A burst of pure pop-art psychedelia, The Beatles’ 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine is a gloriously weird combination of Fab Four jams and counterculture-inspired cartooning. The film’s influence on comics painter Alex Ross might not be immediately apparent, but it blew his young mind. “I absolutely adored it,” the artist says. Coming up in the early ’90s, Ross pioneered a singular style, merging Silver Age exuberance with photorealism. In his breakthrough 1994 miniseries Marvels, Ross made his love of the Beatles clear, creatively sneaking them (along with his other favorites, including Badfinger, The Who, and The Monkees) into scenes.

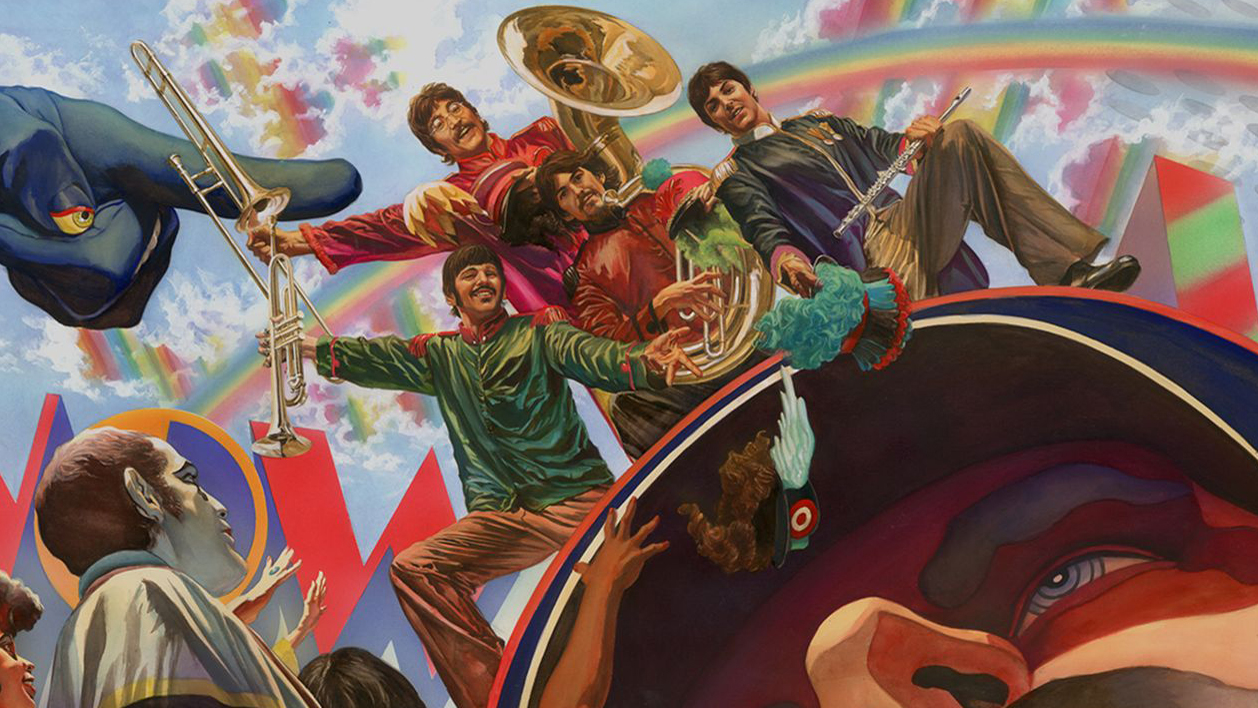

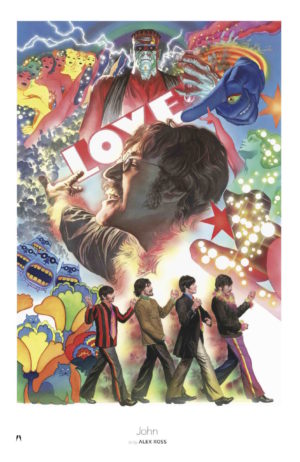

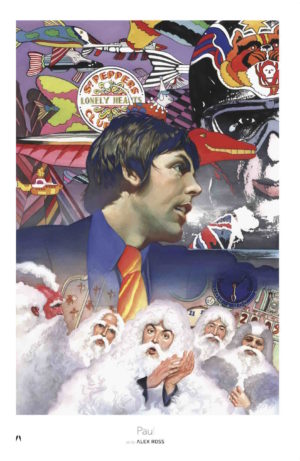

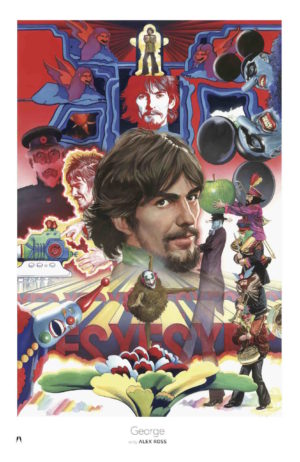

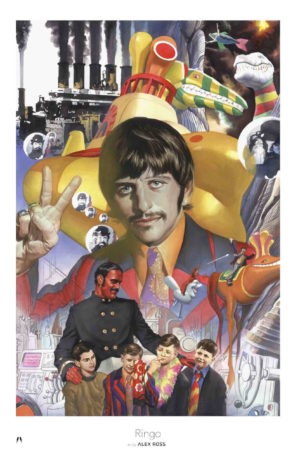

On April 30, Beatles fans will get to see Ross’s fandom in full effect when his specially designed Yellow Submarine box set is revealed at The Beatles Shop at the Mirage Hotel in Las Vegas. The project is a high profile one, even for a guy known as one of the most famous artists in comics, whose work has appeared on TV Guide covers and on the silver screen in Spider-Man and Spider-Man 2, and whose continued dominance of the Comic Buyer’s Guide Fan Award for favorite painter led to the publication retiring the category. Fusing his trademark style with the wild animation of the movie, Ross imagines an alternate reality in which Yellow Submarine was shot Who Framed Roger Rabbit–style, blending animation and reality.

FLOOD spoke with Ross about The Beatles, the twentieth anniversary of his genre-defining Kingdom Come, and his thoughts on Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice and the upcoming Captain America: Civil War. (Spoiler alert: Ross discusses the events of the former film and speculates as to the events of the latter.)

Do you remember seeing Yellow Submarine for the first time?

Do you remember seeing Yellow Submarine for the first time?

Yeah, I think I was [around] six years old when I saw it on TV, which would have put it in the mid-’70s. It’s so utterly surreal. I don’t think there’s anything you can compare it to, given that the art style is so unlike a Hanna-Barbera cartoon… It doesn’t necessarily humanize or make [The Beatles] intimate to you; they’re very mysterious caricatures. Their features and the Peter Max–like art style is so utterly bizarre, but I absolutely adored it. It’s remained one of my favorite films of all time.

Your work is rooted in reality. Certainly these prints capture the likeness of The Beatles in a way that the film doesn’t ever aspire to, but they don’t shy away from the far-out aspects of the film either. Was it a challenge to integrate that psychedelia into your work?

I didn’t really compromise my general approach, which is “I’m going to make them realistic.” Some of the other side characters show up looking like realistic people, too, as if they’re portrayed by actors instead of cartoons. I treated it as kind of a Mary Poppins–like film, entertaining the possibility that if they had starred in this film in 1968 and were acting against green screens, you would have had this animation integrated with them. Certain things I decided not to translate into looking more realistic—like the four-headed bulldog, [which I] left flat [and] looking more like a cartoon—because I want the integration. There’s such a beauty to that design work. I’m imagining background sets looking physically flat in some respects, [but] with other characters, I do want to see an actor like Victor Spinetti, who was in all the Beatles films, imagining someone like him playing the Blue Meanie in makeup and an outfit.

There are people who’ve spent a lot of time examining some of the allegorical possibilities of Yellow Submarine—that the characters represent aspects of the Second  World War, or that the film is laden with occult symbolism. Have you read some of the strange fan theories regarding the film?

World War, or that the film is laden with occult symbolism. Have you read some of the strange fan theories regarding the film?

[I’m surprised fans assume] The Beatles themselves controlled the movie so much that they were adding in these mysterious symbols. But I’m intrigued! Of course, when you look at stuff like the sequence with George and the fantastic realm he first comes from, you would be wondering, “Wait a minute, what are the cows for?” There are these griffins—which I illustrated in his portrait—[that are] just surreal and fun looking. I don’t grant that much more depth to it.

That’s probably a fair way to approach it. The Beatles themselves ultimately signed off

on the film.

But they were very removed from the project. [Still,] it feels like a pure Beatles movie — a Beatles “communication effort”—as much as any single album or as much as even Hard Day’s Night, the ultimate, perfect Beatles movie.

I think there’s just a lot of room left for the viewer to infer meaning. There’s a lot of power in suggestion.

It’s a visual and cultural melting pot… Anything that could be grabbed from pop culture and history can be thrown in.

As a kid, you were introduced to Spider-Man via The Electric Company. You haven’t shied away from bright, colorful renditions of superheroes. There’s a Silver Age, ’60s and ’70s brightness to your stuff. I don’t want to dwell on the idea of darkness in films like say, Batman v. Superman—

[Laughs.] I was fearing this is where you were going.

What do you think of that? Your portrayal of Superman so captures what I love about the character—there’s a shining quality to him, a gentle, heroic feel. What do you think about a film like Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice?

[Laughs.] I have to choose my words wisely. Sometimes situations with movies like this are fraught, because it seems like you’re, you know, raining on someone else’s parade, but I think [you don’t want to] lose sight of the charm that needs to coexist with these characters, no matter how dark or realistic  you want to make the material and appearance. Obviously, with a movie like Deadpool, there’s loads of charm to it. It’s still got all the dark, aggressive stuff that you’d expect the character to have, but if there ain’t no charm, you’re missing the whole point.

you want to make the material and appearance. Obviously, with a movie like Deadpool, there’s loads of charm to it. It’s still got all the dark, aggressive stuff that you’d expect the character to have, but if there ain’t no charm, you’re missing the whole point.

It’s not purely about how brightly colored they are, but you need to like these people, these characters. If you miss that boat, if you don’t translate that on screen like we know was done thirty-five years ago with Christopher Reeve, you’ve wasted the character’s time and made a false impression in the minds of people about just how charming these concepts should be. The pure concept of a character who’s altruistic should be a powerful and inspiring narrative. The entire thing of building up to a character who’s decided to take their particular assets in life—whether it’s their riches or their strengths—and apply it to helping others: [that’s a] powerful and compelling narrative. If you don’t know how to tell that story, you shouldn’t be working with it.

Your most famous work, Kingdom Come, celebrates its twentieth anniversary this year. Did you envision what you were doing there to be a comment on the nature of the ’90s comics that were its contemporaries?

Oh, it was, absolutely. I intended it to be a bookend with Marvels, [which] was a light repudiation of the explosion of so many new characters and so much of the rethinking and redesigning of characters [there was] in the ’90s. We showed classic, more simplified versions of them from the ’60s, [tapping into] this wonderful energy and putting it in competition with what was happening at the time. Then, jumping ahead [with Kingdom Come] to a comic book apocalypse of sorts, where you have too many characters almost eating each other up… In the practical world, what it meant was that [the creation of] too many characters was leading to the destruction of the publishing world. The explosion was going to contract and ultimately collapse in on itself. There was too much going  on, too much of a strain on the fanbase. Kingdom Come was, in its part, a very heavy-handed metaphor for that idea. It didn’t come about except [as a response] to the times it was in.

on, too much of a strain on the fanbase. Kingdom Come was, in its part, a very heavy-handed metaphor for that idea. It didn’t come about except [as a response] to the times it was in.

Was it also a comment on the way heroes were being portrayed at the time—dark and grim?

In general. Not so much picking on one characterization, because it was key for [writer] Mark Waid and myself that we never poorly represent characters that we love. The heart of the story [is about] DC archetypes: Captain Marvel, Wonder Woman, Superman, and Batman. It’s about those primary icons of comic book history dealing with the changing times and the collapse of the superhero.

It’s done in a way that ultimately underscores these characters as aspirational in nature. They can serve as reminders of our best selves. Kingdom Come celebrates that, and that’s one of the reasons it’s endured as a story for twenty years. Stories that point to how good people can be might not always be fashionable, but they are appreciated.

I don’t think they’re terribly fashionable at the moment. [Laughs.] But that will change. Even in the movie world, we’re gonna have [Marvel’s] movie of virtually the exact same plotline [as Batman v. Superman] happening.

You know, I think those Captain America films share elements of the Christopher Reeves Superman films.

Absolutely. God help us if they kill off Captain America—as I fear they might. The pain will be that much more, as we’ve got to know him over the course of these movies. But I imagine they’ll communicate that in a way that’s poignant. I don’t want them to! I wish they wouldn’t. But in their movie universe, we know it’s not the end, just like we know it’s not the end in the DC movie universe. Those are great filmmakers [Anthony and Joe Russo, directors of Captain America: Civil War], so I expect great things. FL