“Becomes the fiddlestick. What do I care whether it becomes me or not? I don’t wear black because it becomes me…I wear mourning because it corresponds with my feelings.”—teenager Nannie Haskins, upon being told that the mourning attire she wore for her brother was “becoming” (1863)

“I wear black on the outside / ’Cause black is how I feel on the inside.”— The Smiths, “Unloveable” (1986)

There are certain topical art exhibitions that can feel more like a tourist attraction (cough, recreationofCBGBsbathroom, cough), and less like an informative, creative, visually stimulating summation of an era.

But others hit the coffin nail on the head.

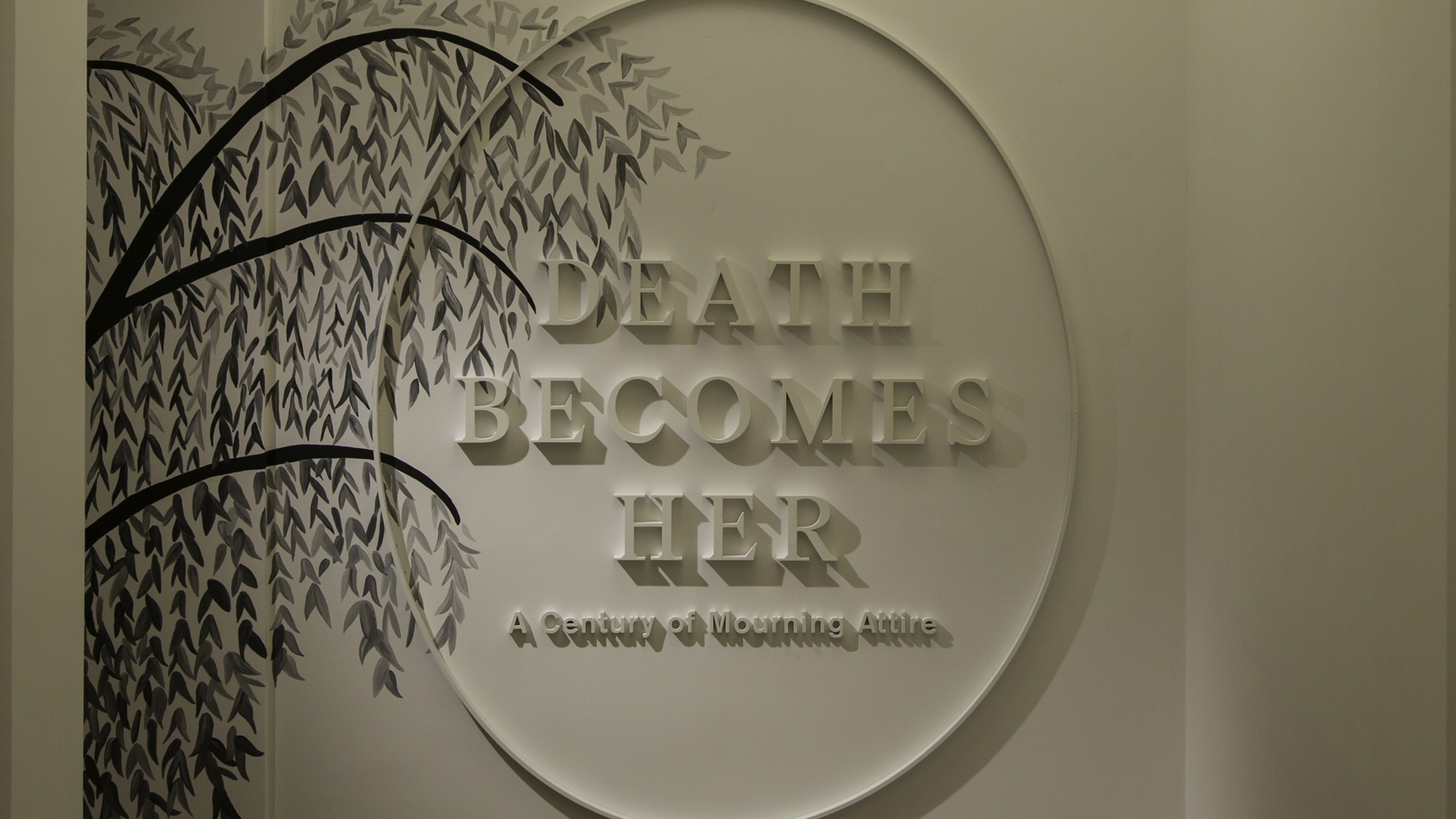

Gallery View

Anna Wintour Costume Center, Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch

Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The first fall exhibit the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Anna Wintour Costume Center (formerly Institute) has hosted in seven years, the cheekily titled Death Becomes Her focuses on mourning attire and practices from 1815–1915. Color me morbidly excited because, as Moz says, “If I seem a little strange, that’s because I am.”

But in my defense, fascination with death is nothing new. Nor is the exploitation of death: as Death Becomes Her informs me, mourning was about more than feelings. Even in the 1800s, stores like Jay’s of London and James McCreery & Co. capitalized on mourning attire. Look!: Fashion and death can co-exist! they proclaimed. Indeed, from the five stages of mourning and the appropriate dress for each one, to the classism of fabrics (a black that didn’t fade signaled high class), the business of death was both monarchial and capitalistic. See Queen Alexandra’s ostentatious evening mourning gowns, worn while the masses sported dull silk.

Evening Dress,1902

Worn by Queen Alexandra (British, born Denmark, 1844–1925)

Black silk tulle, mauve silk chiffon, purple sequins

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Miss Irene Lewisohn, 1937 (C.I. 37.44.2a, b)

Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Karin L. Willis

Despite this, mourning attire was a way for the bereaved to cope with and express their grief. The Victorian hair art (where a lock of your loved one’s hair was preserved forever in a broach, ring, or frame) on display is downright ritualistic verging on fetishistic, as are the mourning portraits—including one draped in a black cloth. If you lift it, you can view the image of a child who looks blissfully asleep.

But wait, what about the beautiful dresses of the era, the main focus of the exhibit? Well, take a look at the pretty pictures here or visit the Met; you really don’t need me expounding on the cut or the fit or the fabric (even though the moiré silk was, um, to die for). While ostensibly about fashion, Death Becomes Her is more about the nature of death itself and how society copes. In the modern age of social media, pandemics, and war, talk of death is oddly whitewashed or avoided altogether. Mourning is a private affair. You’re expected to go out into the world and say, “Hey, thanks, but I’m good now.” Whereas in the Victorian era, whilst dressed in black everyone knew that, like both Nannie Haskins and Moz, it was how you felt on the inside.

Not always, though. The main gallery also features quotes on the walls from notables of the time, like this one from Julia Ward Howe: My mourning has been quite an inconvenience to me, this summer. I had just spent all the money I could afford for my summer clothes, and was forced to spend $30 more for black dresses. The black clothes, however, seem to me very idle things, and I shall leave word in my will that no one shall wear them for me.

Charles Dana Gibson (American,1867–1944)

Illustration, 1900

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas J. Watson Library, Gift of Mrs. John Barry Ryan

Adding more wry humor to the exhibit, a series of Charles Dana Gibson illustrations from Life magazine circa 1900, are entitled “A Widow and Her Friends”—“friends” referring to those of the male persuasion. Even the title of the exhibit gives us a wink and a nod: not only does the Victorian woman become a facsimile of death when mourning, but she looks damn good doing it, too.

Really, it’s all very Lydia Deetz: death can be tragic, and death can be humorous. So gather up your ghosts, don your crepe, and don’t forget to grab a souvenir postcard on the way out. FL

- Mourning Ensemble,1870-1872 Black silk crape, black mousseline The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Martha Woodward Weber, 1930 (2009.300.633a, b) Veil, ca. 1875 Black silk crape The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Roi White, 1984 (1984.285.1) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Karin L. Willis

- Evening Dress, ca.1861 Black moiré silk, black jet, black lace Lent by Roy Langford (C.I.L.37.1a) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Karin L. Willis

- Mourning Dress,1902-1904Black silk crape, black chiffon, black taffetaThe Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of The New York Historical Society, 1979 (1979.346.93b, c)Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Karin L. Willis

- Mourning Dress (Detail), 1902-1904 Black silk crape, black chiffon, black taffeta The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of The New York Historical Society, 1979; (1979.346.93b, c) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Karin L. Willis

- Henriette Favre (French) Evening Dress, 1902 Worn by Queen Alexandra (British, born Denmark, 1844–1925) Mauve silk tulle, sequins The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Miss Irene Lewisohn, 1937 (C.I. 37.44.1) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Karin L. Willis

- Evening Dress,1902 Worn by Queen Alexandra (British, born Denmark, 1844–1925) Black silk tulle, mauve silk chiffon, purple sequins The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Miss Irene Lewisohn, 1937 (C.I. 37.44.2a, b) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Karin L. Willis

- Spectators at Ascot, including the Marchioness of Camden. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

- Charles Dana Gibson (American,1867–1944) Illustration, 1900 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas J. Watson Library, Gift of Mrs. John Barry Ryan

- Charles Dana Gibson (American,1867–1944) Illustration, 1900 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas J. Watson Library, Gift of Mrs. John Barry Ryan

- Mourning Parasol, 1895-1900 Black silk, wood, metal, tortoiseshell The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Rachel Trowbridge, 1960 (2009.300.2478) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Henri Bendel (American, founded 1895) Mourning Hat, ca. 1915 Black straw, black silk, plastic, metal The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Frederick H. Prince, Jr., 1967 (2009.300.1577) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Brooch, ca. 1850 [Top] Gold, jet, pearls, crystal, hair The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Susan and Jon Rotenstreich Gift, 2000 (2000.557) Tiffany & Co. (American, founded 1837) [Bottom] Brooch, 1868 Gold, pearls, black enamel, hair The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Susan and Jon Rotenstreich Gift, 2000 (2000.556) Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Fashion Plate, 1824 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Costume Institute, The Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library; Gift of Woodman Thomson

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center, Stairwell Entryway Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center, Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center, Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center, Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center Lizzie and Jonathan Tisch Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Gallery View Anna Wintour Costume Center Carl and Iris Barrel Apfel Gallery Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire is on exhibit through February 1, 2015 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Anna Wintour Costume Center.