“Who knew we were being historic? We just wanted to do comix!” Trina Robbins, one of the founders of Wimmen’s Comix, exclaims. Launched in San Francisco in 1972 amid the “underground comix” boom, Wimmen’s was a proudly feminist, stridently political publication created solely by female comic creators.

The entire run of the series—including its predecessor, the single issue It Ain’t Me, Babe—is being collected this month by Fantagraphics Books as The Complete Wimmen’s Comix. Housed in a gorgeous slipcase, the collection features over 700 pages of comix, covering topics like the occult, sex, history, relationships, homosexuality, body image, and more. Over the span of seventeen issues, the series featured the work of cartoonists like Phoebe Gloeckner, Lynda Barry, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Patricia Moodian, Diane Noomin, and Alison Bechdel, progenitor of the Bechdel Test. Their comix are in turn hilarious, psychedelic, spooky, and wonderfully weird, as revolutionary and strange as the best-known underground comix by male peers Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, and Spain Rodriguez.

Robbins has written about and created comix since the late ’60s, working for small publishers as well as Marvel and DC Comix. She discussed the origins of Wimmen’s Comix, its influence, and its impact with FLOOD from her place in San Francisco.

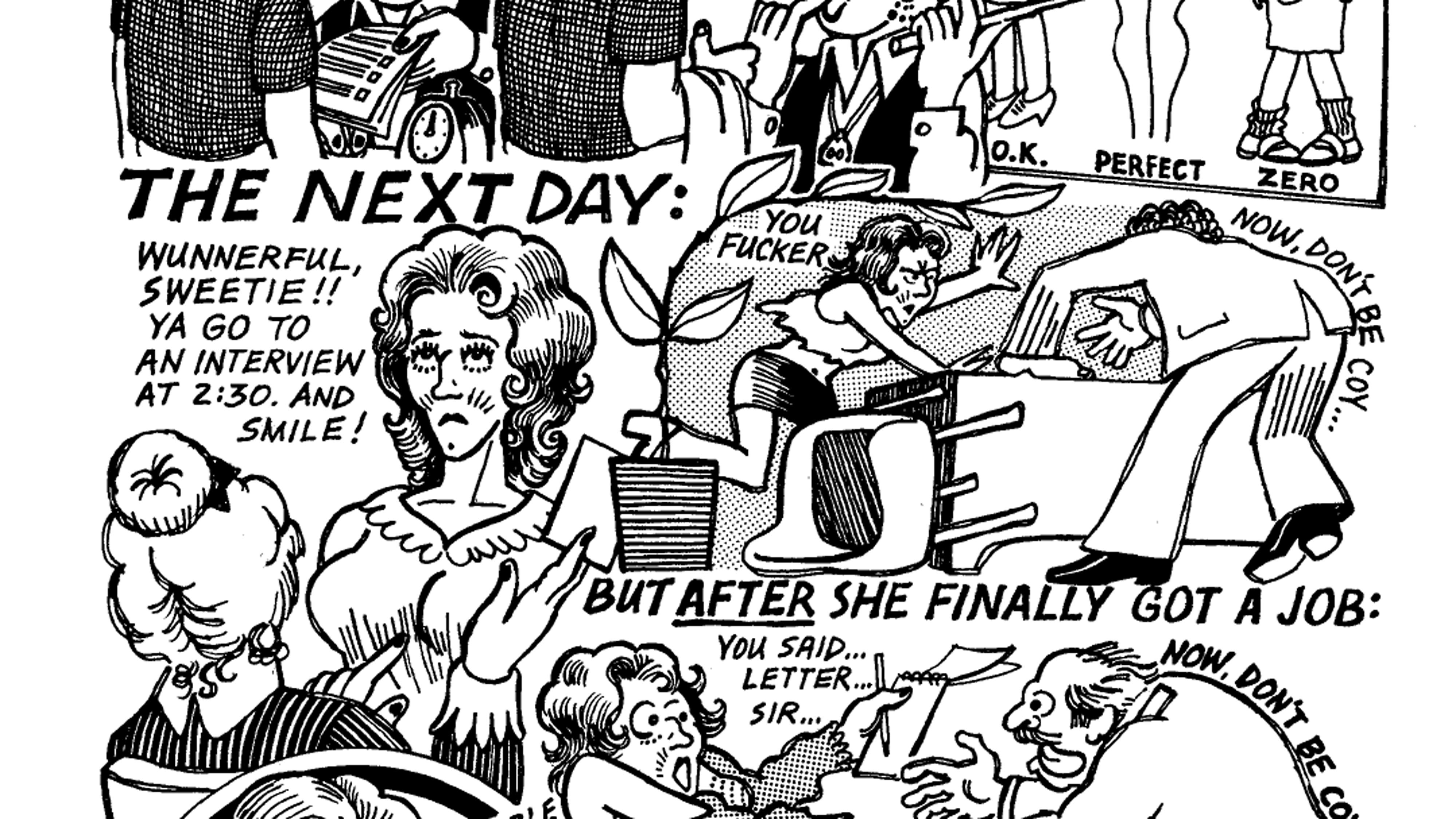

“Dr. Sigmund” Lynda Barry’s “Seven Deep Psychological Problems”

I wonder if you can give me a sense of how the scene felt in the late ’60s. Did the counterculture—music, comix—all feel like the same “thing” at the time?

Yes, they were connected. For one thing, I think all the rock-and-rollers read comix. It was a new thing. Up until then it had just been superheroes, and suddenly there were “comix” and they were about us. They were about our generation and our way of life.

It Ain’t Me, Babe, which was spun out of a feminist newspaper of the same name, featured Wonder Woman, Olive Oyl, Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, Little Lulu, and Mary Marvel on the cover.

And Elsie, the Borden Cow.

Oh right! You were a fan of comix even before the counterculture movement. Was that cover a nod to your own comic fandom?

Oh yes. But it was just a statement. It was: look, all these female comic book characters—I can’t say women because Elsie’s not a woman—but all these comic book females are rebelling. That was the statement.

What was the atmosphere like in San Francisco in those days?

[The art coming out] was relating to us and our lifestyle. Although of course, the women’s liberation movement had started and for a reason. It started because the counterculture was very male dominated and rather misogynist.

“There were really two women in San Francisco drawing comix: me and Willie Mendes, and that was it. They didn’t invite us into their books.”

I’m drawn to a lot of counterculture art of the era and appreciative of it, but I imagine it must have felt for you women that you were getting the same sort of crap from these guys as you would have from “square” guys, that they just had longer hair and better rock songs. Is that how it felt?

[Laughs.] Yes! In many ways, [they were] more openly misogynistic. I don’t know how to describe it. All those rock and roll songs of the period [were like,] “Babe, we just had some good times but now I gotta go rambling on.” That was it. There was no commitment at all, whereas with the old fashioned thing of the ’50s, there was at least a kind of a bargain there—though it was not a good bargain. But the bargain was: if you can stay a virgin, he’ll marry you and he’ll support you and you’ll take care of the house and raise the babies. Which is another kind of misogyny, but actually it was a bargain, whereas there were no bargains at all in the counterculture relationships.

What was the reaction like from the mostly male underground scene when you first started publishing Wimmen’s Comix?

Well, it was all male. In San Francisco, the seat of the underground comix movement, it was all men. There were really two women in San Francisco drawing comix: me and Willie Mendes, and that was it. They didn’t invite us into their books, which is another reason why we had to do our own.

How did you go about connecting with other women across the country? This is obviously before e-mail.

Before the Internet, yes it sure was. As soon as the first book came out, It Ain’t Me, Babe, women started contacting me. The comic went all over the country, and women saw it and thought, “Wow, a comic by women, how cool!” The first issue of Wimmen’s Comix asked for contributions and we got them. We got mail and art all the time. We would have meetings about once a month and go through everything sent to us. It was very exciting.

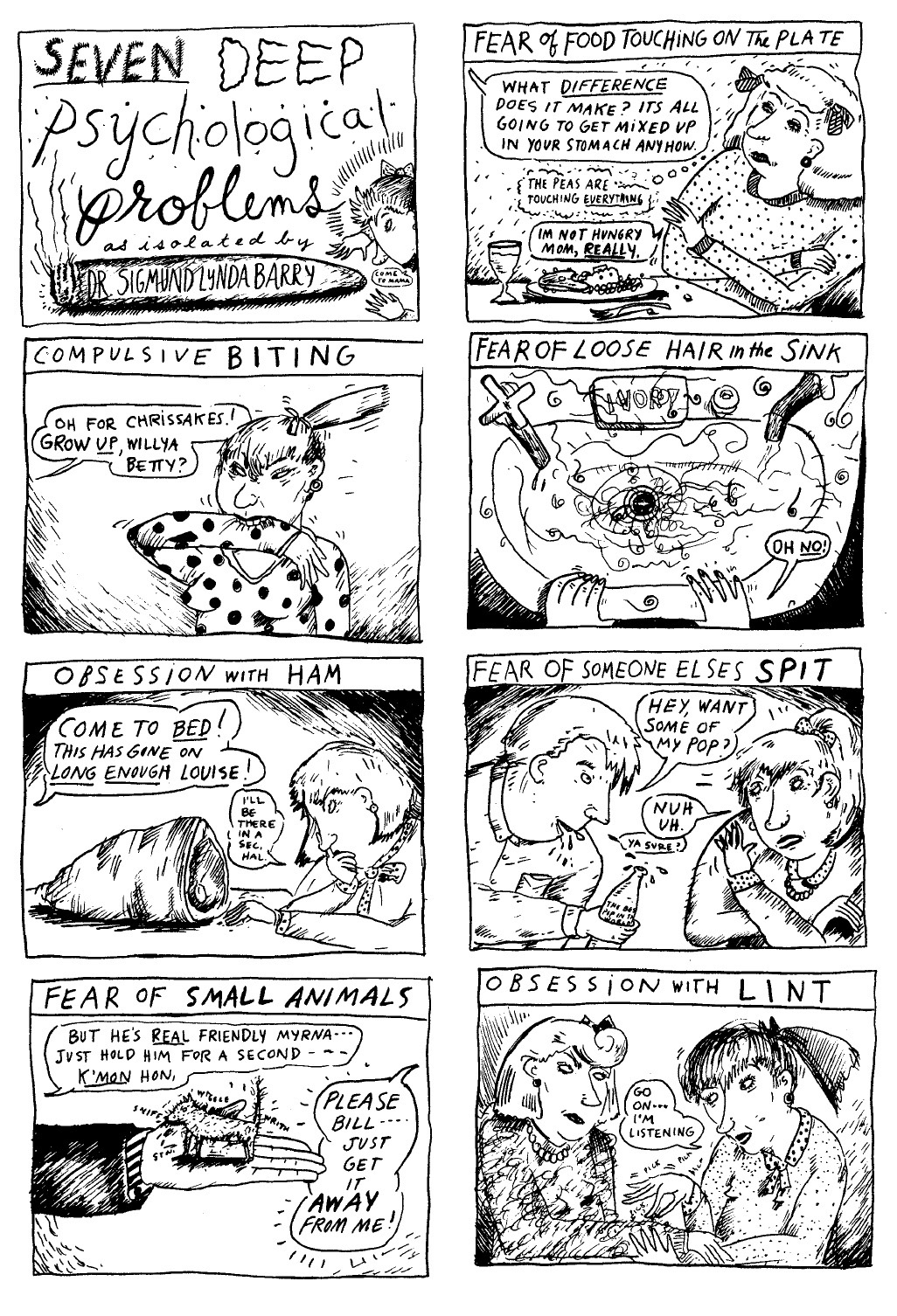

Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s “Goldie Gets By”

A lot of the stories convey sex, but they do so in a way that’s so different from what you see in a lot of the more masculine comix of the time.

I’ll say. [Laughs.]

Were there discussions in the meetings about the content you wanted to feature or did you leave it up to each individual creator?

It was up to the creators, of course, but because it was underground, there was no Comix Code Authority seal of approval; we could deal with these subjects: sex, lesbianism, abortion, periods. Of course the guys never wrote about that stuff.

What kind of reaction did you have from other feminists? I’m sure not everyone loved everything.

[In the collection we’ve printed] this wonderful piece of hate mail [from a feminist critic condemning the publication]. It’s hilarious. I’m so glad I saved it. Obviously, yeah, there were feminists who thought we were dreadful. But at the same time, there were feminists who loved us. We were carried in women’s book stores.

And head shops alike. Was there crossover across genders?

Oh sure! Guys read our books, absolutely.

“Obviously, yeah, there were feminists who thought we were dreadful.”

In 1976, two Wimmen’s contributors, Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Diane Noomin, started another title, Twisted Sisters. Even if there were some creative differences, it must have been exciting to know that the idea of women in comix was expanding and wasn’t being relegated to just one publication.

By then [there were other publications by women]. Not just by then—even two weeks before [the first issue of It Ain’t Me, Babe] we were beaten to the stands by [the all-female anthology] Tits & Clits Comix, which was coming out of Southern California. From the very beginning there was more than Wimmen’s Comix. It was like a tennis game, batting things back and forth. It’s always fascinating that on either side of one state, two different books of all feminist comic books came out within two weeks of each other. How did that happen? We didn’t even know about each other. But eventually New York got into the act, too.

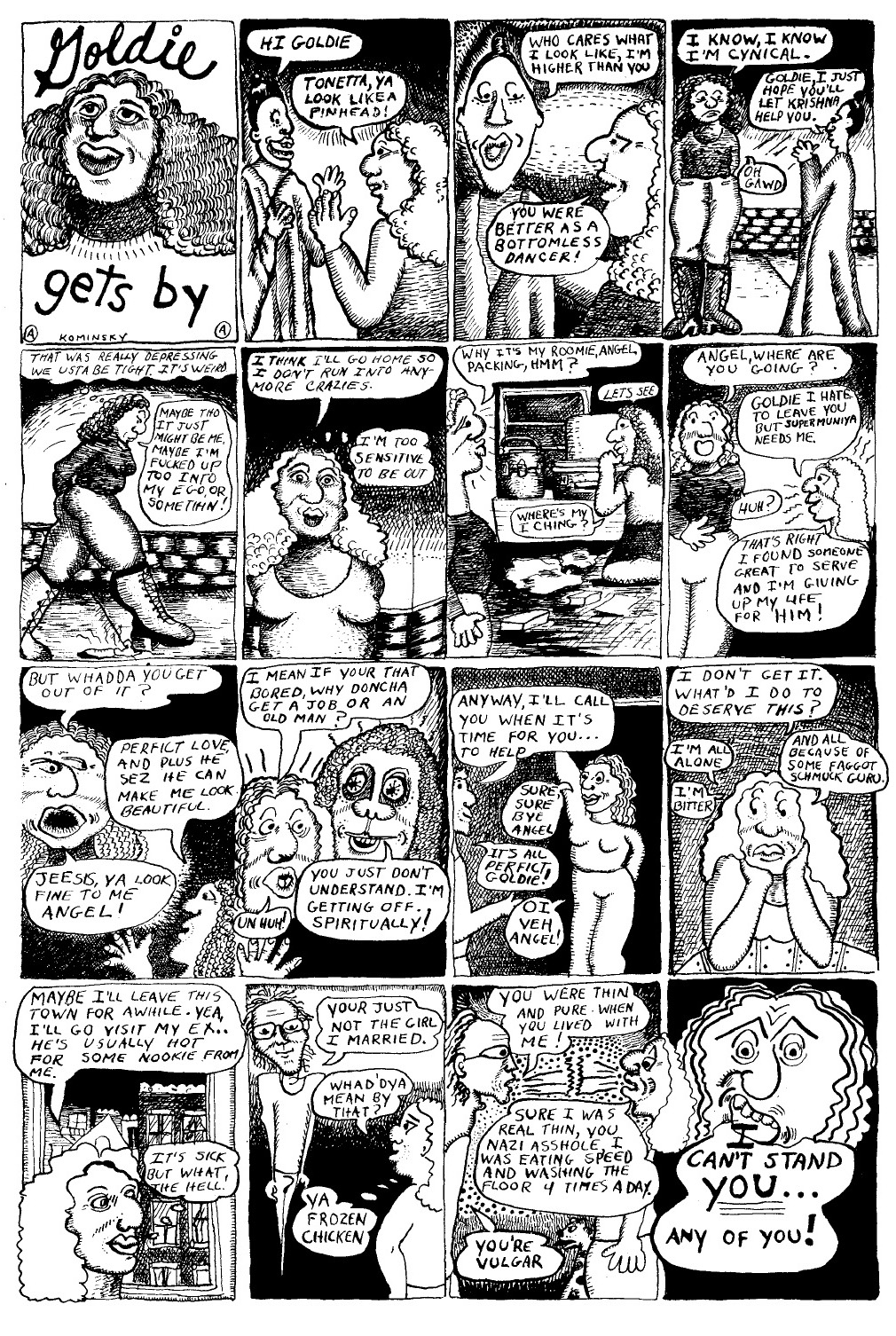

Alison Bechdel’s “Dykes to Watch Out For”

As distribution moved from head shops into traditional comic book stores, Wimmen’s faced some challenges.

That’s putting it mildly. We did lousy in the comic book stores. Direct sales killed us really in the end. All they wanted to carry was superheroes aimed at boys and young men. They didn’t carry us, or else they carried a tiny amount—like two copies—and when they sold out they didn’t reorder.

You’ve written extensively about the history of comix and continued as a creator. Do you still think that comix at large feels like a boys’ club in 2016?

Not at all. What has changed things is graphic novels. Book stores and libraries carry graphic novels. You don’t have to be dependent on the dreaded comic book store anymore—and even comic book stores, so many of them have wised up and are much more girl-friendly places than they used to be. There are so many more women drawing comix—you see so many women drawing graphic novels and [creating comix] on the Internet.

There are historical stories about women of color in Wimmen’s, but did any women of color contribute to the series?

I’m afraid most of the creators were white. The only person of color [who contributed] was Edna Jundis, who is Filipino. Believe me, we didn’t do this on purpose. It was a question of who sent us work. We never received work from women of color. Every issue we asked for contributions, we were very open to it… We were also, in the beginning, in some feminist publications, called heterosexist, because there were no lesbian cartoonists. But that was simply because no lesbians had sent us comix. Then, in 1974, we got this great comic from Roberta Gregory, which we published. We didn’t publish it because “Uh oh, we better publish it because it’s by a lesbian,” it was, “Hey, let’s publish this because it’s really good.”

It’s often stated that there aren’t very many women in comix, but this collection shows that there have been plenty of women making comix for a long time.

And not as many people think that anymore. Women in comix are everywhere. Sometimes I think there are more women drawing graphics novels than men. If you really still think there aren’t many women in comix you need to wake up, drink some coffee, and look around you. FL