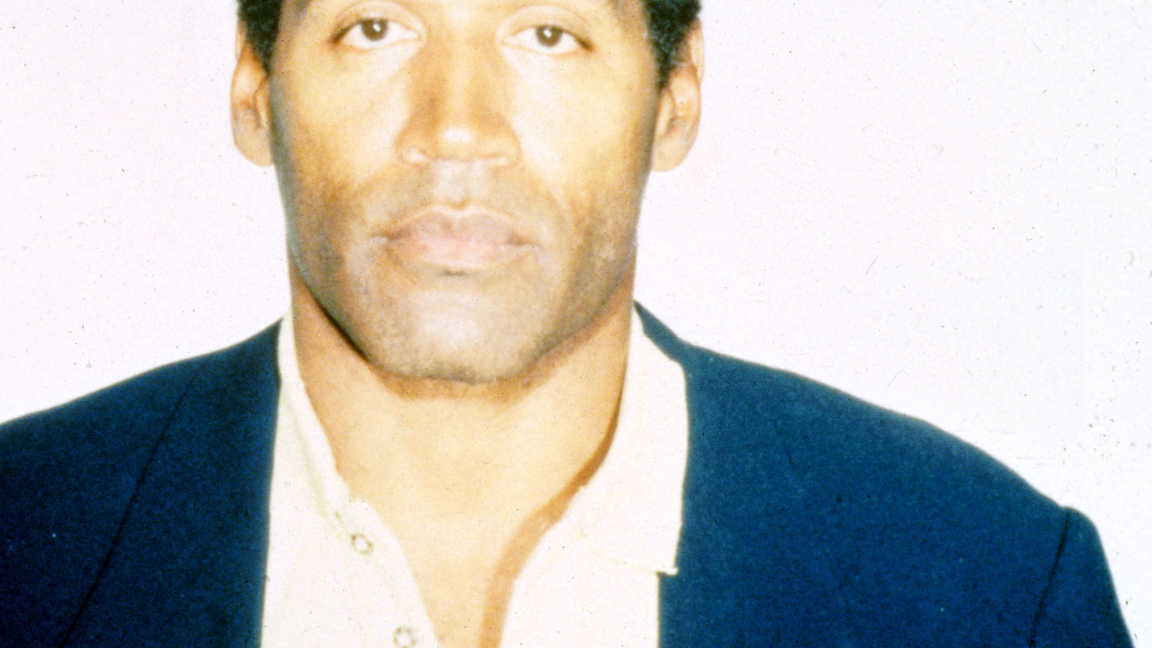

Last Friday, ESPN released the first trailer for O. J.: Made in America. It’s the sports network’s first attempt to expand their mostly successful 30 for 30 series of documentaries into a miniseries-length event, and on the outset it seems that there is no topic more deserving of the deep dive. While O. J. Simpson’s celebrity had certainly transcended football by the time he was arrested for the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman, that star was born on the gridiron. The case itself famously instigated or sustained ongoing conversations around race, celebrity culture, police brutality, and domestic abuse. When 30 for 30 has been at its best—see Jeff and Michael Zimbalist’s The Two Escobars or Jonathan Hock’s The Best That Never Was or Coodie and Chike’s Benji—it’s proven itself to be a series capable of both humanizing athletes and handling the complex socio-cultural conditions that surround and inform them when they take the field.

So it’s not the trailer for O. J.: Made in America that seems auspicious—it’s the timing. The Worldwide Leader waited for the dust to settle on FX’s American Crime Story: The People v. O. J. Simpson for all of two and a half days before introducing the world to their own take on the Simpson case. Ryan Murphy’s much-hyped (by us, at least) miniseries event portended to be a dramatic reconstruction not only of the case but of the racially tense world of LA post Rodney King. What we got, broadly speaking, was a show that fainted in the “right” directions—the very first episode opens with the King tape—before juking back toward middle-of-the-road drama with a slightly ironic bent: the question of whether Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden would kiss was invested with nearly as much emotional weight as the poor treatment of the jurors by the LA County system, and in the early episodes in particular, it couldn’t help but sneak in a few gratuitous digs at the expense of the Kardashian family, who were on the periphery of the case by virtue of Robert Kardashian’s friendship with O. J. (though David Schwimmer indignantly declaring that O. J. “will always be The Juice!” has to be one of the most quotable TV moments of the year). Given the prestige enjoyed by 30 for 30 in general, it’s not surprising that ESPN would strike so quickly.

And yet, something strange happened on the way to the verdict: The People v. O. J. Simpson began to take itself very seriously. The middle stretch of episodes found the series tackling race and the sexist pressures put on Marcia Clark, with directors John Singleton and Murphy developing Johnny Cochran and Clark as deeply complex characters being forced to act by the situation in which they found themselves. For Cochran, that was a world of consistent and brutal official discrimination against African-Americans at the hands of the LAPD, an issue that he rightly noted would be exacerbated by O. J.’s conviction regardless of the truth of whether or not he did it. For Clark, it was a life spent balancing the pressures of being a female prosecutor in a high-profile case—talk shows didn’t seem nearly as interested in, say, Cochran’s finery as they did Clark’s hair—with pursuing justice in which she firmly believed. As The People v. O. J. Simpson portrayed it, whether O. J. was guilty was almost immaterial to Cochran’s mission to create a media frenzy around a noble cause, whereas pursuing a guilty verdict was central to Clark’s mission, which was itself susceptible to the surrounding media frenzy whether caused by Cochran or not.

Whether O. J. was guilty was almost immaterial to Cochran’s mission to create a media frenzy around a noble cause, whereas pursuing a guilty verdict was central to Clark’s mission, which was itself susceptible to the surrounding media frenzy whether caused by Cochran or not.

This is the kind of interplay that 30 for 30 by its very nature as a documentary series can’t bring us. There may have been cameras virtually everywhere in the LA County courthouse, but there weren’t cameras in Cochran’s bedroom capturing his struggle to articulate his message through the media. There is no footage of Clark sitting at her desk in anguish as she confronts the reality of an admitted domestic abuser and, in her mind if not the jury’s, double murderer returning to the streets of LA to great jubilation. While The People v. O. J. Simpson was ultimately unsuccessful in re-immersing us in the discomfort of the mid-’90s, it nevertheless did succeed at localizing the case’s effects on its primary participants; even David Schwimmer’s waifish Robert Kardashian becomes a sympathetic character by the finale.

Where Murphy’s show failed, it seems reasonable to expect O. J.: Made in America to not only succeed, but to do what this series most needs to do following the media hype around The People v. O. J. Simpson: acquit itself. While the series can’t be as intimate as its FX counterpart, it can (and most certainly will, if the trailer is to be believed) mine the reserves of footage it has at its behest to paint an emotional portrait of society at large. From the moment he joined John McKay’s USC Trojans team in 1967, The Juice was a public entity. In addition to old game footage from USC and Simpson’s pro career, there are the abundant Hertz ads, the Naked Gun films, the many games he worked as a sportscaster, all of which the series will presumably play against his inevitable fall. There is the Rodney King footage, the Court TV footage, eight months of local and national news footage, eight months of talking heads reacting to the trial and to its effects in the outer world, and the idea of how all of this footage affected everyday life in Los Angeles and the United States.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nAyn1gDBc7s

The question of how what we see on TV informs the way we live is at the heart of the 30 for 30 series. Ken Rodgers’s The Four Falls of Buffalo traced the effects of the Bills’s four consecutive Super Bowl losses on the city of Buffalo itself in a tight, nuanced way that honored its chosen subject. This is the challenge that director Ezra Edelman has before him: to synthesize and recast all of that footage into a coherent, illuminating, and affecting story about how the Simpson case changed the lives of not only its principals but of the millions of people who witnessed it every day, and how those millions of reactions reshaped our society.

It’s a tall order. And if it makes Murphy’s project seem tame in comparison, it shouldn’t. We need both of these series. The O. J. trial and all that surrounded it did not define what it means to live in the United States at the turn of the century. But those events are nevertheless emblematic of American life today, in which the personal and the political are more intertwined than ever before. It is, perhaps more than anything else, a deeply American tragedy. FL