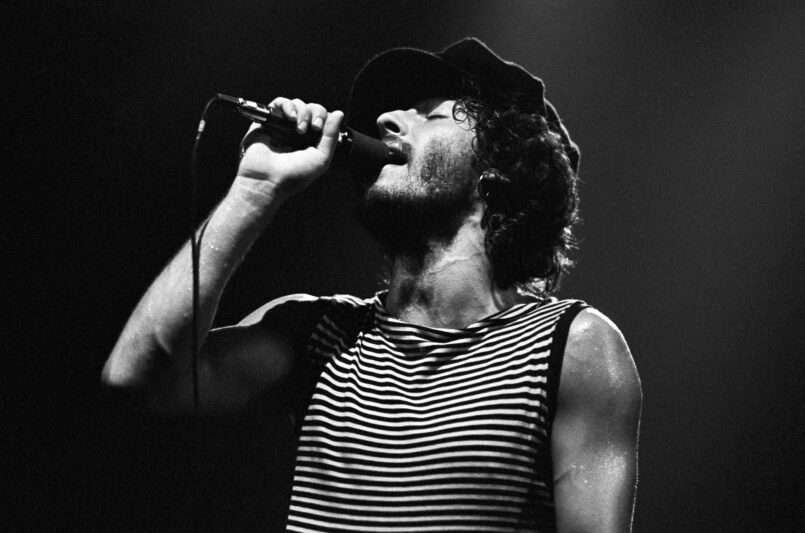

Forty years ago today, an up-and-coming singer-songwriter with a bad beard and a collection of poorly fitting knit caps released one of the grandest statements in the history of rock and roll music. Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run is an overwhelming statement of love and possibility built with confidence on the tenuous idea that a great rock and roll song and a pretty good car are all you need to get away from your troubles. It’s the ultimate teen fantasy painted broadly with chunky guitars and heavy sax, songs that fall over themselves with joy and collapse into romantic exhaustion. There is no rock and roll record more concerned with the idea of being a great rock and roll record.

On the occasion of Born to Run’s fortieth anniversary, we asked our staff to take a closer look at each of the album’s eight tracks. Strap your hands ‘cross our engines and come along.

Click here to listen along on Spotify.

Side One

1. “Thunder Road” — I’ve been listening to “Thunder Road” for thirty years, and it still mystifies me. Does Mary get in the car? Does he get out of the town full of losers? Does he win? In 1975, I think Springsteen would have said “Yes,” “yes,” and “indubitably.” When I turned twenty-two, I wrote “So you’re scared and you’re thinking that maybe we ain’t that young anymore” on my wall, so that my mind would automatically tell itself “Show a little faith, there’s magic in the night” every time I glanced up. Which is maudlin and goofy, but it’s also the kind of thing that would happen in a Springsteen song—an anonymous, purposeless youth turning to a rock and roll cliche to get through a rough patch. Bruce didn’t believe in this kind of thing for much longer—it’s love and faith that save him three years later in “Badlands,” and by the time he released Nebraska in 1982, he was actively writing against the idea that a great song could effectively change your life. I tend to agree. But I’m still listening to “Thunder Road.” — Marty Sartini Garner

2. “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” — If “Thunder Road” is the last-ditch escape from the town full of losers, “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” is the arrival in the big city—and the subsequent realization that arriving somewhere is one thing, but surviving is a different beast altogether. Kicking off as all groovy goodness on the surface, the song is like if Bruce stumbled into a party on Tenth because it sounded fun from the street, but then found out the hard way that you can’t just pull that shit outside of Freehold. Horns blasting, piano dancing—the party is still going on in most of the room—but in a corner, The Boss has his back to the wall, and is grinning that goofy-ass smile of his as his last card to play. Good thing The Big Man showed up just in time. — Nate Rogers

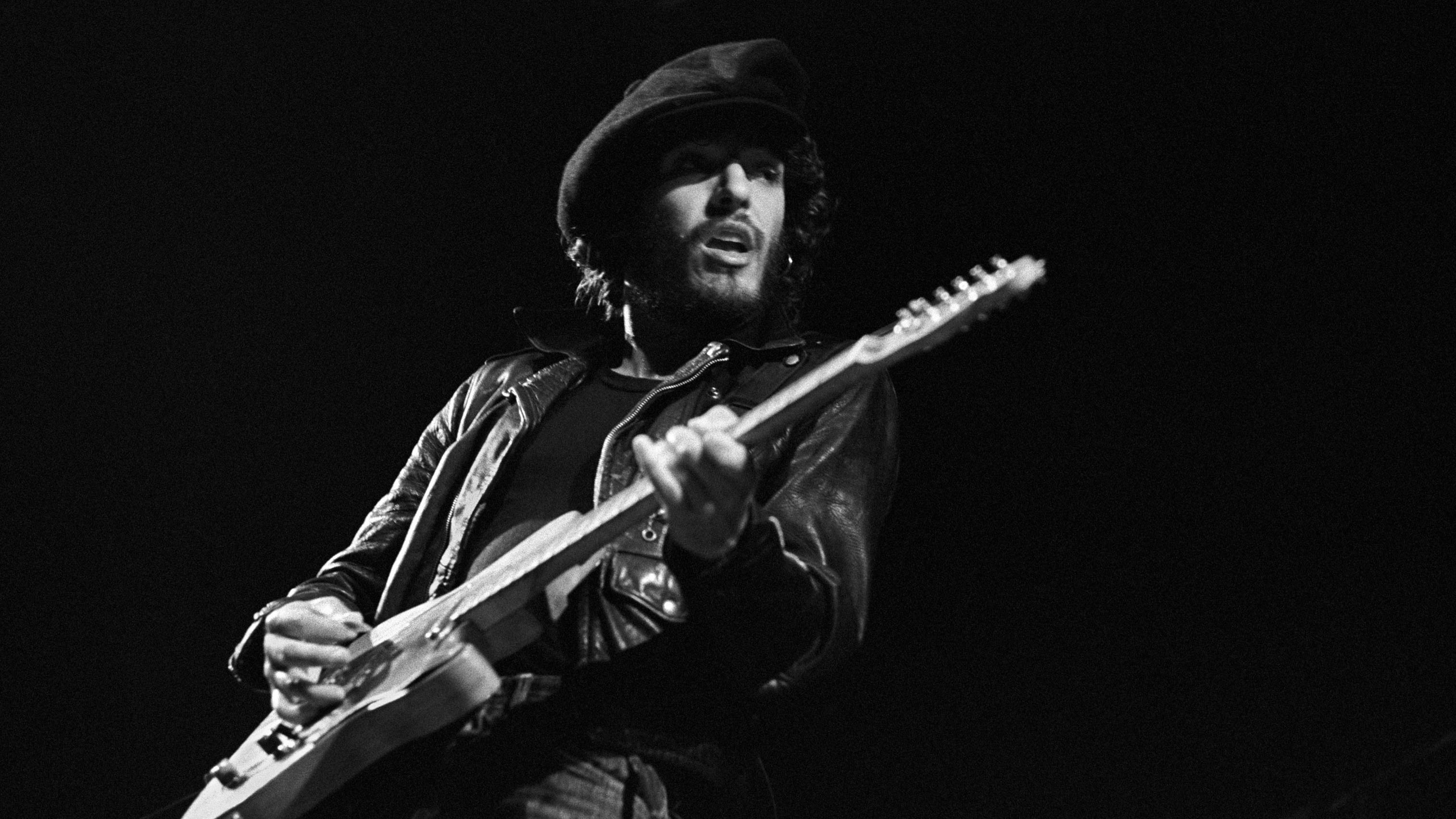

Bruce Springsteen performs with The E Street Band at Alex Cooley’s Electric Ballroom on August 22, 1975 in Atlanta, Georgia. / photo by Tom Hill/WireImage/Getty Images

3. “Night” — Beginning with Max Weinberg’s scattergun, statement-of-intent drumming and routing its struggles through The Big Man’s blaring sax, this is the song that turned Springsteen from skinny troubadour into The Boss. Maybe that’s because it’s the first time he uses the phrase “boss man” in describing the blue-collar character’s love of cars and drag racing—a constant theme—or because it moves away from the lengthy, drawn out jams of his first two records (and, for that matter, the track directly preceding it) onto a tighter, heavier edge. “Night” is one of the first Springsteen songs to deal with the workingman theme that he became widely known for years later, but it also echoes the youthful exuberance of the exciting moments of his early career. Propelled by Garry W. Tallent’s underrated bass line, the song remains a fan favorite, even though it’s been played only sporadically live over the years. — Daniel Kohn

4. “Backstreets” — Born to Run is the score to the musical never made about living in New Jersey, and “Backstreets” is its finest six and a half minutes. It’s as unabashedly theatrical and bombastic as the rest of the album, but somehow quieter, more serious. The stakes are as high and as low as they can get as the whole city cries for itself and its youth, who are slow dancing drunk at the beach. When the song crescendos for the first time with endless juke joints, some of those dancers are hurt bad, and some are really dying. What’s the difference—and is this all there is? This is the crux of the song and of the album. If they’re born in fire, born to run, the simultaneous necessity and hopelessness of life in “Backstreets” is what finally makes stranded would-be heroes like Terry come out of hiding and do so. — Lydia Pudzianowski

Side Two

1. “Born to Run” — In 1978, Bruce Springsteen showed up on “Slipaway,” the third section of Lou Reed’s grim and haunting rock opera Street Hassle, quietly rapping: “It’s a song lots of people know, it’s a painful song, a little sad truth, but life’s full of sad songs…y’know tramps like us, we were born to pay.” Street Hassle feels like the antithesis of “Born to Run,” Springsteen’s triumphant, B-movie fantasia, buoyed by The Big Man’s pealing sax and the E Street Band’s Wall of Sound, but it was born from the same kind of desperation Reed sang about. It was Springsteen’s big gamble on a hit after two flops, taking a grueling six months to finish. With its ripped bones and lonely riders, it’s a painful and sad song, but even more, it’s one “lots of people know,” about teenage lust, cars, fragile masculinity, and America. It was a hit—a massive one—but even more, it was an anthem for tramps born with a debt too high pay, whose only option was to leave it in the rear view. — Jason P. Woodbury

2. “She’s the One” — It took diving into the depths of his soul for The Boss to figure out how to properly follow up the untouchable anthem “Born to Run.” He had to dredge up a personal ghost, a lost love, to haunt him all over again. “Professor” Roy Bittan sets a light mood with a piano riff that twinkles under Springsteen’s growling vocals. He’s seared with pain and disillusionment as he launches into “She’s The One.” The ache is palpable as Bruce pleads, “I wish she’d just leave me alone.” Springsteen’s vivid imagery of “French cream” and a “heart of stone,” indicate just how drawn to this alluring flame he is: “But there’s this angel in her eyes / That tells such desperate lies / And all you want to do is believe her.” Is this a song about the one that got away or one that never was? In the end it doesn’t matter because, to The Boss, “She’s the One.” — Jay Pennick

Springsteen believes in nothing if he doesn’t believe in the potential of the self.

3. “Meeting Across the River” — There are two sharp edges to Randy Brecker’s trumpeting clarion call that stream through this illusive dream of a tune. The first is hopeful. The second is utterly haunting. Dreams do that. They can carry, and they can crush. But Springsteen believes in nothing if he doesn’t believe in the potential of the self, and here he throws down his sympathies for a lonesome figure gazing up from the banks of Jersey at the jazzy city lights of Manhattan, so far off and still so in his face day after day. Darkness lays across this distance. Starving for purpose and pride, is his flawed hero looking for a score? A job? An audition? Doesn’t matter. He’s man in over his head and desperate to prove himself. This is a melancholic meditation on last chances, where the Hudson might as well be the barrier to another world. — Jeffrey Roedel

4. “Jungleland” — How do you close an album that has so many hits on it? With an almost-ten-minute epic tale of restlessness and working class life. “Jungleland” is the fitting finale of Bruce Springsteen’s blue-collar fairytale because all dreams—even ones about far-off adventures and damsels in distress—have to come to an end at some point. By the time the idyllic first verse concludes (“Barefoot girl sitting on the hood of a Dodge / Drinking warm beer in the soft summer rain”), The Boss shifts gears—turning up the drama and the amps. It’s easy to put Born to Run’s eighth track in that easily defined box of adolescent anthems, but in reality, “Jungleland” takes listeners on a chaotic journey of fear and apathy in the face of death and despair. He compares guitars to weapons and calls bands “midnight gangs,” so by the time that someone actually loses their life within the song itself, there’s no shock in his gruff voice, just fatigue. Springsteen ends “Jungleland” with no words, just a single and powerful cry. After forty minutes of poetic lyrics and visions of a better life, there are no words to accurately describe disenchantment. — Bailey Pennick