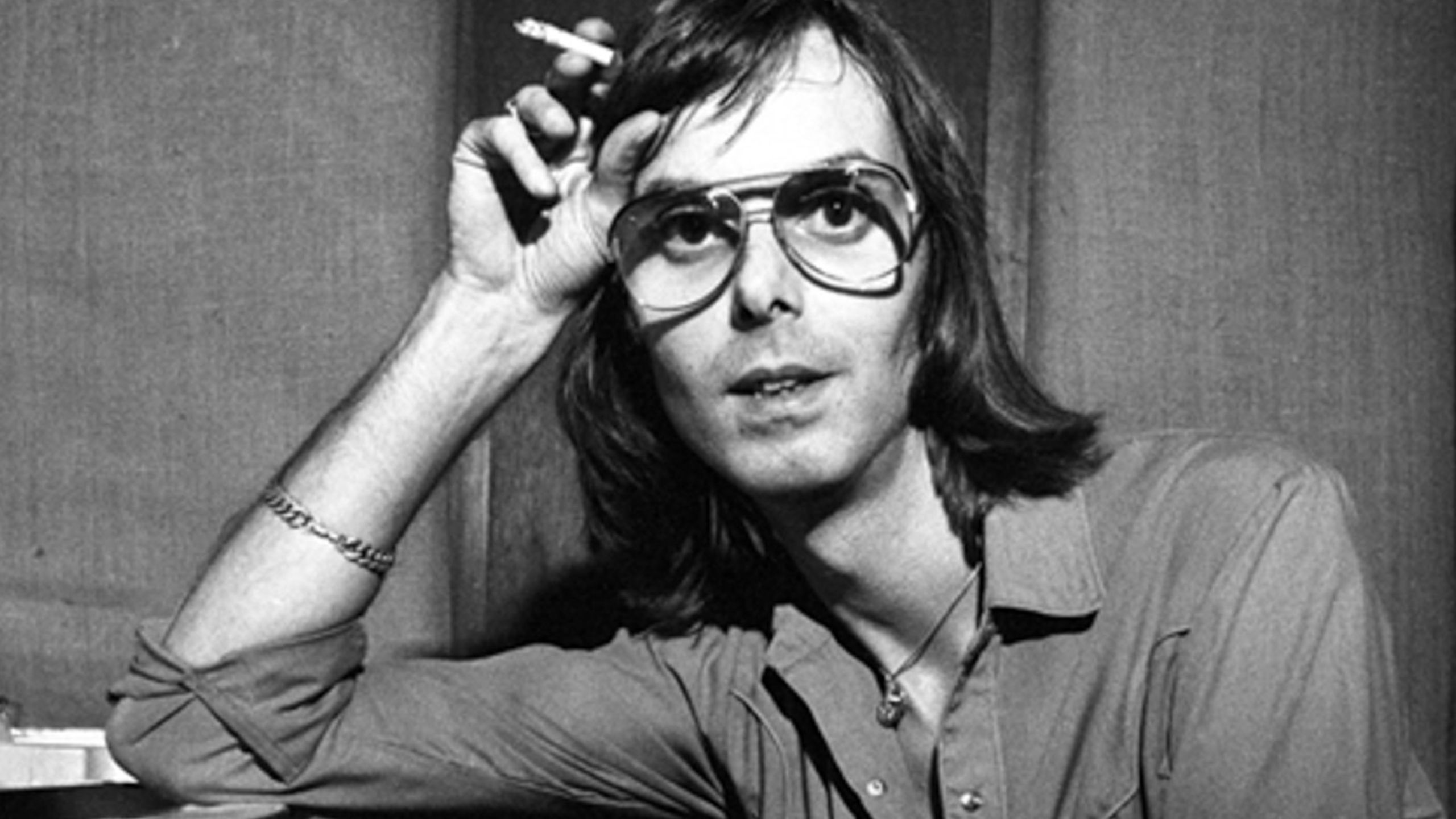

You may not have heard of Nicky Hopkins, but you’ve almost certainly heard him play. Arguably the greatest session keyboardist of the rock era, Hopkins’ colorful, propulsive, and often downright cinematic stylings enriched such classic tracks as The Beatles’ “Revolution,” The Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil,” The Who’s “My Generation,” and The Kinks’ “Where Have All the Good Times Gone,” and made an indelible mark on records by Jeff Beck, David Bowie, Joe Cocker, Donovan, Peter Frampton, Jerry Garcia, Art Garfunkel, Jefferson Airplane (whom he also appeared with at Woodstock), Carly Simon, Dusty Springfield, Cat Stevens, Rod Stewart, Frank Zappa, and many others, including solo recordings by all four Beatles.

And yet, Hopkins, who passed away in 1994 at the age of 50—and who will finally be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this week in the “Musical Excellence” category—is anything but a household name. This is partly because Hopkins did his greatest work in an era where session musicians were rarely credited on the records they contributed to, and partly because he was the sort of person who largely preferred to let his versatile musicianship do the talking. “He was a very quiet, background sort of guy, but a lovely person,” says John Wood, producer of the recently released Nicky Hopkins documentary The Session Man. “Everybody loved him as a person, as well as for his music.”

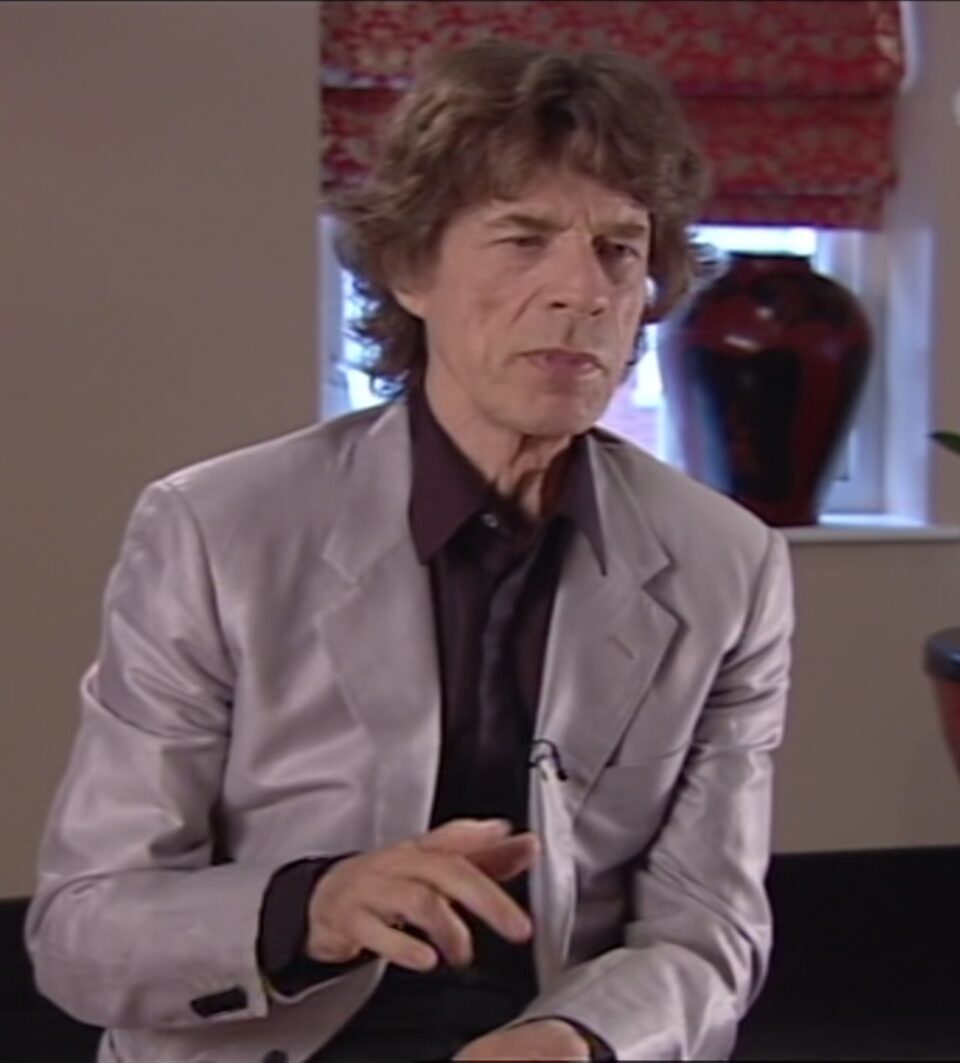

That sense of love and appreciation resonates throughout The Session Man. Seven years in the making, the film (directed by Michael Treen, who sadly passed away this past April) features commentary from Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Pete Townshend, Dave Davies, Peter Frampton, Glyn Johns, Jim Keltner, Nils Lofgren, Harry Shearer, Shel Talmy, and dozens of others who knew and worked with him, and who are clearly delighted to help shine a long-overdue spotlight on Hopkins and his unique brand of musical magic.

“He had a special style, a combination of gospel and classical that I never heard anyone else do,” recalls Jagger in the film, which also includes several informative segments where modern piano greats Greg Phillinganes and Paddy Milner pick apart some of Hopkins’ most iconic parts to demonstrate what made his playing so special. “He was so talented,” says Wood. “He could do anything; and if you were hiring him to play on your record, he could do exactly what you wanted, whatever style or feel. Somehow, he’d know almost instinctively what you wanted and where exactly to fit it into the song. And people told me that when he was there, they played better; he had a kind of a positive effect on their musical ability when he was in the room.”

“I just thought, ‘How come nobody’s heard of this guy?’ He’s worked with the biggest names in rock, played on some of the most important tracks ever recorded.” — John Wood, The Session Man producer

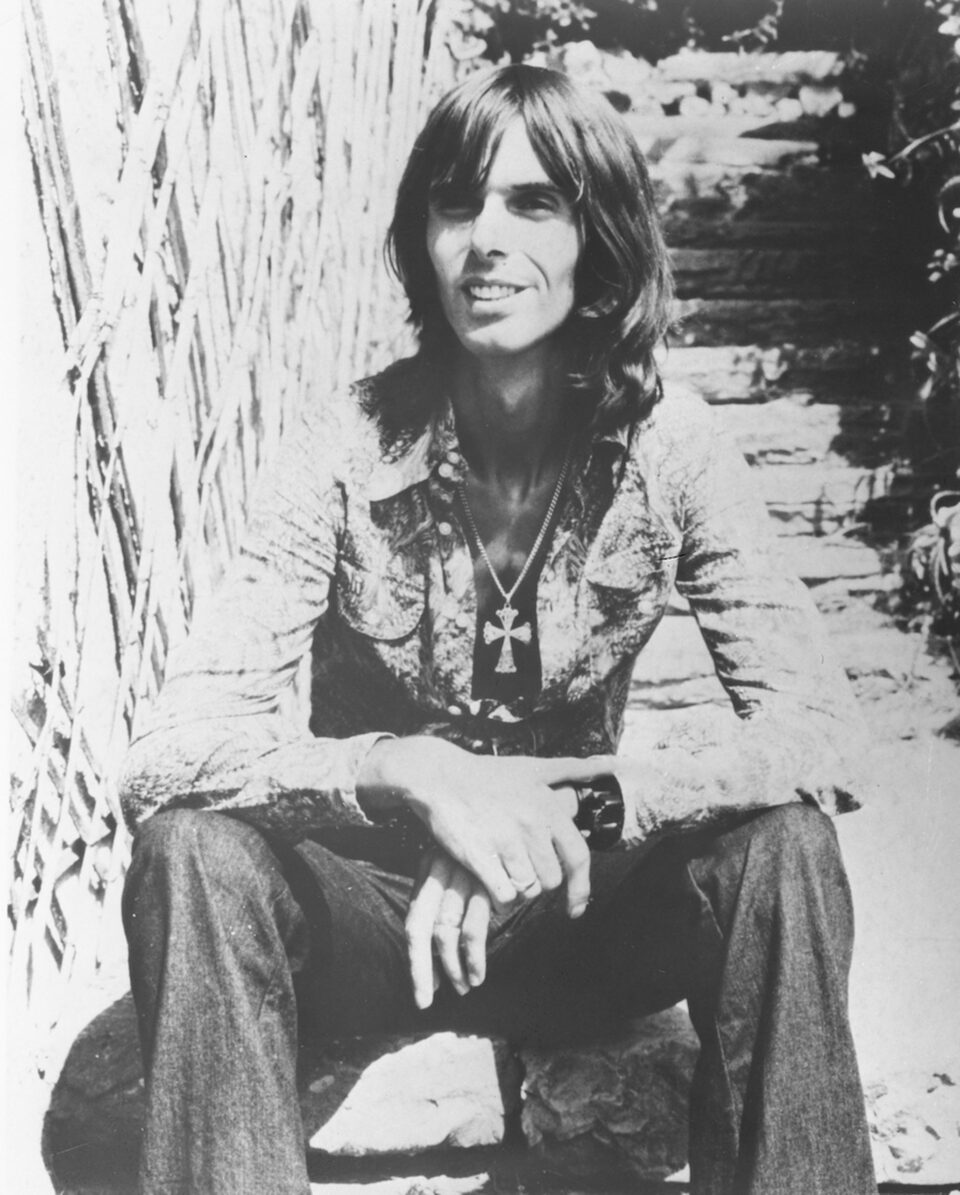

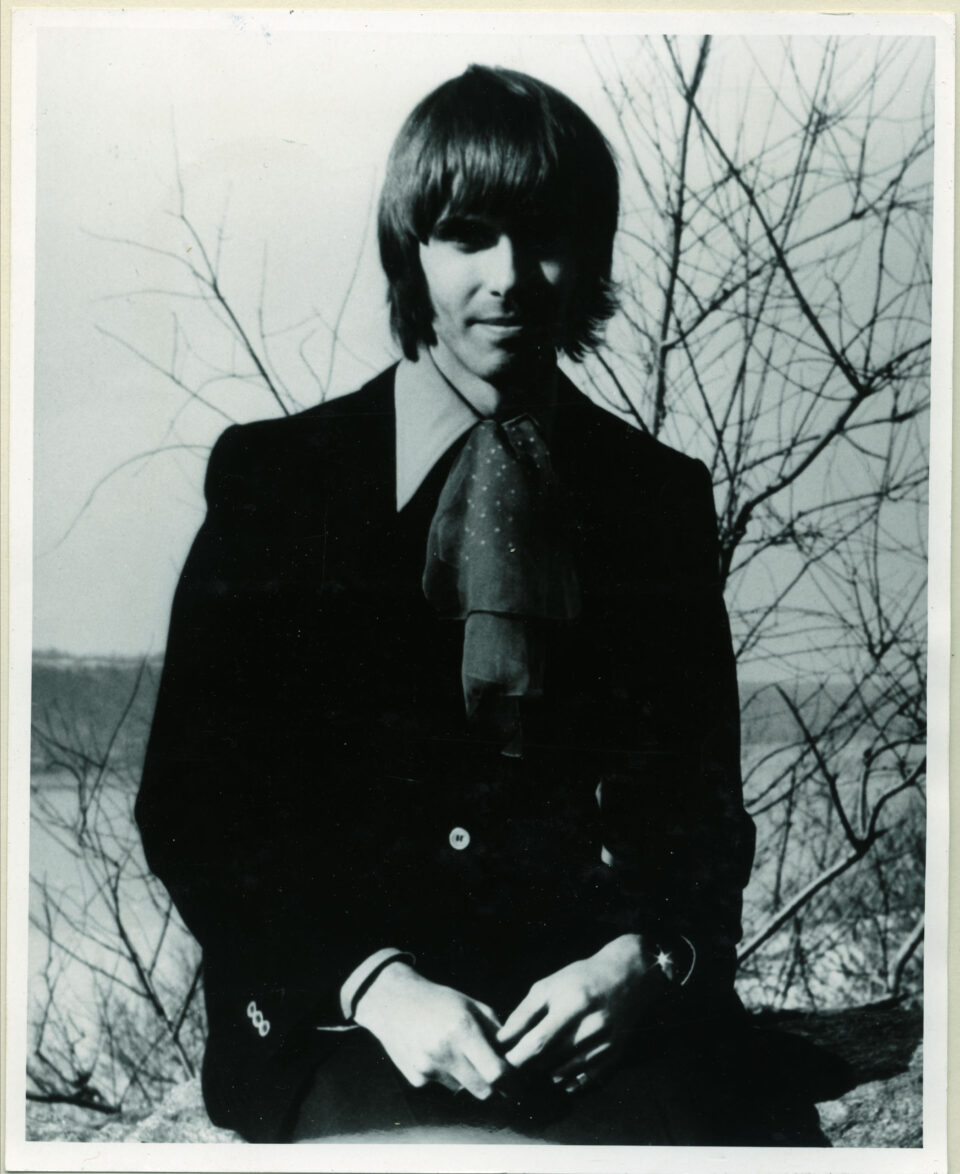

Born in the London suburb of Perivale in 1944, Hopkins began playing piano at the age of three. At 16, his prodigious abilities won him a scholarship to the prestigious Royal Academy of Music in London, though he soon ditched his studies to pursue his passion for rock ’n’ roll. After two years of touring with original British shock rocker Screaming Lord Sutch, Hopkins signed up with the blues-based Cyril Davies All-Stars. It was during the All-Stars’ sold-out residency at London’s Marquee Club that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards saw Hopkins in action for the first time. “Mick and I were down at the club to see Cyril, to see what his new band was like,” remembers Richards in the film, “and the piano player, he just blew us away. There’s this little white kid, and he’s sounding like he’s in the back room of somewhere in Mississippi or Chicago… Mick and I just looked at each other like, ‘Whoa, where did Cyril find this guy?’”

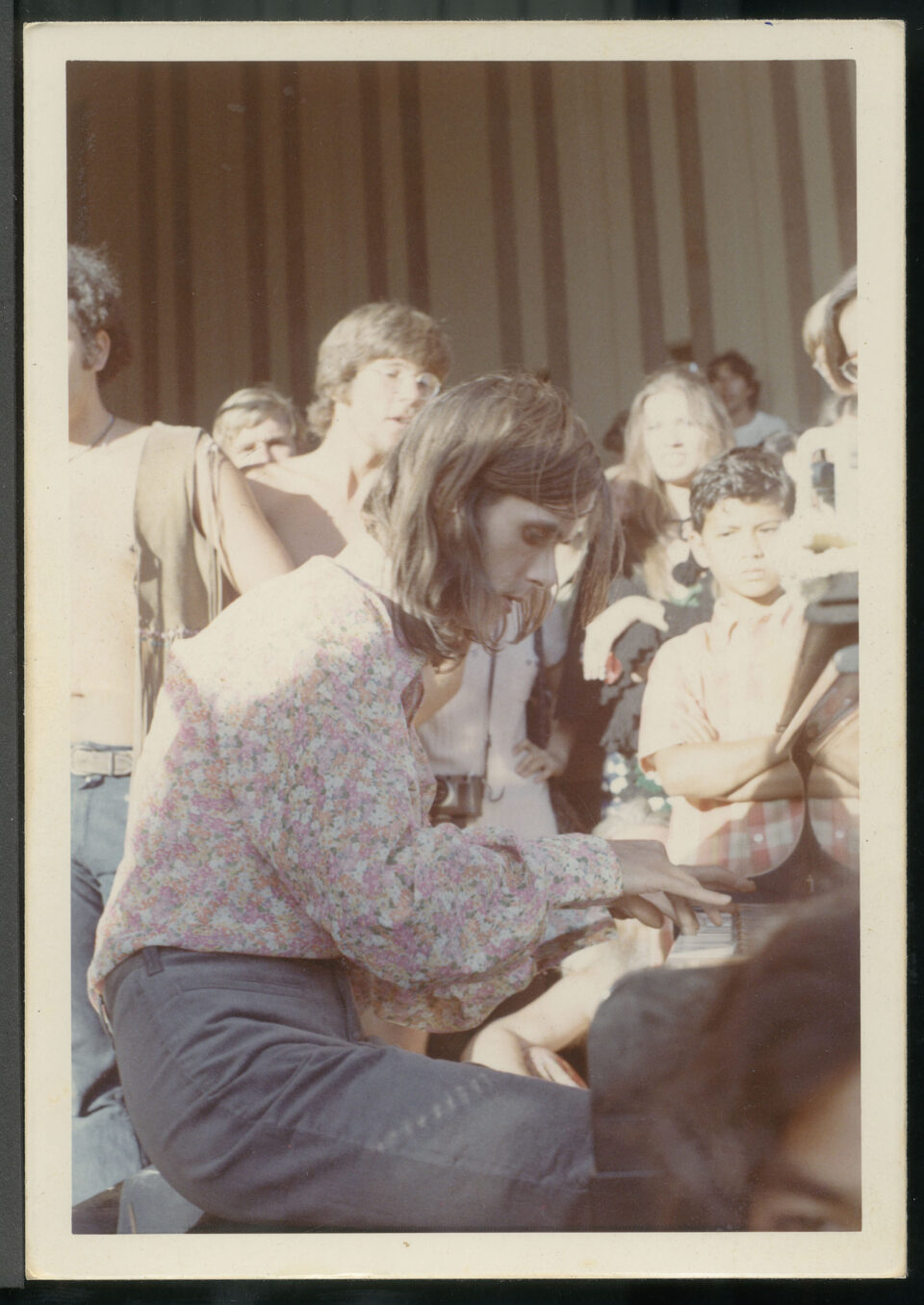

Unfortunately, as The Session Man reveals, Hopkins was a lifelong sufferer of Crohn’s disease. A particularly bad flare-up not only forced him to leave Davies’ band, but also led to a series of operations that left him bedridden for over a year and a half. Hopkins’ affliction forced him to come off the road and refocus on session work; and once producer Shel Talmy hired him to add an explosive boogie-woogie part to The Who’s 1965 hit “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere,” Hopkins quickly became the most in-demand keyboardist on London’s recording scene. Between 1965 and 1968, nary a week went by without the release of a new record featuring Hopkins’ playing; though rarely credited for his contributions, and sometimes not even paid, he nevertheless left a massive sonic footprint on the British pop music of the era, playing on such iconic albums as The Kinks’ Something Else, The Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet, and the Jeff Beck Group’s Truth. “It was kind of fortunate, in a horrible way, that he couldn’t tour during that period,” says Wood. “If he’d been a touring musician, we might not have gotten all these amazing recorded performances.”

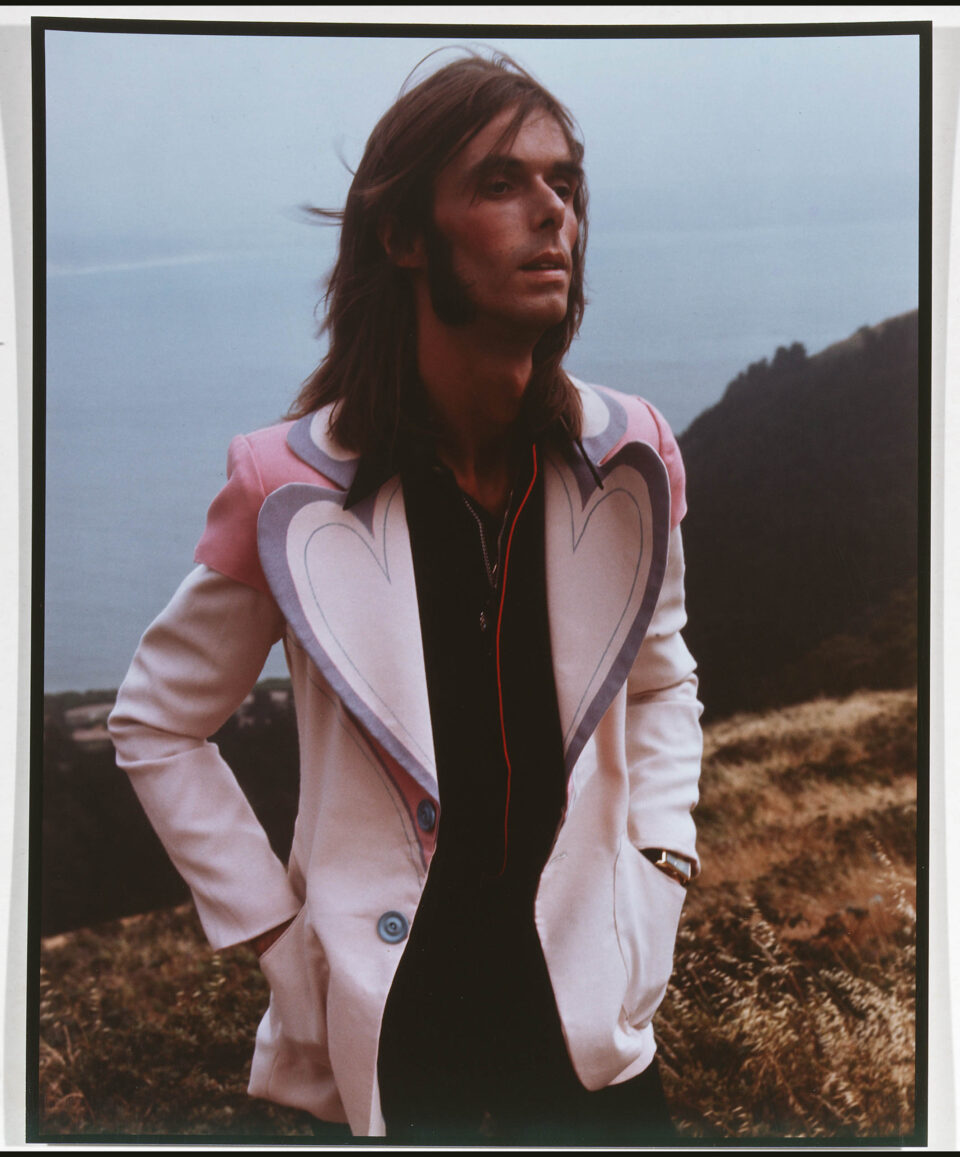

But in a surprise twist, 1968 not only found Hopkins going back on the road (this time with Rod Stewart and Ron Wood in the Jeff Beck Group), but also falling in love with both the Bay Area and its psychedelic music scene. The San Francisco groups embraced him in return, and Hopkins soon became an integral part of their scene jamming and recording with Jefferson Airplane, Jerry Garcia, and Quicksilver Messenger Service. Though he relocated to Marin County’s Mill Valley, he continued to fly back to the UK in order to work on albums like John Lennon’s Imagine, The Who’s Who’s Next, and George Harrison’s Living in the Material World.

Hopkins also continued to work with The Rolling Stones—with the exception of Some Girls, he appeared on every Stones album from Their Satanic Majesties Request through Tattoo You—and toured with them on several occasions, though his health issues ultimately became too much of a liability for the band. “They said, ‘We can’t take you out with us, because we’re worried that you’ll have to be hospitalized, and suddenly we’ve got no keyboard player,’” Wood explains. “I suppose that could happen to anybody, anytime, on any tour, but it was obviously much more likely for him.”

Hopkins’ increasing addiction issues—which The Session Man doesn’t shy away from discussing—rendered him an additional liability as a touring musician. “He was constantly in pain from Crohn’s disease,” says Wood. “He would use all these medications, prescription, or street drugs, whatever, just to dull the pain. He wasn’t outrageous or did terrible criminal things, but he very nearly died from it.”

“He had a special style, a combination of gospel and classical that I never heard anyone else do.” — Mick Jagger in “The Session Man”

Thankfully, Hopkins was eventually able to kick his addictions during the 1980s, a decade which also saw him marrying his second wife, Moira Buchanan, with whom he shared what was by all accounts a happy existence before Crohn’s complications finally felled him in September 1994. But while Hopkins’ death was widely noted at the time in music publications around the world, awareness of his legacy seemed to fade over the ensuing decades. Which is why Wood felt that a documentary about him needed to be made. “I just thought, ‘How come nobody’s heard of this guy?’” Wood explains. “He’s worked with the biggest names in rock, played on some of the most important tracks ever recorded in rock history, and made them sound fantastic, and no one knows his name. I mean, obviously the hardcore fans and musicians know him, but the general public have no idea who’s playing the piano on ‘Angie,’ you know? They don’t even question it. I always felt that was wrong, and I just really wanted to right that wrong.”

In 2019, Wood—a social media consultant by trade—successfully raised money to have a piano-themed bench installed in Perivale Park in celebration of what would have been Hopkins’ 75th birthday. He also raised funds to create a scholarship in Hopkins’ name at the Royal Academy of Music and successfully lobbied the Ealing Civic Society to put a plaque on Hopkins’ childhood home. But when Graham Parker (who’d enlisted Hopkins to play on his Another Grey Area album back in 1982) suggested that a documentary film would be the best way to spread awareness of Hopkins’ contributions, Wood sought the counsel of one of the few people he knew with connections in the film industry—British character actor and voice coach Valentine Palmer, who in turn introduced him to TV producer Michael Treen.

Treen and Wood shot their first interviews for the project in November 2019, and the momentum for the project built from there—and the project, in turn, helped to push Hopkins’ candidacy for induction to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. After several letter-writing campaigns from fans failed to move the needle, Wood got a connected friend to send a direct email to John Sykes, the Chairman of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Foundation, asking if he thought Nicky Hopkins should be inducted. “Believe it or not, he replied,” Wood laughs. “And he said, ‘Oh, you don’t have to tell me how important Nicky is; I’ve been a fan of his since I was a teenager!’”

Sykes suggested that the best way to promote Hopkins’ candidacy was to harness the support of the musicians he worked with—and, thanks to their work on the documentary, Wood and Treen had already forged connections with several dozen of them. “I wrote to 52 people about it,” Wood recalls, “and I got 52 responses, either emails, signed letters, or videos, all of them gushing, saying, ‘Of course, he’s the greatest!’ I had a video from Ronnie Wood saying, ‘Come on, he’s the man!’ And signed letter from Keith Richards, signed letter from Rod Stewart… I sent it all to John Sykes, and he was like, ‘Wow! Now I just have to get it past the committee!’”

Finally, the Hall announced this past April that Hopkins would be inducted for 2025, along with such diverse luminaries as Soundgarden, OutKast, Cyndi Lauper, The White Stripes, Warren Zevon, and—coincidentally—Joe Cocker, who Hopkins had recorded and toured with. “I was on the edge of my seat waiting for the announcement,” Wood remembers. “Finally, the email came: ‘He’s in!’ It was 3 a.m. and I was about to get on a flight to Germany; I was so bleary-eyed, but I’ll just never forget that moment. And it’s been crazy ever since—Variety, People, Rolling Stone, they’ve all been running news of the 2025 inductions, and Nicky’s mentioned every time.

“So what I wanted, which is to get him known, is really happening,” Wood marvels. “And the snowball is just getting bigger and bigger. The Rock Hall is the sort of culmination of all this work; I couldn’t have planned it better, but I didn’t really plan it at all!” FL