Saul Williams does it all. Catch him one day and he’s performing at a heavenly outdoor music venue alongside one of LA’s most exciting producers; the next, finishing up a graphic novel; and the one after that, earning acclaim for his supporting role in the biggest movie of 2025. While all this occurs, he remains one of the most outspoken American voices in the face of the genocide in Gaza, using his platform of almost 325,000 Instagram followers to amplify stories and perspectives from on the ground. Williams is the classical definition of an artist, a definition that’s been wiped clean by the algorithm, stuffed into a box and left in the attic by Spotify. And yet, Williams demands to be heard.

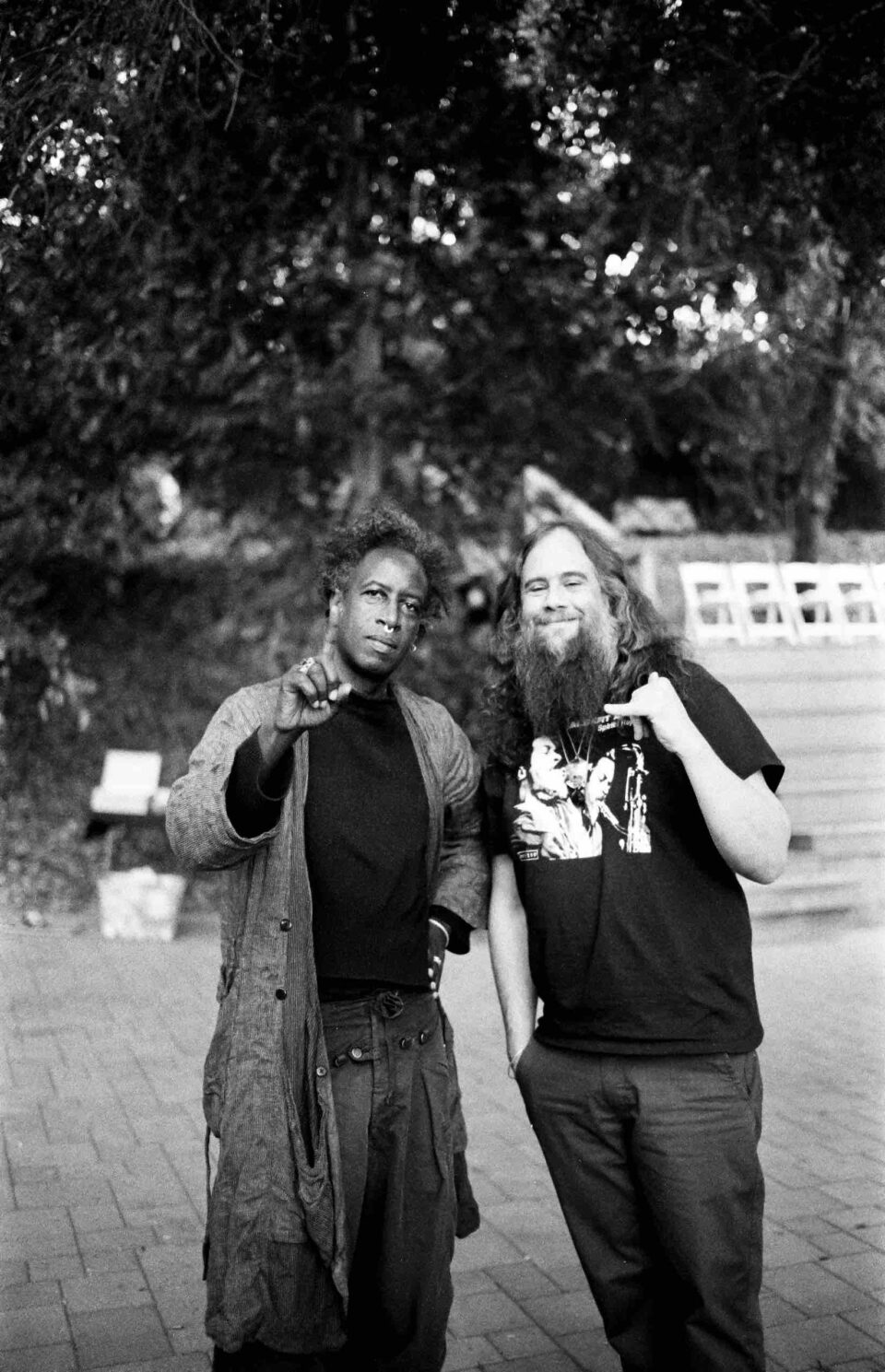

On the urgent and immensely powerful Saul Williams Meets Carlos Niño & Friends at TreePeople, Williams teamed up with the LA sound artist, producer, and André 3000 collaborator for a stunning performance. The show originally served as a preview for the music they would be releasing from studio sessions, but the performance went so well that they were encouraged to release it as its own entity. While new studio music is still on the way from the duo, this live release is a stirring entity in its own right, a testament to the power of collaboration, and, as Williams explains, deep listening.

With a physical edition of the record out now following the project’s digital release last month, we spoke with Williams about connecting with Niño over 25 years ago, the duo’s collaborative balance, and his passing encounters with André 3000.

This show was recorded at TreePeople. What does that venue mean to you two?

We live in Los Angeles and have for quite some time, so TreePeople has been a place that we’ve frequented for hikes. The LA style: you drive to walk. It’s all absurd. During COVID in particular, that became a place that we began to frequent, and ironically, we’d walk to that amphitheater where the concert took place and just sit there imagining what it might be like to put something on there. When Carlos and I decided that we were going to record an album together, we put together this concert to announce the fact that we were going into the studio. He suggested TreePeople and I jumped at the possibility. The people at International Anthem were huge supporters of it, so that’s how this show got released as an album. It’s completely freeform, completely improvised, and it’s a testament to the times.

This record demands your attention. What’s your preferred way to consume music at this point in your life?

I have a series of playlists that I put together based around different moods and what have you, and oftentimes I’ll also just put my entire digital library on shuffle. Certain songs begin to stand out, or I have that experience, like you mentioned: “I really just want to listen to what’s being said.” If I’m really trying to zone in, I also have playlists that are oriented toward certain projects, because there’s certain sounds and worlds that those ideas belong to. I’m talking about the process of writing poetry, the process of writing essays, and the process of writing screenplays.

This also feeds into the process of making music, because oftentimes it’s through hearing something that I’m like, “Wait a second.” I’ll hear a bass line or drums or a melody that drives me to turn off the music and turn on the recording devices and get into that zone. My impetus toward music is usually composition first. I have to be inspired to write to it, and it has to get to the point of it really making me feel like words would be a good addition to this thing for me to get to the point of writing to it.

“The first way that I traveled the world was through being cast in plays. A lot of times the experiences of the characters that I’d be asked to portray preceded my own individual experience.”

That’s the gift and the curse of being an artist. Everything you consume is inspiration.

Not only what you consume, but the whole emotional landscape of life—all the ups and downs. That’s something I learned early as an actor. The first way that I traveled the world was through literature, through reading, and through being cast in plays and imagining worlds. A lot of times the experiences of the characters that I’d be asked to portray preceded my own individual experience. You take account of your own process even in the most horrendous circumstances. When I lost my father, for example, I remember one moment of being like, “Ah, so this is what that feels like.” As an actor, just making a marker of loss—this is what I can channel now when I need to feel loss.

In Sinners you play a character closer to who your father was than to who you are. What was it like to live in that space?

I enjoyed it a lot. I love when I’m able to sink my teeth into a character, a project. It really is my first love. The character that I portrayed was a minister, like my dad, but he was very different from my dad. My dad, whose name was Samuel, was actually more like Sammie [Miles Caton’s character in Sinners]. My dad was a trained opera singer and he wasn’t pushed out of following that path by his parents. He made that decision himself when he was called into the ministry. But he did have a huge appreciation of the arts, and he never tried to push me out of the arts, per se. Although he did say, “I’ll support you as an actor if you get a law degree,” with this idea of needing something to fall back on.

Well, turns out you didn’t need a backup plan! How long have you known Carlos for?

The first time I ever performed in LA, which must’ve been, like, 1998, the person who flew me out there to perform was Carlos Niño. I knew him as a young promoter, curator, and radio DJ. I eventually moved to LA in 1999 to record my first album and became friends with Carlos and his crew. That was the first crew I was introduced into in LA.

Was that the Dublab crew?

Exactly. Carlos, Frosty [Mark McNeill], and B+ [Brian Cross], but also Zack de la Rocha and all these cats who were in the underground music scene in LA at that time. Not everybody was necessarily underground—some of them were very overground. But either way, the music side versus the Hollywood side, I felt the difference. I moved out there to record my first album, but I’d also just released my first film and my representation was introducing me to all of the major players in Hollywood to see what I wanted to do to follow up Slam. That introduction into the Dublab crew gave me a grounding in a side of LA that I still appreciate to this day, as opposed to the actor side. I’ve always been on the music and poetry side of LA and that’s been nice.

Then, Carlos ended up putting together a number of shows in LA that I did in support of albums that came out. Of course, his own career was evolving into producing and making music as a percussionist and sound artist. He called me into the studio when he was working with André [3000], and I spent some time with them in the studio. When he was touring with André, I happened to be in Paris and came out to that show. Carlos and I spoke about making our own album, and that’s how the conversation began.

Did you know André at all before those interactions?

I had passing encounters with André through the years. Obviously, I was always a huge fan and he had paid me a major compliment the first time we met, which was around the time of “B.O.B.” We met backstage at a show and he told me that I was his favorite rapper.

“There’s oftentimes a sense of urgency that I’m playing with, and Carlos exhibits a kind of patience that’s really, really complementary.”

I knew that there would be mutual respect there.

Yeah. I was smiling for months after that. He’s obviously one of my favorite rappers. I’d started as a rapper myself and was really interested in evolving the art form surrounding the question of, “Where can we take this? Do we have to fit it inside of this rigid box of definition? Can we expand and explore while it’s still young?” That’s something that I feel like André always stuck to. He was always exploring—cadence, storytelling, flow, all of this stuff—as he continues to do now, being one of the first rap artists to produce a wordless album.

What did you discover about the music you wanted to be making with Carlos during that live performance?

The live performance was more connected to my background as a performer with years of touring, and from theater and improvisation. It reached a moment, with all that’s going on in the world right now, where I didn’t feel like anything was more relevant than just speaking directly to the moment and calibrating on the very day that we were performing it, based on what I had read in the news that day and what was on my mind. Feeling the energy of that space and what it is to be alive at a time when our government is so heavy handed in its pursuit of Palestinian death and in its imperial goals. For some, it’s a lot to wake up to, especially during that time period when Biden was in office and you had an overwhelming majority of people who were voicing opposition to what was happening and realizing that their voice didn’t matter at all. It was most important to just be in the moment on stage with Carlos.

What I appreciate about Carlos is that we have a balance, because there’s oftentimes a sense of urgency that I’m playing with, and Carlos exhibits a kind of patience that’s really, really complementary. What I found in this album—the one that will come out next year—is that it’s probably the recording that I’m most excited about in my career right now just because of its pacing. There’s something about having the patience to allow things to take their natural course, and that’s something that I credit Carlos with. If the song ends with a cymbal crash fading and it takes three and a half minutes for the sound to actually fade out naturally, he’s going to let it fade out naturally. FL