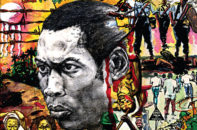

When Lemi Ghariokwu met Fela Kuti, the pioneering Nigerian musician and bandleader who is to his continent what James Brown is to this one, Fela said two words to him: “Wow, goddammit!”

Lemi had drawn a portrait of the Afrobeat star at the behest of journalist Babatunde Harrison. Harrison had seen Lemi’s self-commissioned poster for Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon hanging in a Lagos bar and immediately asked the artist if he could do album covers. “I didn’t believe him,” Lemi says of the journalist’s insistence that he and Fela had been discussing the need for a new artist only days prior. “Fela was already huge thanks to his controversial lifestyle,” he explains from his home in Lagos via Skype. “He was popular in a notorious way. Like Snoop Dogg.”

That initial meeting in 1973 changed Lemi’s life. From there, he’d become one of Fela’s closest confidants despite being seventeen years his junior, and, as he puts it, the two were “comrades in arms.” They studied metaphysics together, they read Marcus Garvey and Malcom X, they discussed Pan-Africanism. “I became like his son,” Lemi says. “When he was recording a tune, I was close to the process, so by the time he recorded the album, it was almost a fait accompli for me to illustrate the album. Most of the time, ninety percent of the time, he’d say, ‘Lemi, it’s a motherfucker, man.’”

With grooves deeper than a World War I trench and horn charts sharper than a bamboo fence, Fela’s music is still, nearly twenty years after his death, almost absurdly vital. It is a sound that seems to have its own shape, its own body. It’s also highly political music whose consequences seem hard, if not impossible, to fathom from a North American perspective; most famously, Fela’s Lagos compound was once held siege by the Nigerian military, who threw his seventy-eight-year-old mother out of a window, injuring her fatally. His album art needed to be as conscious as his music. “I love to say that in the beginning it was the music, and the music was so powerful that it needed accompaniment,” Lemi says. “My art played that role. My art had to act as a megaphone for voicing Fela’s ideas.”

“I was conscious of when the Black Panther movement was very strong in the United States, and of when George Jackson was killed in San Quentin Prison. I cried, and I felt like, ‘Wow, black people are suffering,’ do you understand?”

It was a role he’d been prepared for long before he picked up a pen. “From when I was eleven years old, I was conscious of my race and my African-ness. I knew when Miriam Makeba left South Africa for exile in the US—I still have the album of she and Harry Belafonte from 1965,” Lemi says. “I was conscious of when the Black Panther movement was very strong in the United States, and of when George Jackson was killed in San Quentin Prison. I read about him in Drum magazine. I did a portrait of his. And I cried, and I felt like, ‘Wow, black people are suffering,’ do you understand?”

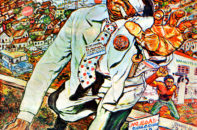

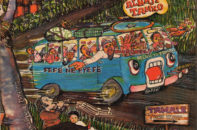

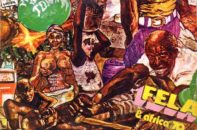

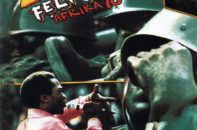

Lemi’s Fela covers are vibrant, nuclear-blast-bright illustrations that depict suffering with such wild anguish it would make Hieronymous Bosch blush. 1982’s Original Suffer Head, which was recorded shortly after another violent raid on Fela’s home, shows Africa as a warrior bleeding oil and forced to carry water it’s not allowed to drink. A long line of people forms below the continent and winds its way to a suspiciouslooking voting box in the foreground. Behind them, a jet flies over a football stadium. Like the album it covers, Original Suffer Head is at once intricate in its attention to detail and blunt in its frank execution and accusatory posture toward the Nigerian government. On the cover of 1976’s No Bread, a man in a mask is literally carrying a bucket of shit while behind him another man blows up a balloon stamped with the phrase “Mr. Inflation is in town.” A bare-breasted woman stands between them, offering up her body.

After he and Fela parted ways, Lemi went on to create over two-thousand album covers for other acts, working for just about every single record label to open an office in Nigeria. While his output has been prodigious, those covers were “not in the same style as Fela’s,” he says. “Most of them are mundane.” He also supplemented his early income with advertising gigs, executing letterhead and brochures for local agencies.

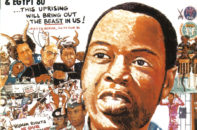

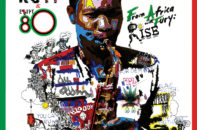

Which isn’t to say that his post-Fela output has been insignificant; a 2002 illustration entitled Anoda Sistem is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, and he continues to show his own fine art pieces around Lagos. He also recently worked with Fela’s son Seun, who took over the reins of his father’s band Egypt 80 following the senior Kuti’s AIDS-related death in 1997.

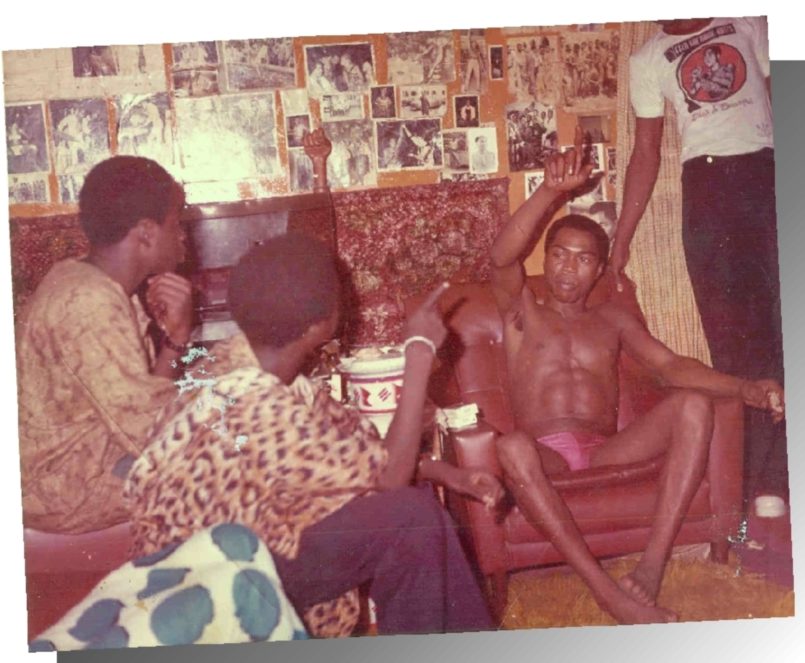

Lemi Ghariokwu (far left) with Fela Kuti (right)

Still, it’s the work Lemi did with Fela that endures, and talking to him, you get the sense that he wouldn’t have it any other way; the gratitude he feels toward his late comrade is apparent in the notes of pride that appear in his voice when he talks about their relationship. “Fela didn’t respect anyone [initially], but when you had something to offer, he showed so much respect,” he says. “[He] gave me so much freedom of expression.”

That freedom resulted in a body of work that is still influencing artists halfway around the world. When Lemi made the trip to New York for the opening of the New Museum’s 2003 exhibit Black President: The Art and Legacy of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, he was the only one of the thirty-four featured artists to have actually met the man himself. “We got to know Fela through your art,” he says the other artists told him. “We’d go into the record store and [look at the cover and] say, ‘Oh! What music is in this?’ You are a legend.”

Still only sixty, Lemi is now organizing his archives and preparing to open a museum of his work in Lagos, where people continue to come to pay respect to what he and Fela created. It’s a motherfucker, man. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 3. You can download or purchase the magazine here.