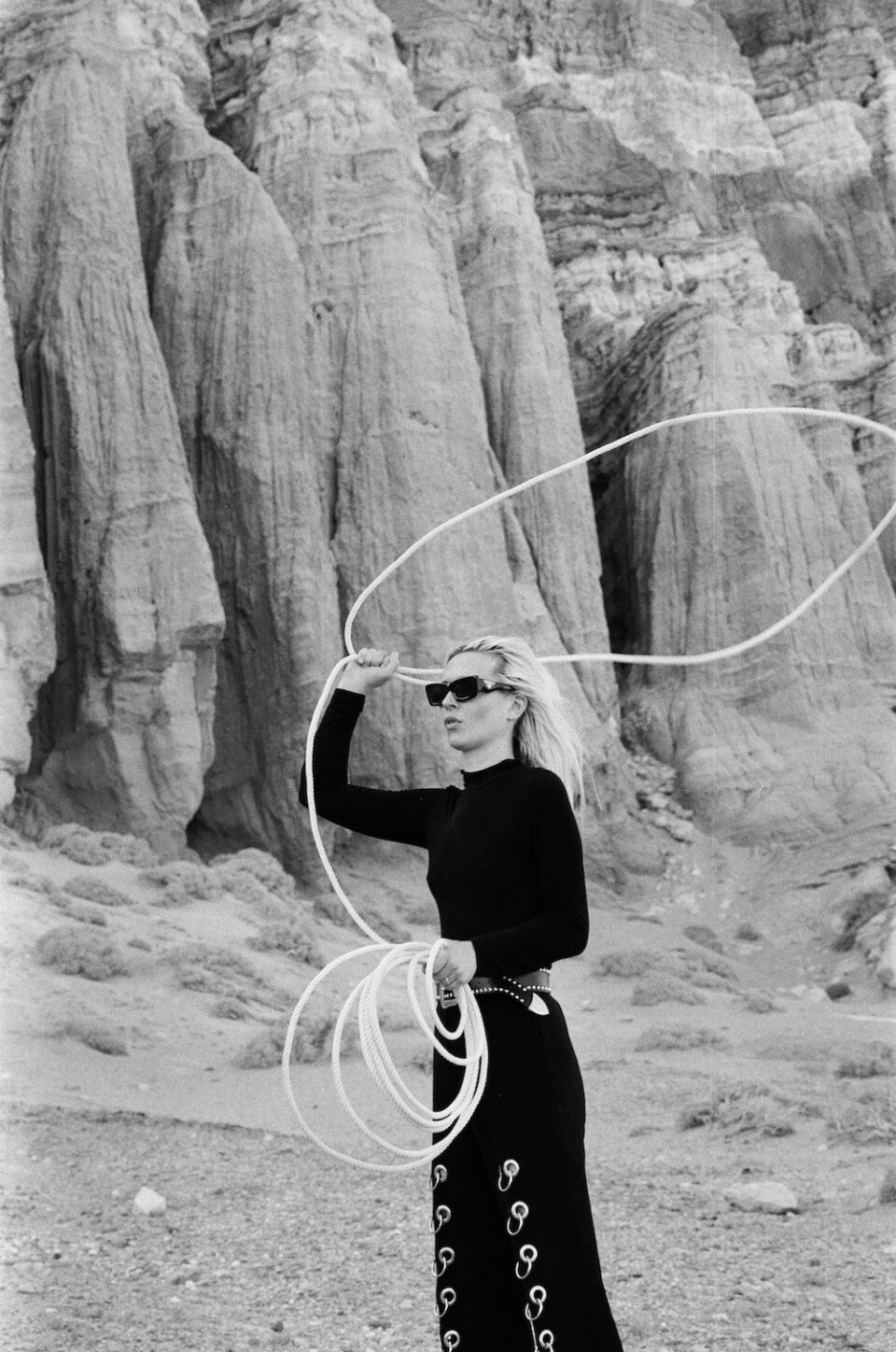

photo by Leslie Kirchhoff

“I wanted to make something hopeful while also questioning our place as artists on this planet. When we don’t feel like we belong, it’s part of our job to make music that invites people in.”

The delayed reaction surprised her, but it deepened her understanding of grief. “I went through my darkest, deepest sadness after getting off that tour,” she says. “I thought I went through it. I took some time alone. I went to the desert. I was quiet. I made this body of work. But grief is an ongoing process. Death doesn’t leave you. It changes and takes a new shape as you go on.”

We’re taking turns crying now, as Natalie pushes back tears. She shares that after her mother’s death, she went “full-blown dark…doing whatever I could get my hands on: alcohol, drugs. I knew that was a horrible way of dealing with death.” Her father’s death had the opposite effect. “I did everything to honor him, including not being the party animal that I was. Alcohol took my father’s life, so I got sober.” Sobriety, she believes, cleared the path for her to meet her husband, Andreas, which led to the birth of their 18-month-old son, Arthur—“who showed me new life.” That spark of new life inspired My Home Is Not in This World. She admits she was initially hesitant to write about a love story, the central theme of the new album. “I felt a little ashamed,” she says. “But I think that’s what I need right now—a little respite in the joyfulness of life.”

Where Mercy leaned into overt Christian themes, My Home embeds its spirituality more subtly in songs of love and life, some of which take on hymn-like tones. That subtlety makes the album more accessible. “These are sweet stories about love and finding new love,” she says. “But the title also alludes to that home over yonder. I’ve always referenced that in my music because I’ve always felt a sense of not belonging. I wanted to make something hopeful while also questioning our place as artists on this planet. When we don’t feel like we belong, it’s part of our job to make music that invites people in.”

She recruited her “favorite collaborator” and sometimes-mentor Elliot to produce the album. They recorded partially in the woods, where he lives, making sculptures. “He listens to me—it’s a beautiful collaboration,” she says. “He’s like the ultimate party host. He knows people’s strengths and how to bring them together. And he’s an incredible musician. He’s the only person I’ve worked with who I don’t have to speak to with words.”

The healing journey between Mercy and My Home Is Not in This World is apparent when the albums are played in succession. Natalie has never worried about how people would receive her music. “That would torture me,” she says. She cared even less with Mercy, calling it a “solo, introspective sojourn.” She adds, “I didn’t give a fuck what people thought about me singing about Jesus. Some people were like, ‘This might be scary coming from Wild Belle, with this album literally saying Jesus’ name all over it.’ That didn’t cross my mind. I wasn’t afraid. At this point in my life, I’ve lost everything I love. Why would I care what anyone thinks about me? That’s why it resonated. It was an act of desperation. I needed to heal. I needed help, and I asked God for help. How could anyone have a problem with someone processing grief in a harmless way?”

“At this point in my life, I’ve lost everything I love. Why would I care what anyone thinks about me?”

My Home Is Not in This World leans into retro sounds—Motown rhythms, lush ’70s instrumentation, and Bee Gees–style harmonies, especially on “Please Don’t Go.” A few songs even carry a whisper of Christmas carols. Recorded with Daptone Records’ rhythm section on an Ampex tape machine—and dubbed again onto tape—the album has the warm crackles and pops that make analog so irresistible. Natalie’s voice, doubled on every track, fits naturally here: sometimes bold, sometimes gentle. The album’s sense of familiarity is what gives it its quiet brilliance—it feels like music you’ve known forever.

About her sonic and stylistic choices, Natalie simply says, “That’s the music I like listening to so that’s what I want to hear.” FL

photo by Leslie Kirchhoff