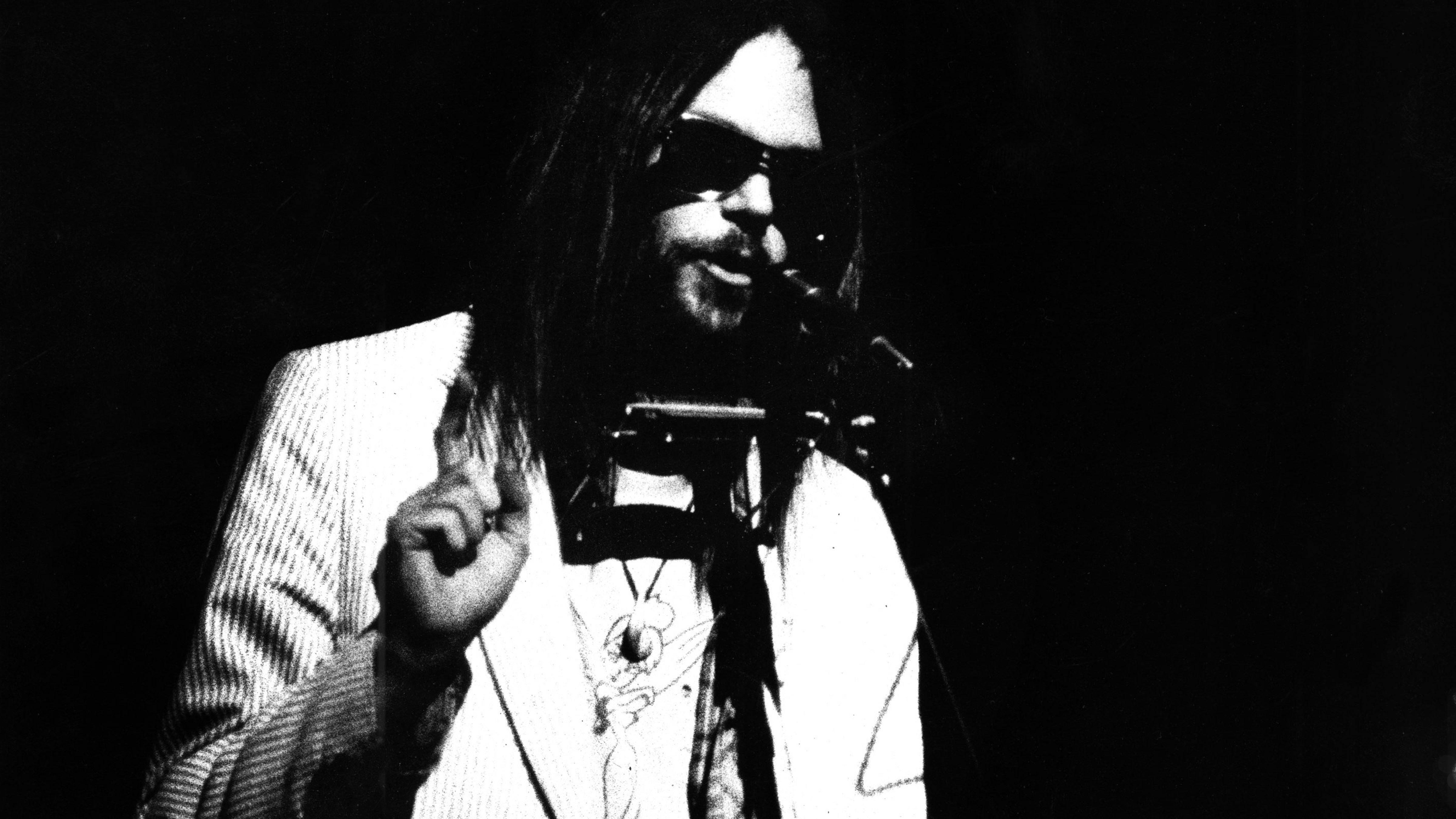

Neil Young was once a star. Riding high on the success of 1972’s Harvest, which was and still is his only album to top the Billboard 200, he was booked to a lengthy sixty-two-date tour and hired a private jet to ferry he and his band, The Stray Gators, from city to city, where they’d ostensibly play “Heart of Gold” and “Old Man” and “After the Gold Rush” to hushed, reverent arena crowds. Neil had a batch of new songs he was working on and decided he’d not only test them out on the road but record the results.

It didn’t go down so smoothly. When the Gators commenced rehearsals on Young’s Broken Arrow Ranch, Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten showed up so strung out he was unable to play. Neil sent Whitten home to LA, where he overdosed and died that night.

Whitten’s death hung like a pall over the tour—and indeed over much of the rest of Young’s life. Still faced with the responsibilities of superstardom, he headed out on the road and into the black. What came of that initial tour and the time immediately thereafter are three of the most complex and uncomfortable rock and roll records ever recorded. “[‘Heart of Gold’] put me in the middle of the road,” he famously wrote in the liner notes of 1977’s anthology Decade. “Traveling there soon became a bore so I headed for the ditch. A rougher ride but I saw more interesting people there.”

On September 6, those three records—Time Fades Away, Tonight’s the Night, and On the Beach—will be reissued on vinyl, along with 1975’s Zuma; it’s the first time Time Fades Away will be available for individual purchase since its initial release forty-three years ago. In honor of this milestone, today we look back on The Ditch Trilogy.

Time Fades Away (1973)

Even if Danny Whitten had been alive to partake in it, the 1973 tour with The Stray Gators would have generated enough chaos of its own—everyone was on coke and pills; Neil’s relationship with Carrie Snodgress was crumbling; he resented the overpaid band; pianist Jack Nitzsche was perpetually drunk and one night pissed on Neil’s hotel room floor; Graham Nash and David Crosby were brought in to help and ended up alienating the others; etc.

This is not the ideal environment for making a new record. But the live recording project persisted, and six months after the tour wrapped—more than enough time for the album to be scrapped—Time Fades Away was released. If you own a copy now, you either bought a very limited Record Store Day edition in 2014, or you have one of those mid-’70s pressings. It has never been issued on CD. It’s only available digitally via Pono. It is, to put it lightly, not held in high regard by its creator: “it’s the worst record I ever made,” Neil told an interviewer in 1987.

And he’s partly right—Time Fades Away is arguably the least appealing of Young’s early records (though it’s worth noting that he was touring Landing on Water when he made that claim), and given its genesis, it’s not surprising that he’d rather not deal with it. It’s a sad, broken, angry, and tearful collection of music performed for an indifferent audience that paid to hear “The Needle and the Damage Done” but only got the damage. It lacks the ramshackle charm of Tonight’s the Night and the formal elegance of On the Beach.

“[Time Fades Away] is the worst record I ever made.”

That’s also what makes it imminently compelling. “As a documentary of what was happening to me,” Neil told that same interviewer, “it was a great record.” And it’s hard to fault him there. It doesn’t take a very close listen to Time Fades Away to picture the solitary figure, alienated from his bandmates and his wife, confronted with the logical end of his own lifestyle, playing for the biggest crowds of his life and wanting none of it. His longing for an escape is palpable; it lurches off of these songs like an uneasy steam. The first two tracks reference his Canadian upbringing, and the fourth, “L.A.,” doesn’t exactly paint a sunny portrait of his adoptive home. Between them, he calls someone—or himself—“The Great Pretender.”

But the album finds its emotional—and artistic—high point in the five-and-a-half slow-burning minutes of “Don’t Be Denied,” arguably Time Fades Away’s one certifiable classic and one of the few songs Neil would continue to play after the initial tour. It, too, finds him journeying through the past, all the way back to his family’s move from Eastern Canada to Winnipeg, through the formation of his first band, his move to California, record deals, financial success, stardom. “Don’t be denied,” he wails over a lukewarm rave-up. It’s difficult listening, but unlike much of the rest of Time Fades Away, it’s played with a momentary open-heartedness; it’s the only time you get the sense that all five of the players on stage are suffering, and that they’re united in their expression. It’s one of the purest portraits of blunted mourning that exists in popular music.

Still, it’s an outlier on the most alienating of a trio of records about alienation. While the quotation that gives The Ditch Trilogy its name sounds like the kind of inspirational countercultural mantra you’d find in a yearbook, Time Fades Away, like the two records that follow it, make you wonder whether he met anyone else in the ditch at all. — Marty Sartini Garner

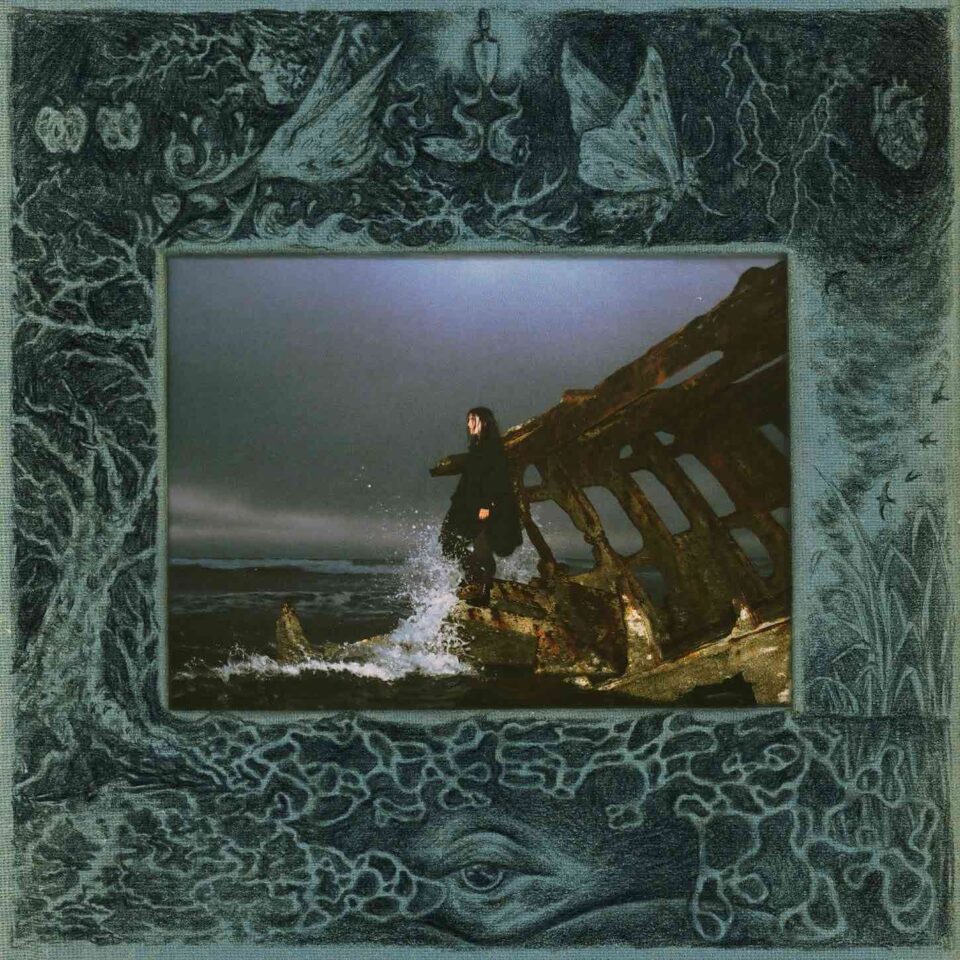

Tonight’s the Night (recorded 1973, released 1975)

Coming off the Stray Gators tour, Neil Young was in rough shape. While the band was still reeling from the loss of Whitten, beloved roadie Bruce Berry overdosed and died. Death was everywhere, looming over the Santa Monica Mountains with news of a brutal double murder in Topanga Canyon dominating headlines. So Neil decamped to a cobbled-together studio with producer David Briggs, pedal steel player Ben Keith, guitarist Nils Lofgren, and Crazy Horse rhythm section Billy Talbot and Ralph Molina, and he cut a record reflecting the rot in the air. He’d call it Tonight’s the Night, named for the song that opened and closed the album, and he envisioned it as a corrective to the slickness all around him—the pop success he’d enjoyed with Harvest and his associations with California’s easy-living country rock heroes—a loose, flailing album fueled by grass and tequila and dread.

Upon completion, most of Neil’s peers hated it (“Why are you doing this to yourself?” asked Glenn Frey of the Eagles, according to Jimmy McDonough’s essential Neil bio Shakey). His label, Reprise Records, was baffled, delaying its release for nearly two years, making the record’s placement in The Ditch Trilogy complicated: it was recorded before On the Beach, but it was released after, representing the beginning of Neil’s ravaged period as much as its end.

“Why are you doing this to yourself?” — The Eagles’ Glenn Frey

The goal was a true capturing of a moment. Young refused to rehearse the band in advance, recording live and refusing overdubs and other fixes, and thus the songs of Tonight’s the Night often fall together with a tentative elegance, each member of the ensemble listening to the others in a desperate attempt to keep it together. You can hear the balancing act in “Speakin’ Out,” where Lofgren begins a solo, delicate and overdriven, stepping out of the way as Keith’s pedal steel rises to match it in intensity, or in the heavy drone of “Albuquerque,” where it’s clear the guys don’t quite have their harmonies down and are searching for the right notes. A record built on interplay, it always allows room for disintegration: on “World on a String,” Young’s Broadcaster grinds until it almost seems to crumble.

Ask most Neil fans, and they’ll tell you Tonight’s the Night is one of the darkest albums in his discography, and while there’s no escaping its spookiness, its vitality can’t be denied, either; it links Young’s bummers to joyful creation. It’s no accident that its most celebratory song, a live recording of Whitten himself singing “Come on Baby Let’s Go Downtown” a few years earlier, is a cheeky ode to scoring exactly what would take him out.

As an elegy, Tonight’s the Night is dubious, but as an Irish Wake, it excels, pulled between heartbreak and raucous glee. According to Neil, original copies were packed with a bag of glitter that would spill out on the listener from the jacket, which bore a washed-out image of Young looking utterly deranged, printed in white on a black sleeve. Per his direction, artist Gary Burden designed the album cover to be printed on blotter paper that would age quickly and be prone to falling apart completely. And that’s how Tonight’s the Night endures, as a thing that shouldn’t exist, its arrival stalled, its grace tempered by its ragged improbability. — Jason P. Woodbury

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uopmr4sBNM4

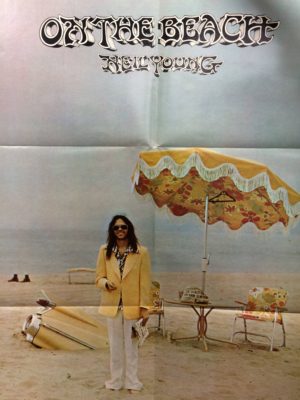

On the Beach (1974)

Much has been made of Neil Young’s gorgeous tumble into the ditch, but not nearly enough has been made of his unlikely crawl back out of it. Part of that is due to the wonky timeline, I suppose, and part is due to the fact that his post-ditch releases never really were on the straight and narrow anyway (something innocent in his first four albums was lost when Danny Whitten and Bruce Berry died—something that to this day he’s never gotten back). But considering the fact that the “Hello Waterface” note from Tonight’s the Night was described by Neil as being “a suicide note without the suicide,” it cannot be stressed enough how far down he initially tumbled. This wasn’t a ditch—it was a black hole.

On the Beach is an incredibly bleak record, yes, but I dare anyone to listen to it after Time Fades Away and Tonight’s the Night and not feel the wheels starting to turn again. On the album cover, for instance, there’s Neil—past the car in the proverbial ditch, past the booze, and past the newspaper with the depressing political headline (relevant much?)—up and facing the horizon on what appears to be an incessantly gloomy day. It’s not cheerful—but it’s hopeful. Just take a look at that shit-eating grin on the promotional poster if you want to see what he looks like on other side.

On the Beach is an incredibly bleak record, yes, but I dare anyone to listen to it after Time Fades Away and Tonight’s the Night and not feel the wheels starting to turn again. On the album cover, for instance, there’s Neil—past the car in the proverbial ditch, past the booze, and past the newspaper with the depressing political headline (relevant much?)—up and facing the horizon on what appears to be an incessantly gloomy day. It’s not cheerful—but it’s hopeful. Just take a look at that shit-eating grin on the promotional poster if you want to see what he looks like on other side.

Of course, smiles can be deceiving. “Walk On,” one of the most outwardly optimistic songs that Neil has ever written, is actually said to be a response track (a diss track, if you will) to his more-public-than-personal feud with Lynyrd Skynyrd. And that’s just the tone at the start of the album. From there, the theme is quite literally the blues, with ol’ Neil getting into the Manson Family and the death of the ’60s (“Revolution Blues”), the soullessness of the oil industry (“Vampire Blues”), and the slow, bitter dissolution of CSNY (“Ambulance Blues”). It seems like by the time he pulled his head outta that ditch—or had his head come through the other side of that black hole—what Neil found was a scene of pure bedlam. And with that in mind, the smile on the poster might not be the smile of someone on the verge of contentment, but rather of someone on the verge of madness. Either way, that’s still an improvement from total disrepair, right?

Something that strikes me as funny about On the Beach is that, despite it being one of the greatest and most talked-about albums ever, it still comes up third in the all-knowing eye of Google behind the eponymous Stanley Kramer film from 1959 and the Nevil Shute novel from 1957 upon which the movie was based. Fair enough, though. Both works are classics in their own right, and given their shockingly blunt apocalyptic themes, they always did seem like they might’ve been intentional siblings to the album in the first place (tell me you can’t imagine Gregory Peck whispering the line, “An ambulance can only go so fast”).

But the world didn’t end in 1974. Not in the slightest for Neil, anyway. As it turns out, he was just arriving at the exact midpoint of his legendary tear from 1969 to 1979, and there were many, many more miles to travel. Still are, in fact. He just has to be careful to mind them yellow lines. — Nate Rogers

Read our FLOOD 4 cover story on Neil Young: All Alone the Captain Stands.