If films like The Village and Lady in the Water retroactively ruined—or at least diminished—M. Night Shyamalan’s good films, The Visit does the opposite for his bad ones. Shyamalan is so clearly in on the joke here that it’s almost plausible he might have been all along—like maybe The Happening was actually a brilliant piece of satire (Of course it’s not. But Shyamalan so clearly gets it this time that you kind of wonder).

What sets The Visit apart from The Sixth Sense is that it’s funny. What sets it apart from The Happening is that it’s intentionally funny. A horror movie by genre, The Visit plays like a comedy first and foremost, and it’s refreshing to see Shyamalan lean in to his campier tendencies—especially in a film whose premise is inherently campy.

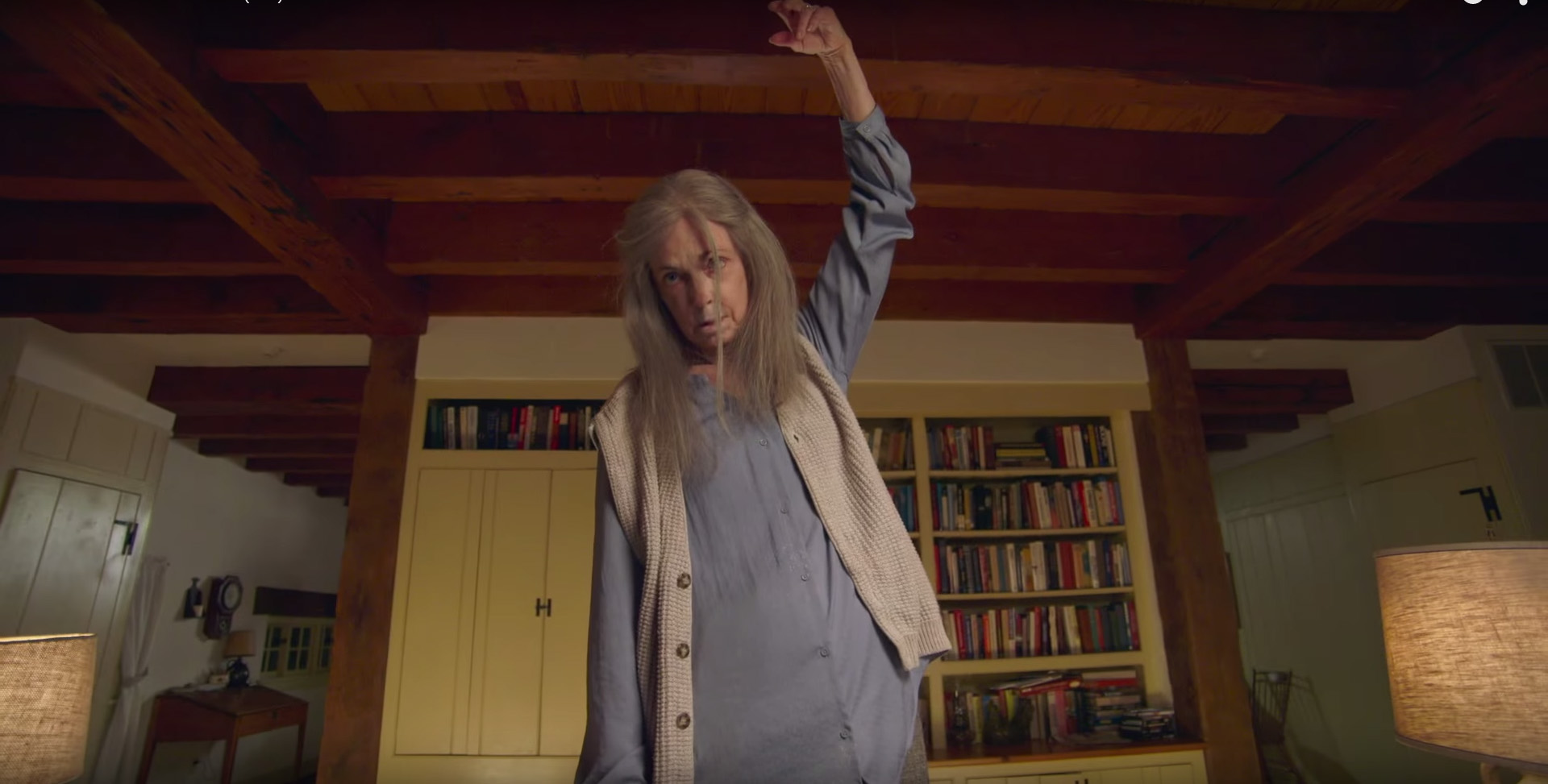

Becca and Tyler (Olivia DeJonge and Ed Oxenbould) spend a week with their grandparents (Deanna Dunagan and Peter McRobbie), whom they have never met, and things get weird. The poster’s “Don’t ever leave your room after 9:30 p.m.” admonition is because granny’s getting naked and clawing at the walls (among other things) after 9:30.

The premise hinges on the fact that old people can be kind of strange, and with a few notable exceptions toward the end, most of the scares are pretty standard weird old people shit, which conveniently solves the “But why wouldn’t they just leave?” dilemma that comes standard with most horror films.

The bulk of the credit for the success of The Visit, however, belongs to the stellar cast. Dunagan delivers camp with the best of them, but more importantly, she can act. The script has Nana rapidly switching from lucid to senile to just plain batshit crazy, and Dunagan doesn’t miss a beat. McRobbie is equally brilliant as Pop Pop, balancing James Cromwell likability with classic B-movie lunacy (Keep an eye out for the Yahtzee scene).

DeJonge and Oxenbould prove that directing children remains Shyamalan’s biggest strength, even if writing them isn’t—much of the kids’ dialogue is downright obnoxious. That DeJonge and Oxenbould manage to come across as convincing and likeable despite the clumsier aspects of what they’re given is a testament to their skill. Oxenbould’s character, Tyler, is an aspiring rapper and ladies man; it’s a bit of a tired trope, but he makes the trope feel, if not fresh, at least amusing enough to be worth the rehash.

DeJonge also breathes life into overly precocious amateur filmmaker Becca—an equally played out archetype, and the hook upon which the film’s found-footage conceit hangs—but what is most striking is how the two actors play against each other. That Becca and Tyler are convincing siblings makes all of the film’s less-believable aspects feel that much more realistic.

And for a Shyamalan film, The Visit is surprisingly well grounded in reality. For the first time since Unbreakable, Shyamalan plays The Visit’s reveal (it isn’t exactly a twist) perfectly, and he places it at the exact moment when the film is beginning to drag—all hell breaks loose just in time to feel like a payoff after the first two acts’ sparse scares.

Though far from perfect, The Visit is Shyamalan’s best film in over a decade, mostly because he finally stopped trying to replicate The Sixth Sense’s heaviness of tone. The result is an uproariously funny and—more importantly—fun film, and a truly triumphant comeback for Shyamalan. FL