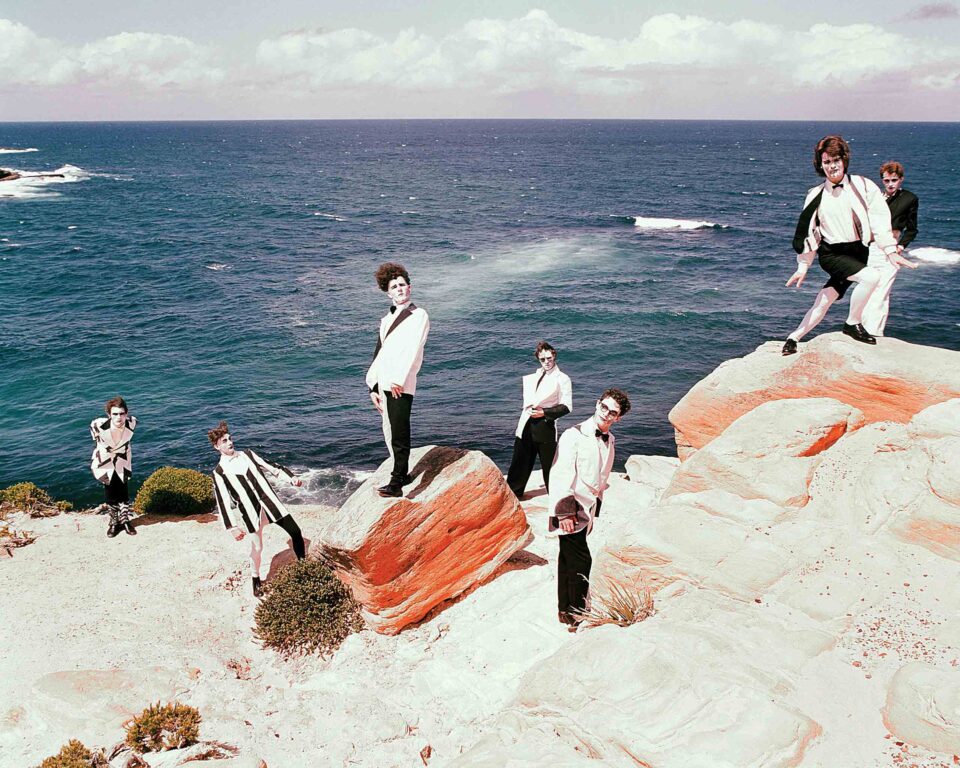

Best known for the hit “I Got You” in 1980 during the peak of the new wave movement, New Zealand’s Split Enz are a revolutionary band who, despite an unconventional approach to making music, became a standout attraction Down Under before going abroad. They wore eye-popping costumes designed by percussionist Noel Crombie, and the six members twisted their rollicking music into a unique sound. Founded in 1972 by co-frontmen and songwriters Tim Finn and Phil Judd, the group established themselves as an oddball outfit with a somewhat spooky vibe. They were like a ship sailing to different musical ports—prog, psychedelia, folk, ragtime, and beyond—and cross-pollinating them. The music could be upbeat and eerie at the same time.

By 1976, they emigrated to England where they gigged in the bustling pub-rock scene. Judd would depart in 1977, and Finn’s younger brother Neil (future leader of Crowded House) came onboard as co-frontman and songwriter. The group grew in stature, but by 1984 they called it quits with their ninth album See Ya ’Round. Along the way, they charted three albums at #1 back home, developed a strong Canadian fanbase and cult American following, and toured internationally. After disbanding, Split Enz reunited every few years until 2009, and next year the group will be returning to play shows in New Zealand and Australia to arena and festival-size crowds.

A robust document of how this quirky, original group started, their new five-disc box set ENZyclopedia Volumes 1 & 2 collects their remastered 1975 debut album Mental Notes and its 1976 follow-up Second Thoughts, alongside demos and live cuts, to provide an in-depth chronicle of their musical genesis (keyboardist Eddie Rayner’s remix of their second album is also included). Finn recently sat down with us to revisit that era of the band and their inner workings as they went from idealistic young musicians into a well-oiled and genre-bending outfit.

It feels like Split Enz developed its own musical personality very quickly.

It literally started with me and Phil and two acoustic guitars—I can vividly remember writing those first two songs. We were about 19 or 20 when we started trying to write our own songs, although I had written previously at school with Mike Chunn who ended up being Split Enz’s bass player. When I started writing with Phil, something really special happened between us. We believed in these songs and thought we’d entered the hallway—at least the antechamber—of the greats. As it turned out, it wasn’t going to be a smooth ride.

When I hear some of the early stuff like “129” and “Sweet Talking Spoon Song,” I get an early 20th century American vibe to a lot of it. The first album has “Under the Wheel,” which is trippy and epic, then the moody “Spellbound.” There’s also a goth sense of theatricality that went along with the performances.

I get what you mean about early 20th century American music [with “Sweet Talking Spoon Song”]. I also think it has a music hall or a vaudevillian feel, influenced to some degree by the Small Faces, who were never shy about pulling that in—those layers of English language and accents and style and attitude. But then all those English bands were influenced by American music. We weren’t really that schooled in those connections when we were young. New Zealand radio didn’t play very much of a range—whatever was pop and on the charts.

The more gothic and sprawling arrangements that we got into were very much part of what the band did in rehearsal. We had great rehearsals. We all respected each other, admired each other. I look up to these guys because they were at art school. These guys were hardcore, they had no problem believing in themselves as artists. That’s what they were, and I’d never met people like that. So we’d get in a rehearsal room, and everybody would be trying to impress each other. You’d get to a part of a song and we’d just sit there playing chords and grooving out. Somebody would come up with a motif, and it just grew out of mutual respect and love for each other and interest in music.

“When I started writing with Phil, something really special happened between us. We believed in these songs and thought we’d entered the hallway—at least the antechamber—of the greats.”

Don’t forget, the Eagles were the biggest band at the time, and that kind of soft rock coming out of California. We didn’t like the Eagles. We liked Bowie and early Roxy Music. But the music coming at us through radio wasn’t really what we were trying to do. We would keep the ’60s flame alive. Once you’d heard “I Am the Walrus,” you couldn’t just write a normal song.

Phil Manzanera produced your second album after he watched you open for Roxy Music, correct?

Yeah. We were in Basing Street Studios making the album with Phil before too long, and there was a huge investment at that point in the band [from their Australian label Mushroom Records]. We didn’t have a label deal internationally, and we didn’t even have an agent. We got Chrysalis down to watch us—they put us on a bill with Gentle Giant in Southampton. Terry Ellis and Chris Wright saw us and loved it and signed us. So at that point Michael Gudinski [who signed them to Mushroom] was sailing, he was home free. It was a leap of faith. He watched us in Sydney in a pub, and he had Skyhooks at the time, the biggest band in Australia. It was a maverick move [to sign us]. We were not radio, we were not commercial, we were very idiosyncratic, but he just loved it. I don’t know if that happens anymore.

Were Bob Marley and the Wailers in an adjacent studio at Basing?

We were upstairs in the main room, and they were down [in the basement studio] making Exodus. So history was being made. We didn’t know anything about reggae music at the time. There was just this amazing bass sound coming up from the room when they opened the door. We thought, “Wow, we’ve never heard anything like that before.” We were always obsessed with trying to get more bottom end on our records. It was the hardest thing to get, and there it was just pouring out of the door.

When you went back through these early tracks, were there things that were buried in the mix or stuff you guys had forgotten about that was brought to the forefront?

One thing for sure is that there was a lot of percussion that had been buried in the mix, or often left off completely. [Eddie Rayner] was rescuing very idiosyncratic percussion tracks that don’t play all the way through the songs, but they just erupt every now and then. That was Noel, of course. Mixing people in those days didn’t know what to do with him. You listen to [1980’s] True Colours—there’s no percussion on the whole record, hardly, and yet he played on every track.

“We had great rehearsals. We all respected each other, admired each other... These guys were hardcore, they had no problem believing in themselves as artists.”

I’ve heard the Australian pub-rock scene back then could be brutal. You had to really entertain people or they would throw things at you.

We did get things thrown at us. There were some very memorable shows where we were put on the bill with hard-rock bands. We played on a bill in Melbourne in 1975 with AC/DC and Skyhooks. Bon Scott flew out over the crowd hanging on a rope dressed as Tarzan. It was pretty exciting. But AC/DC fans absolutely hated us, so we got booed and cigarette butts and beer cans [thrown at us]. But the pubs were not as rough in terms of people throwing things. You’d be met with indifference, but there’d always be a cluster of obsessed people. I think they were Bowie fans, Roxy Music fans, and they’d been waiting for a band to come along that just had some of that drama and intrigue and multi-layered approach. We had about six or seven fans that came to every single show, and we’d go, “Oh, the ghost girl is here,” or, “The twins are here.”

Was Noel doing costumes from the outset?

Around ’74 is when he turned up one night in Hamilton, a small city about 100 miles south of Auckland where we were all living. He had one of those lovely antique suitcases with all these clothes inside it. We loved them, and took them out and wore them. And that was that. We joined Noel’s universe. Noel also joined the band without being asked, or us even thinking about it. He came out one night playing spoons, and it was so great and the crowd went nuts. The next minute, he’s in the band. So he’s a very enigmatic character. He wasn’t hustling or pitching himself, he just did what he did, and it was obvious he should be in the band. Then, gradually, he started playing percussion.

Are there any early Split Enz songs that have major personal significance for you?

I would find it really hard to pick out anything, really. Eddie and I did a project called Forenzics where we took little pieces of [those] songs and looped them and wrote new songs over them—new melodies, new lyrics. It was interesting to go back and find those little pieces that we’d labored on. We started with the one that was from “Walking Down a Road” and just went from there. That was when the past became more interesting to me. In that sense, I really got a lot out of it. It wasn’t nostalgia. It was ever-present, ever-alive, and all the songs can do if they hit you at certain moments, certain days.

When your brother Neil came into the band, that injected a different flavor. A lot of people have noticed that a lot of the great stuff you did came near the end of your time with the band.

It’s always so great to have two writers in the band. We hardly ever wrote together, which is interesting because subsequent records we made—like the Finn Brothers records and the Woodface album—why didn’t we do that when we were actually in the band? Why didn’t Eddie and I write more songs? It’s so weird to me.

Is there anything we should know about the reunion tour? Will there be any deep cuts? Costumes?

There will be new clothes. We’ll be doing some deep cuts on the May tour. We’ll be looking at doing two or three songs from Mental Notes. It’ll be a great tour. FL