In 1978, John Lydon emerged from the gob-and-drug-strewn trash heap of the Sex Pistols. He was a singular talent, determined to put the cynicism of his former band to bed. Johnny Rotten was dead. Long live John Lydon. Long live Public Image Ltd.

Lydon formed Public Image Ltd. (PiL) almost immediately after the Sex Pistols disbanded. As far ahead of their time as the Pistols were in creating brutal, stripped-down rock, PiL were equally forward thinking in the early days of post-punk. Innovative, bass-heavy, experimental, even musical, the band came together in a mad scramble, and before 1978 was out they had a debut LP, Public Image: First Issue.

PiL worked hard for fourteen years, releasing eight albums that charted surprisingly well in the UK before breaking for a decade and a half to work on various side projects. Back at it in the late aughts, and famously bankrolled from the proceeds Lydon made from a television commercial for UK butter brand Country Life, the group re-formed to release 2012’s This Is PiL. 2015 marks the forty-year anniversary of the Sex Pistols’ formation and will coincide with the release of PiL’s What the World Needs Now… On the eve of the new album, FLOOD called up the mercurial artist behind both bands and tried to get him to stay still long enough to tell us about Public Image Ltd.’s early catalog.

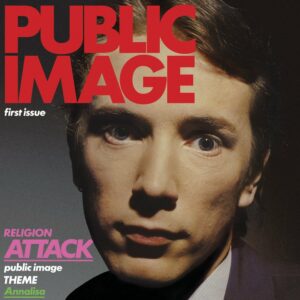

When I say Public Image: First Issue, what does that bring up?

Well, the first single, the “Public Image” single, came from a beautiful little guitar part Keith [Levene] was haphazardly playing in early rehearsals. It was a joy to find that I had this other voice and could express the sentiments so fluently. We were focusing really on rhythm and guitar—you know, that resonating guitar thing that we loved so much. And of course, there are songs on there that are very brittle and angst ridden, like “Annalisa,” which is a joy to behold but very difficult to sing.

You were coming right off the madness of the Pistols, so it must’ve all flown into that.

Well, I had songs in my head, so I was very eager to get back to work. When we got the opportunity to do that, we did it.

Metal Box [Second Edition in the US] (EMI, 1979)

Metal Box [Second Edition in the US] (EMI, 1979)

And pretty quickly after that, Metal Box came out.

Metal Box was great fun to make. Very difficult because the money wasn’t there to pay for recording studios, so we went in on the spare time between other people’s sessions—usually beginning after midnight and ending at 4 a.m. It sounds like a very cohesive album, but the way we put it together was very random.

The Flowers of Romance (Warner Brothers, 1981)

The most fabulous record to make was The Flowers of Romance, which was very difficult because when I got out of jail [Editor’s note: Lydon served time for a weekend after a pub brawl in 1980], I wanted to rush back into the studio, but I couldn’t get anyone interested. The drummer at the time, Martin [Atkins], booked himself with his [other] band to tour America. I got a few drum loops out of him. Keith was disinterested, so I basically had to fiddle around a lot on my own with things. The townhouse studio we were using at the time wasn’t fully complete, so they hadn’t put the carpets on the walls. It had a wonderful church-like echoey quality,which I still strive for to this day.

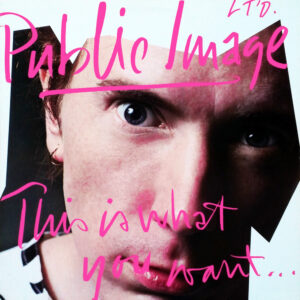

This Is What You Want…This Is What You Get (Virgin/EMI, 1984), Album (Elektra, 1986), Happy? (Griffin, 1987)

This Is What You Want…This Is What You Get (Virgin/EMI, 1984), Album (Elektra, 1986), Happy? (Griffin, 1987)

Those three records all came out very quickly.

With very, very little record company support. We had to raise the money from live performances, which is what we do now. We don’t have to listen to people telling us what we should or shouldn’t be doing. Once that obstacle is removed, the financial woes don’t seem so relevant. It’s very hard to endure the two things at the same time.

What was the thought behind Album?

To avoid commercialism by all means necessary by adopting the most commercial thing I have ever seen in American supermarkets. It was just the product name on it.

The generic cigarette packaging on the cover.

I thought it was really funny. And so I adopted that wholesale to the point where I didn’t mention who was on the album. Elektra didn’t get the joke. It came straight in at number eighty-seven on the American charts—I remember this. And they withdrew it.

It was a Top 20 record in the UK as well.

Two hours after that I informed them who was actually playing on it: Ginger Baker, Steve Vai, Ryuichi Sakamoto.

And then Happy. Was Happy, happy?

I can’t remember the producer’s name off the top of my head [Editor’s note: Gary Langan co-produced the album]. Damn. It was an album where he wanted me to find different ways vocally to twist the lines. I became so deeply entrenched—I don’t let no one tell me what to do. I should’ve been smarter about it and realized he was trying to help me.

[9 co-producer Stephen Hague] was great. These are good producers. You run into problems when they try to dominate and turn it into their sound. The biggest poison was Steve Lillywhite. Several years earlier he tried to come on board with things. Said we couldn’t have that much bass on an album. Well, you know what? Yes we can. So I lowered the vocals. To me it’s the overall tone and texture of the thing.

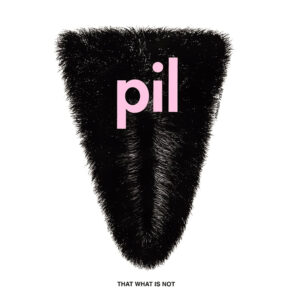

That What Is Not (Virgin, 1992)

That What Is Not had that sample of “God Save the Queen.”

Oh, you’re talking about “Acid Drops.” I used a reference to it at the end. I love [“Acid Drops”], by the way. I thought it was really poignant at the end of it. [It and “God Save the Queen”] are both references to the future. If you don’t fucking start thinking about it.

That record did kind of spell the end of a period. Did you feel that hiatus coming on?

I didn’t like it. It stifled me. I felt like I was being censored for all the wrong reasons. There were an awful lot of bands using PiL ideas at the time. They were being backed fully by my own fucking record label. It was infuriating but, you know, I bit my tongue and took a deep breath and persevered.

A lot of complicated issues were developing in my personal life at that point, too. We had to look after Ariane [Forster, The Slits’ Ari Up, and daughter of Lydon’s wife, Nora]. We had to look after her children, so it became very domesticated around here.

I loved Ari—really great energy.

You have to look out for your kids. That’s what families are for. FL