In their original incarnation in the late ’70s and early ’80s, The Feelies were known for playing nearly exclusively on national holidays. A show of theirs was always a celebration of some kind—like firecrackers going off in a cul-de-sac on the Fourth of July. Though they wouldn’t necessarily have known it at the time, anyone lucky enough to have seen the band back then should have indeed been celebrating the occasion: of all the obscure artists among the heavily dog-eared pages of rock and roll lore, perhaps none have been as unpredictable as The Boys (and Girls) with the Perpetual Nervousness led by Glenn Mercer and Bill Million.

This summer marks forty years since The Feelies first formed in a suburban New Jersey garage, molded by a chance encounter and a mutual love for The Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog”—except that nice round number doesn’t really tell the whole story. At least twenty of those forty years are accounted for by two extended band hiatuses (the first lasting from about 1980 to 1985, and the second from 1991 all the way to 2008, when they were asked by Sonic Youth to reunite), and all said, there have been two lineup changes, three side projects, and four record labels surrounding five total albums—each one essential to the legacy of a band that never seemed to be all that concerned with something as silly as “legacy.”

The “Crazy Rhythms” Lineup: Anton Fier, Bill Million, Glenn Mercer, Keith DeNunzio

From the frantic landmark debut Crazy Rhythms, the sun-glazed minimalist masterpiece The Good Earth, the massively underappreciated major-label turn Only Life, the hard-nosed ragged glory of Time for a Witness, and the shockingly assured return of Here Before, The Feelies have spun together a catalog that surely belongs in conversation with The Velvet Underground, Talking Heads, and R.E.M. The catch? Generally speaking, you have to want to be in that conversation in order to be regularly invited into it.

“We’re really appreciative of our fan base and happy that they like what we do, but really, we do it for ourselves,” says Mercer, who has to qualify as one of the most soft-spoken lead singers ever. “We don’t rush into anything.”

It should be reassuring, then, for the band’s very patient fans to hear that the currently reunited classic lineup—with Mercer and Million each on guitar and vocals, Brenda Sauter on bass, Dave Weckerman on percussion, and Stanley Demeski on drums—have a new album on the way. Like every other Feelies record, it’ll be completely different from every other Feelies record (for starters, this one is said to be largely home recorded).

The Classic Lineup: Brenda Sauter, Glenn Mercer, Dave Weckerman, Stanley Demeski, Bill Million (photo by John Baumgartner)

“I don’t think we go into a recording situation with this feeling that we’re one hundred percent intent on making a certain type of record,” says Million, who is also soft spoken, but a regular chatterbox compared to Mercer. “We have an idea but a lot of times these things take a life of their own, and that’s one of the things that we really love about making music.”

In celebration of Bar/None’s recent reissues of the band’s A&M releases (Only Life and Time for a Witness), and in anticipation of album number six, Mercer and Million reflect here on forty years of feeling it out with The Feelies, album by album.

Crazy Rhythms (1980)

Glenn Mercer: By the time we were recording Crazy Rhythms, there was this punk rock thing happening in New York and we definitely felt some solidarity. But we didn’t want to align ourselves too closely because we kind of felt like, “Well, this has been done before, it’s been done better.” And they were kind of [going off on] the fashion aspect with the safety pins… So I think we just kind of steered away from anything that resembled what was going on in New York. We wanted to stand out. We wanted to carve out a sound that was unique.

Bill Million: We’d made the decision that when we did record an album, we were going to be in charge of the sound. So we went in with that determination; however, we were still pretty much novices. We started turning dials and discovering sounds, and after about eight hours of struggling to get a guitar sound, we said, “Let’s try something different.”

Mercer: Mark [Abel], our co-producer, said, “We’re scheduled to mix in a week, we have to move on. Why don’t we just record the guitars direct and then when we go to mix we’ll feed ’em back to an amp—I’m sure it’ll sound better there.” But we kind of got used to the way the guitars sounded direct, so we ended up keeping ’em.

Million: A lot of times the environment takes over—some unknown element takes over—and you have to be smart enough to be aware of what’s happening and try to enhance it. And I think that’s what we did.

The Good Earth (1986)

Million: We turned down a lot of major labels because they wanted to bring in a producer to work with us. One of ’em was Philip Glass, and Glenn and I went to meet him. After a while he looked at us and said, “Well, you guys sound like you know exactly what you want, you don’t need me.” So it was cool meeting Philip Glass… [Laughs.]

Mercer: I think we just felt a certain comfort level working with [Peter Buck of R.E.M., co-producer of The Good Earth]. We knew that, being a guitar player, he’d certainly be sympathetic to the way we approached the songs and the mixing and the arranging. We knew he wouldn’t be heavy handed, come in with a whole bunch of [pre-conceived] ideas. He was perfect for the job.

Million: With The Good Earth and [legendary Hoboken venue] Maxwell’s and Coyote [Records], it kind of grew out of a friendship with Steve Fallon, who owned Maxwell’s, and the whole vibe of the club, which we absolutely loved. It was the complete opposite of what we had experienced in New York. It was more low-key and we found it more genuine and much more suitable for the band.

Mercer: It just seemed like a good time. Bands like R.E.M. were inspiring this whole new wave of American bands. The same way we had been influenced and inspired by what was going on in New York, I think [the same was happening in] California—Dream Syndicate, Rain Parade, Green on Red. So it just seemed like a really good time for independent music—alternative whatever-they-call-it: college rock.

Only Life (1988)

Mercer: Overall, bands that we considered our peers were signed to major labels. It kind of seemed like that situation where you gotta keep moving up, and [there were] a lot of high hopes both on the side of [A&M Records] and the band, I think, for something to happen.

Million: For us, everything always kind of starts with the songs in front of us—and how we want to record them. When [Only Life] was complete we were perfectly happy. We did go on tour but I think that also was a time where we [decided], “Let’s give this a chance and see if this is something that we want to do as a career.” And as it turned out in the long run, it was the wrong decision. It was something that just didn’t fit us. But we gave it a chance.

Mercer: I remember Bill and I did an interview with somebody from England where we said, “Well, we don’t mind being a cult band, all our favorite bands are cult bands…” And this guy got really mad! “You’re full of shit, nobody’s like that, everybody wants to be as popular as they can be…” We’re just not comfortable with certain aspects of the music business. We’re just kind of shy, really. We’re not the kind of band that gets up and is like, “Hey, everybody!” [Laughs.]

Time for a Witness (1991)

Million: I think by the time we got to Time for a Witness, we realized that the very base of the song has to have a groove. I think that you can hear. It also reflected a lot of what was going on. At that time it was more of an overdriven type of sound like we first heard with Neil [Young]. So we set up on a stage and that’s how we recorded it—much more similar to what we would do as a live band. And I think that kind of loaned itself to that album.

Mercer: A&M got bought out by PolyGram and a lot of people we knew at the label left—or had been fired, I dunno. New people came in, they weren’t familiar with the band, they didn’t really seem to care much. There was personal stuff going on as well.

Million: Glenn and I had said this right from the very beginning: if it ever came down to someone not having fun doing it then [they] probably should stop. And that’s exactly what happened to me. I’d be looking down at my set list during a show, thinking, “I just have three more songs left to do.” So one thing led to another and I decided that I needed to take a break. The break just lasted seventeen years. [Laughs.]

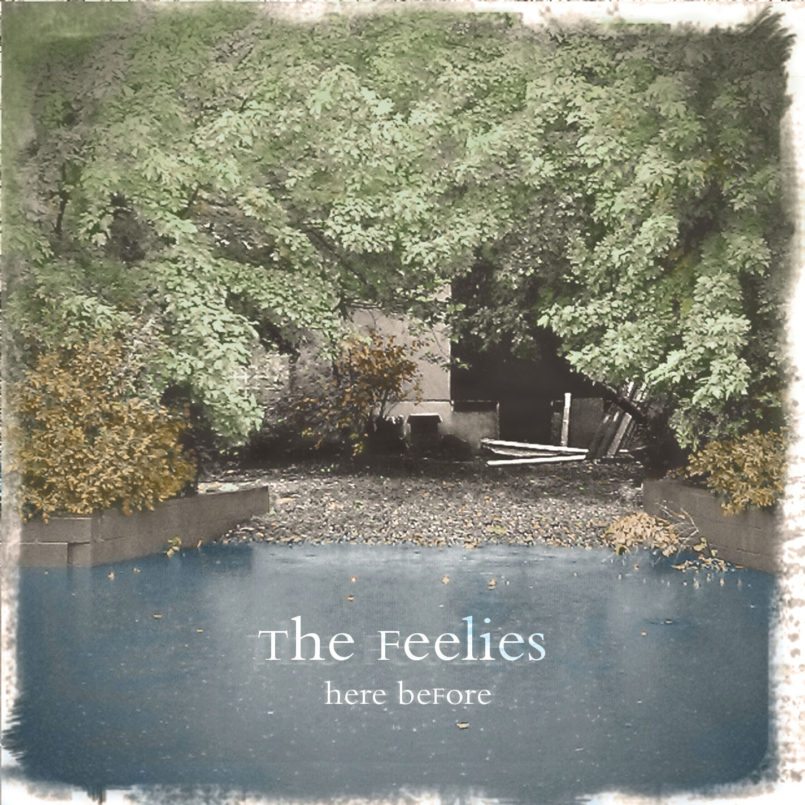

Here Before (2011)

Million: One of the key things is we didn’t stop playing on bad terms. And Glenn and I stayed in touch because we’d always get offers or interest for songs that we had recorded, whether it was something for a film or a commercial or whatever.

Mercer: There was some licensing request that needed to be addressed. I forget exactly what it was, but I called [Bill] up and found out that he had been coming up to New Jersey [from Florida] with his son who was attending Princeton at the time, so I casually said, “Well, if you want to stop over and jam anytime…” You know, threw that out there. Said, “It doesn’t have to be for a show—we can just play to play.” We kind of kept in touch at that point. But it really took another five or six years, at least.

Million: I was actually pretty reluctant [to reunite and open for Sonic Youth in 2008] because I thought, “If we do this and it doesn’t sound right or feel right, then we’ve made this commitment to play—and it probably wouldn’t be good.” But on the other hand, my thinking was, “If we don’t make a commitment, we’ll probably hold off for a lot longer.” So we agreed to do the show and, you know…we’re still playing. It’s not any more complicated than that. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 4. You can download or purchase the magazine here.