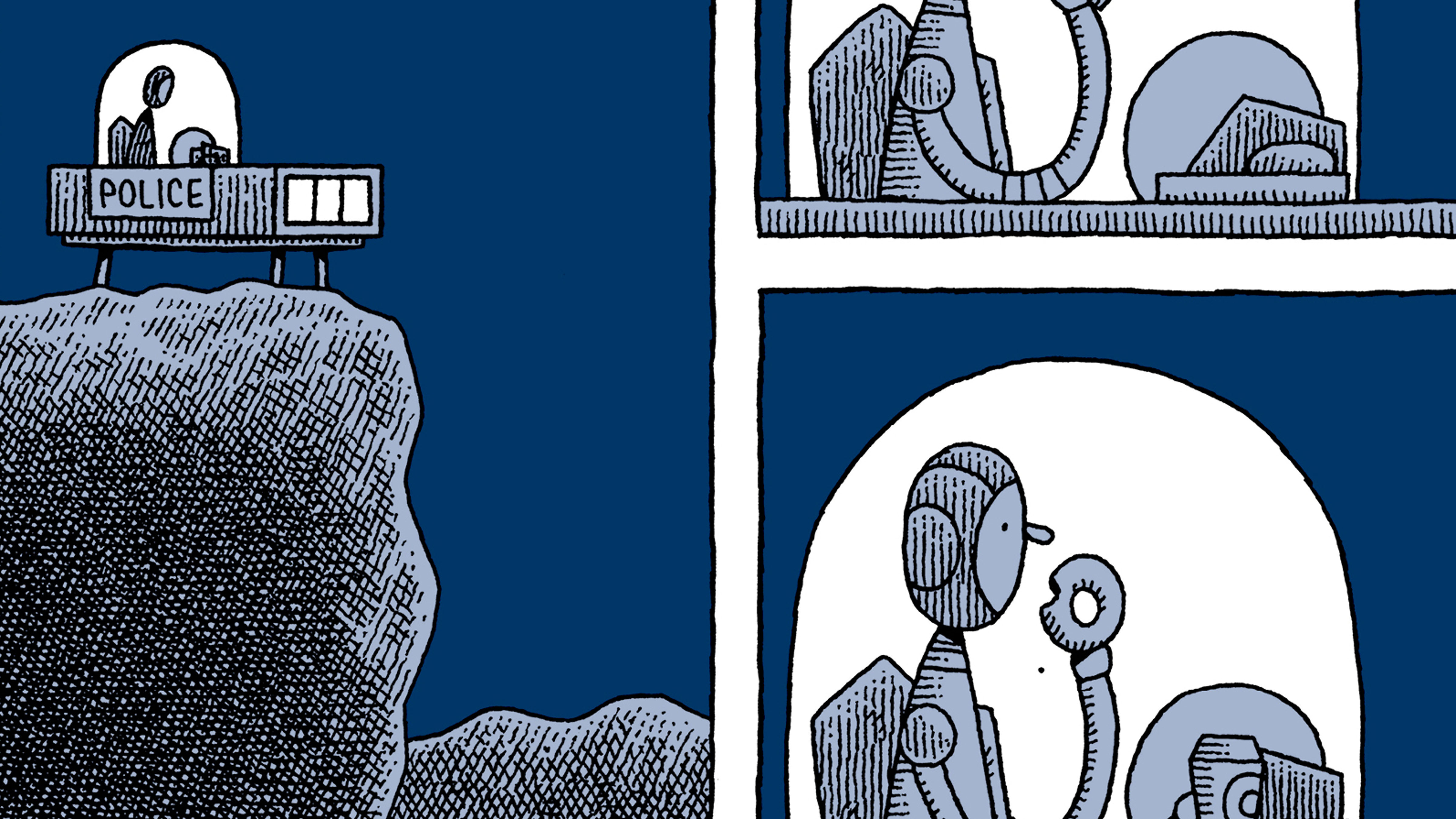

Tom Gauld’s latest graphic novel—or “graphic novella,” to borrow his term—is as slight and lovely as its themes are ponderous and difficult. This is a book about alienation and loneliness that features a mildly depressed cop on the beat of a very quiet moon. It co-stars a dog, a robot, and a lunar coffee shop on its last legs. And nothing much happens because there’s nothing much to do. But the book’s modesty belies its depth. This is a small book with a big heart, and it sticks with you. We were lucky enough to talk with Tom Gauld recently (via e-mail, as is only fitting) about why this character matters, where he came from, and what it all means. He was kind enough to share a few exclusive pages of Mooncop with us, as well.

I was reading about RoboCop recently, and I was reminded of the hilarious fact that the original idea sprang from a discussion of Blade Runner and “robot cops.” The Mooncop concept is similarly guileless, and it makes me curious about how this idea came about, and what you were consuming and thinking about at the time.

I was reading about RoboCop recently, and I was reminded of the hilarious fact that the original idea sprang from a discussion of Blade Runner and “robot cops.” The Mooncop concept is similarly guileless, and it makes me curious about how this idea came about, and what you were consuming and thinking about at the time.

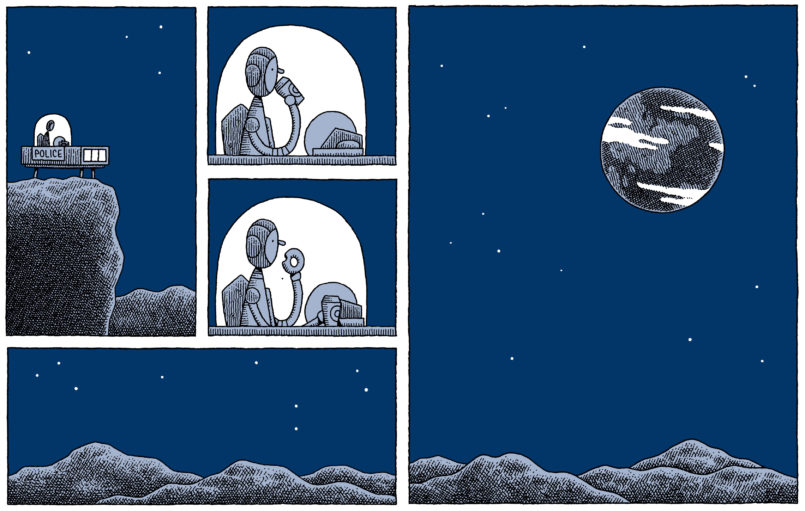

The spark for the Mooncop idea was a toy car I saw on the Internet. It dated from the early ’60s, was made of tin, and had a glass dome on top, in which a robot sat firing a huge cannon. The car was displayed patrolling the moon, with the earth in the sky above. It seemed funny and sort of tragic that the toy suggested that not only would people live on the moon, but that there would be enough crime to warrant armed robotic guards with blaster cannons. It seemed to have a very dated optimism about space and technology—and it made me feel a bit sad to reflect that in fact nobody’s been to the moon for decades. I began to think about the lonely robot patrolling an empty moon and the story grew from there. Somewhere along the line the robot turned into a human policeman.

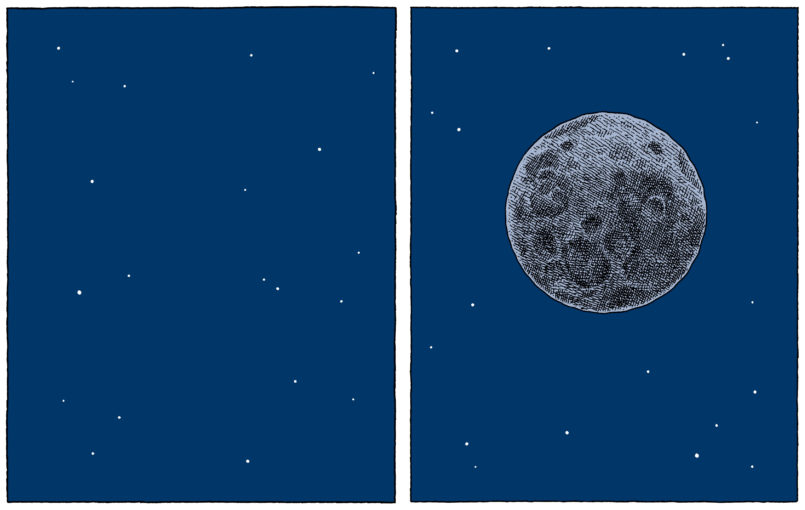

The opening pages of the book take place in almost complete silence, and nobody speaks until page nine. Can you talk a bit about the importance of silence in your book, and what it is that you think silence “does.”

In the case of those early pages, I wanted to give the reader a chance to take in the atmosphere of the moon visually, in a more open-ended, mysterious way than if it had dialogue or narration or even sound effects. Also, the moon is a pretty silent place and in the story it’s quieter than the characters are used to, so it seemed to fit.

In general, I like moments with no text in my stories. I feel it slows things down and gives the reader time and space to think about what’s happening. I have to trust the reader to spend a little time on the silent panels and not just to skip to the next bit of dialogue. That worries me a bit sometimes, as I think people who don’t often read comics have more trouble with reading pictures than words. So I try to get the words-to-picture balance right.

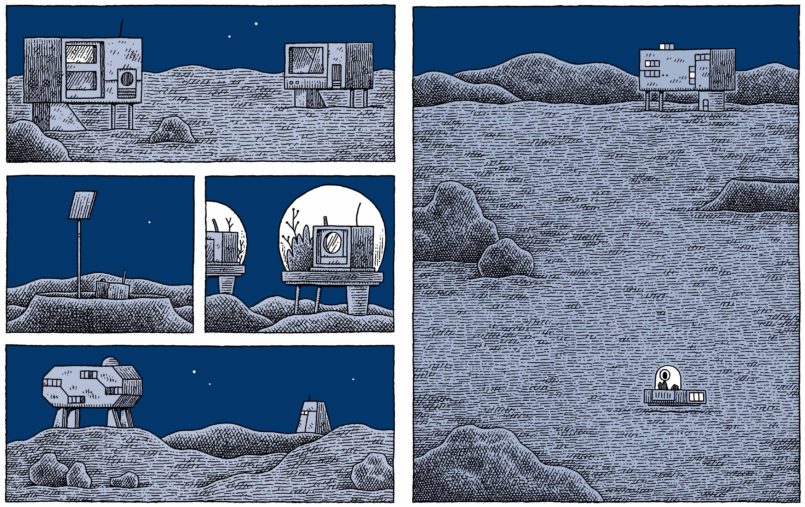

On a related note, there is so much that happens off camera, so to speak, and I think that’s one of the things that makes this book feel so propulsive, despite the fact that it’s largely focused on mundane details. I’m thinking especially of page fifty-four, where instead of seeing what the mooncop is working on (a transfer request) we only “hear” his typing. Can you talk me through your thinking on that page?

One of the things I enjoy in making comics is giving the reader little gaps to fill in themselves. Filling in the gaps between panels is how we read any comic, but if the gaps are a bit bigger I think it’s more pleasurable to make the jump. I know I find this reading other people’s comics. Of course, you can’t make the leaps too big or it just gets confusing. In the typing scene I was intentionally stretching out the moment to underline the pointlessness of the task. Timing is important to comedy, and comics are a really good place to play with time.

Yes indeed. And page sixty-four contains another hilarious example of a joke happening between the panels, rather than within them. Is it important that the mooncop has no name beyond his title? That seems to put him in the tradition of, say, Josef K. Or is that going too far?

Not having a name hopefully helps suggest that the mooncop doesn’t have enough of an identity outside his job. I quite often find that I’ve written a comic and few of the characters have names. I like the minimalist, iconic, stock-character feel of nameless characters.

I’m really interested in the themes of loneliness and alienation that seem to be at the center of Mooncop, because those are themes that tend to be taken very seriously. I’m thinking of movies like L’Avventura, Solaris, and Lost in Translation even. Those movies seem to be dealing with Alienation with a capital A, whereas Mooncop’s sense of alienation seems more… human-sized (ironic, given the cosmic setting). I wonder if you could talk a bit about that, and about how humor factors into your treatment?

“The mooncop isn’t crippled with depression, he just feels a bit lost, a bit stuck, a bit flat.”

The mooncop isn’t crippled with depression, he just feels a bit lost, a bit stuck, a bit flat. These are all things that I feel from time to time and I imagine most other people do too. This isn’t a recipe for a thrilling tale, but I hoped that the contrast with the moon setting—and our cultural ideas about sci-fi excitement—would be interesting.

I don’t think I’d know how to write a comic without some humor in it and I think that through humor I can tackle things that I’d find difficult to get at otherwise. Most of my favorite writers are funny, even if they’re also talking about serious things.

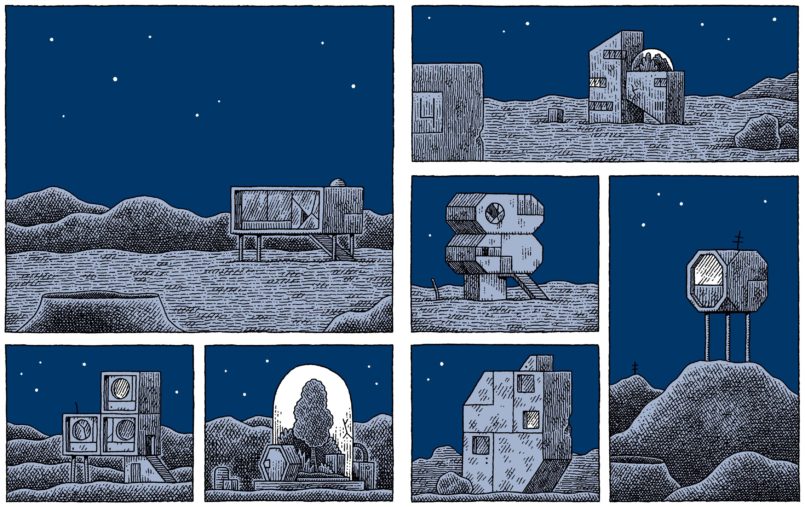

I really liked the aesthetic of your moon colony. How did you settle on that particular style of architecture, and what futuristic vision/s did you take your inspiration from?

I spent a lot of time on the design of the moon colony. I wanted it to be a mix of the semi-realistic NASA-inspired design from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and a more over-the-top tin toy/Jetsons feeling.

Another major inspiration was British modernist architecture from the ’60s, much of which I love. I think that they had much of the same utopian, pro-technology feeling as the space race. If you see designs of concrete housing schemes from the ’60s, they’re so optimistic and forward looking, but like the moon colony, they’ve (generally) not aged very well.

The mooncop’s apartment building is based around a real ’70s Japanese tower block built out of cuboid prefab units called Nakagin Capsule Tower. It’s wonderfully retro-futurist but is also decaying and semi-abandoned.

There are hints of how this moon colony came to be, why these people are here, and what they might have to look forward to back on Earth, but not much more than hints. How much of a backstory did you create for this world and its characters, or how much of a backstory do you think it’s necessary for them to have in order for them to feel alive?

There are hints of how this moon colony came to be, why these people are here, and what they might have to look forward to back on Earth, but not much more than hints. How much of a backstory did you create for this world and its characters, or how much of a backstory do you think it’s necessary for them to have in order for them to feel alive?

I enjoy the world-building aspect of making comics and gave a lot of thought to the biblical-style world I used in my first book, Goliath. But the moon colony was much more work. I wanted it feel cohesive and believable, but I also wanted to play with ideas from both history and science fiction. 2001: A Space Odyssey was a visual influence, and it was also my model for the optimistic beginnings of the moon colony that never appear in the story, but are hinted at. Likewise, I wrote more conversations between the characters than appear in the book. The mooncop had a long phone call with his mother that helped me figure out some things, but in the end that seemed too explain-y for the story.

“I think stories all have their own correct length and one just has to find it and accept it. I’d certainly not want to overstay my welcome.”

We tend to think about books as though their size is almost predetermined, but your book is one where the relative shortness seems important and intentional. Is that true? And if so, how do you think the relative brevity of this comic benefits your material?

At one point I did try to make Mooncop a bit longer, as I thought that the publishing world would prefer a fatter book. But everything I tried to add just made it longer and not better. I think stories all have their own correct length and one just has to find it and accept it. I’d certainly not want to overstay my welcome. Mooncop should probably be called a “graphic novella,” but that sounds oddly pretentious despite being just a statement about length.

What’s next for you?

I’m mulling over ideas for a new graphic novel but I haven’t properly started on anything. I’m continuing to make short weekly cartoons for The Guardian and New Scientist, and my next book will probably be a collection of the cultural cartoons from The Guardian.

One last question: Which came first, the moon or the mooncop?

Some of my very first cartoons were about two bickering astronauts on the moon, and I’ve wanted to do a sci-fi story for a few years now. In 2001 I bought a book called Full Moon that contains a collection of the stunningly beautiful photographs taken by the Apollo astronauts. That book still fills me with awe when I look at it. I’ve been looking for a way to set a story on the moon for years but couldn’t think of anything suitable before this. FL