The canon is hardly foolproof. It’s generally not wrong—no one’s saying there’s any argument to be made against Sgt. Pepper’s or The Godfather—but it is incomplete. Sometimes it’s underexposure and sometimes it’s overexposure, but for whatever reason, things fall through the cracks.

With that in mind, The Back Pages is a crate-digging, B movie–watching, moldy book–reading column with the intention of offering a hand from the departing ship of the common vernacular. It’s cultural mutiny, from stern to bow. Jump aboard.

Last month marked the thirtieth anniversary of the theatrical release of Down by Law, Jim Jarmusch’s third feature, and in some ways my personal favorite of his films. That’s hardly meant as a knock against more canonical Jarmusch works like Stranger Than Paradise and Dead Man; it’s difficult to choose a favorite in an oeuvre as richly idiosyncratic as his. But there’s an elemental quality to Down by Law that stands out among his films, one that allows its pleasures and profundities to emerge more accessibly—yet no less movingly—than they do in his more widely celebrated work.

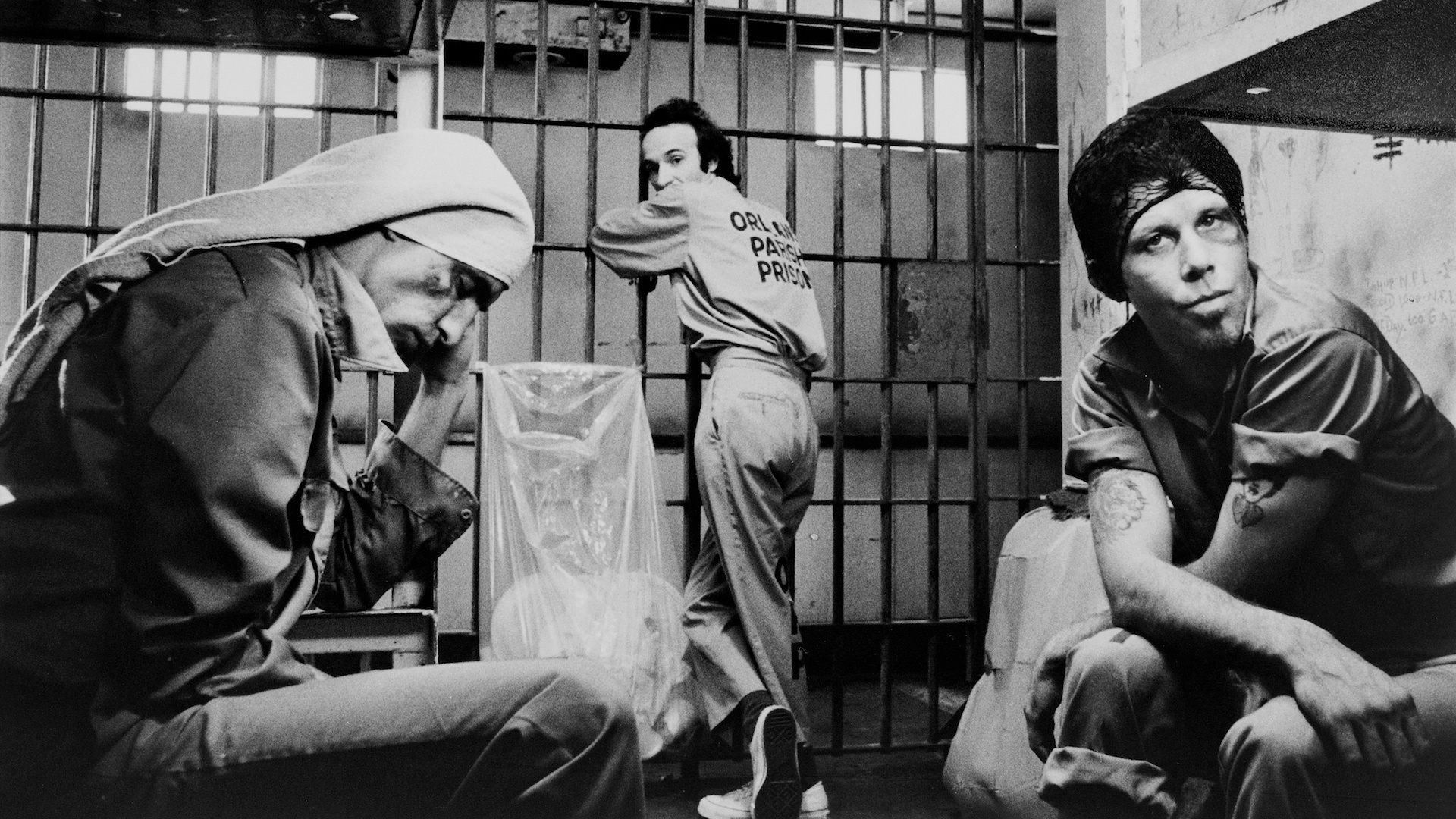

That’s not to say that the film is an outlier for Jarmusch, by any means; in fact, its similarities to his two preceding films—the aforementioned Stranger Than Paradise and 1980’s Permanent Vacation—are such that perhaps it’s no surprise some critics felt that he wasn’t necessarily adding anything new to his vision. The black-and-white cinematography, the vignette-like road-trip structure, the cool deadpan vibe—all were stylistic characteristics that Jarmusch had toyed with before. In this 1986 film, here was yet another oddball trio thrown together and forced to work through their tensions, much like the New York hipster/friend/Hungarian cousin triad of Stranger Than Paradise; in Down by Law’s depiction of New Orleans, we have another startling vision of a wasteland metropolis akin to the alienating New York of Permanent Vacation.

Look underneath the familiar Jarmuschian surface quirks, however, and one might be able to glimpse something quite different from its predecessors. Essentially, Down by Law is a parable of two lost souls—a disc jockey named Zack (Tom Waits) and a pimp named Jack (John Lurie)—who are, to some extent, redeemed by their interactions with a third, an Italian tourist named Bob (Roberto Benigni, in one of the Italian comedian’s first international roles). Zack and Jack may be thrown into prison together on false pretenses—both victims of set-ups, arrested for crimes they didn’t commit—but they are still guilty in a certain sense. Both are responsible for their own current unhappiness: Zack with his impractical idealism concerning selling out, Jack by being too passive and self-involved for his own good.

Look underneath the familiar Jarmuschian surface quirks, and one might be able to glimpse something in Down by Law quite different from its predecessors.

Neither of them appear to be living their lives with any particular goals in mind and are simply drifting through the same way Allie, the protagonist of Permanent Vacation, floated through New York. Cinematographer Robby Müller—in his first of a handful of collaborations with Jarmusch—surrounds these nomads with high-contrast, nocturnal black-and-white photography that engulfs them in a portentous sense of doom. Naturally, when both of them are thrown into jail together, Müller’s interiors become brighter-lit and less foreboding—and when Bob joins them, the atmosphere palpably changes again along with the lighting schemes.

The highly extroverted Bob stands in stark contrast to Zack and Jack: he’s filled to bursting with all the curiosity and sense of wonder that Zack and Jack’s jaded selves sorely lack (especially when it comes to trying to learn English, a few phrases of which he’s scrubbed into a notebook he carries around). This is evident not only in his behavior around the two, but also in the literary references he excitedly drops in their company. Bob is especially taken with the poetry of Robert Frost, quoting lines from “The Road Not Taken” (in an Italian translation, natch) on more than one occasion, usually to the amused disbelief of his fellow American prisoners.

Bob’s references to that poem aren’t mere whimsy, however, but a kind of mantra that informs the film’s ultimate “moral,” so to speak. Amid the deadpan comedy, a mood of regret permeates Down by Law, driven by a paralyzing sense of loss felt about the roads the characters themselves haven’t taken. In a sense, the film is all about these people finding their way back on a path of embracing life again, taking an active role in their own happiness. Not that Jarmusch is sentimental about it, of course. Though Bob—spoiler alert!—finds his own way toward a happier future when he encounters a fellow Italian named Nicoletta (Nicoletta Braschi, who would later become Benigni’s real-life wife) and immediately falls in love with her, Down By Law leaves both Zack and Jack in a more ambiguous state; both of the Americans, who have escaped from jail, are on the run, but at least now they have the possibility of a fresh start.

But it’s the way Jarmusch visually evokes this brand-new world for Zack and Jack that’s not only memorable but also deeply moving. It’s a wide shot of two diverging paths in the forest, the duo standing at the foot as they tentatively say goodbye. In other words, it’s Robert Frost’s poem made visual. In the context of this film, however, it resonates with a sense of wide-open possibility for these two, especially as both paths lead to seemingly nowhere in particular. It’s moments like these that give lie to the popular conception of Jarmusch as a hipster ironist; Down by Law offers perhaps his most direct demonstration of the emotional depths he’s capable of plumbing beneath the cool surface exterior. FL