A flamboyant Missourian director has a vitriolic meltdown when his community theater production is denied an additional $100,000 in funding. The son of a legendary music producer questions the dimensional differences and relative safety of a memorial concert’s “stagecraft.” Meanwhile, the drummer for a hard rock band dies mysteriously in a bizarre gardening accident. And the color commentator at a prestigious dog show will not stop talking about baseball.

What do these situations have in common, you ask? The answer is that they all coexist in the improvisational universe of Christopher Guest, the gifted comedic facilitator whose films are fueled by the talented and close-knit troupe of actors he has been working with for more than a quarter century. Counted among its core members are Bob Balaban, Ed Begley Jr., and Fred Willard, all of whom appear in Guest’s latest project, Mascots. Like its forebears, the film examines a subculture of eccentric characters—in this case sports mascots—who come together in preparation for a major event: the World Mascot Association Championships. Many familiar faces are present (Jennifer Coolidge, Michael Hitchcock, Jane Lynch, Parker Posey) along with a host of fresh ones (Christopher Moynihan, Chris O’Dowd, Zach Woods). Guest himself makes a brief cameo as Corky St. Clair, the diva theater director of Waiting for Guffman fame (“I’ll tell you why I can’t put up with you people: because you’re bastard people”), much to his cohort’s delight.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=swTWozTxQ-E

“Getting to be in the presence of Corky St. Clair is an incredible experience,” says Bob Balaban over the phone.

“I have always loved watching Chris be that character,” Ed Begley Jr. agrees. “It’s really hard not to laugh at him when he plays Corky, especially at the end of the day when you’re all tired and ready to fall apart. Here it is, 2016, and like a starving man I’m just so in need of that wonderful, delicious meal that is Corky St. Clair. To see Corky again is such an elixir and such a gift.”

It’s telling that Guest’s reparatory players are also among his biggest fans. Balaban, Begley, and Willard have no shortage of glowing things to say about their fearlessly deadpan leader, and judging by his repeated casting of them in his films, the praise goes both ways. More than the thematic solidarity that Guest’s films exhibit, it seems their uncanny personnel has truly allowed them to endure. Begley and Willard both appeared alongside Guest as he began to cultivate his signature style playing the daft but endearing guitarist Nigel Tufnel in the 1984 rock and roll lampoon This Is Spinal Tap, which was directed by Rob Reiner and co-written by Guest himself. Willard, the odd man out in the band of misfits, appears as an out-of-touch military officer, and Begley plays the Tap’s ill-fated original drummer whose horticultural demise he cites as a personal addition by Guest.

It’s telling that Guest’s reparatory players are also among his biggest fans.

“He was always very interested in my garden,” Begley says. “So the fact that he put in a bizarre gardening accident, it just opens up your mind as to what happened. The weedwacker? The tiller? It conjures up all kinds of possibilities and images that are funny and interesting.” It’s just the type of idiosyncratic ad-lib that has become the hallmark of a Christopher Guest movie.

Balaban, who had worked with Guest in the late ’70s, would join the troupe on Waiting for Guffman, playing an apathetic musical director. Guffman also marked the start of Guest’s fruitful creative partnership with Eugene Levy, which would yield the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show parody Best in Show, A Mighty Wind’s over-the-hill folk revue, and the dry, jaded look at Hollywood award culture For Your Consideration. Next came the 2013 HBO series Family Tree, which featured O’Dowd alongside longtime Guest collaborator Michael McKean; and now, Mascots.

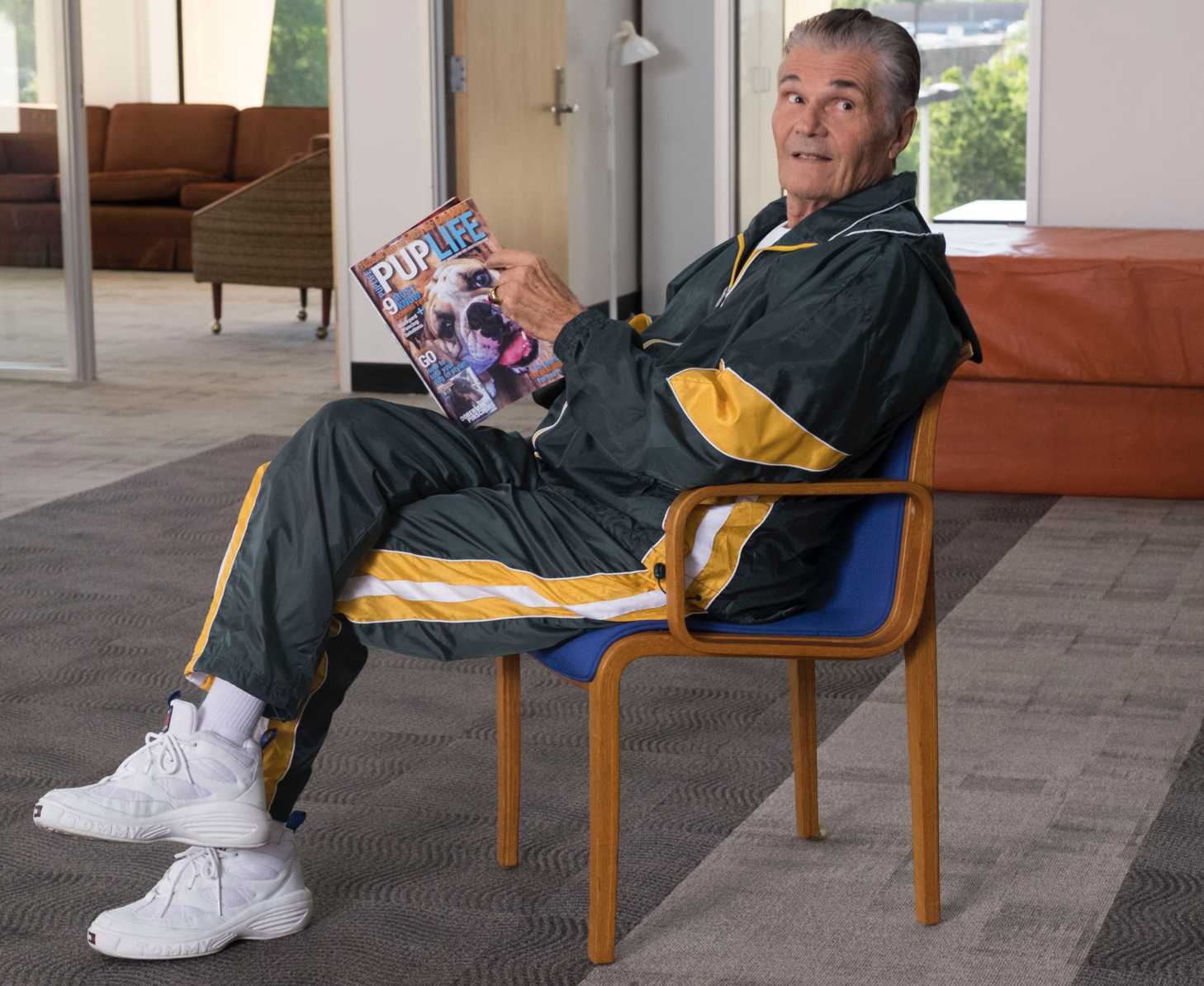

Fred Willard in Mascots

“Chris is very supportive, and I’m always really thrilled when he calls to have me in a new movie,” says Willard over the phone from his Los Angeles home. “It’s going to be something very creative that you can create yourself. You can say something that’s in the back of your mind or go off on a tangent, and you know if it doesn’t work it’ll just not be in the movie. But sometimes [he] surprises you.” In lieu of a typical screenplay, Guest provides his actors with story outlines for his films, laying out situations and character traits that invite further interpretation. According to the director, Willard is particularly well attuned to the freedom of an improvisational format.

“Everyone is watching Fred work,” Guest told Charlie Rose in 2003. “It’s like kids at a party. [He’s] one of the strangest people ever, truly from another place. We roll out entire mags, and Fred will be the one who will say, ‘I’m not finished.’ And everyone kind of looks around, [like], ‘No, we realize you’re not finished, but we actually have to move on.’” Guest paints Willard as a sort of improv unicorn, and apparently finds him so intrinsic to his films that he doesn’t always feel obliged to write him into the script. Such was the case for Best in Show, in which Willard played the aforementioned baseball-obsessed dog-show announcer.

“I thought maybe I’d been cut out of the film and they were just sending me the script as a courtesy.” — Fred Willard

“I had to call [Guest] and say, ‘I’m not in the script,’” remembers Willard. “And they say, ‘Oh, it was a mistake.’ It was a little confusing when I saw my name wasn’t in [there]. I thought maybe I’d been cut out of the film and they were just sending me the script as a courtesy.” Willard’s character, Buck Laughlin, turned out to be one of the biggest highlights of Best in Show. (“I’ve taken a sponge bath in smaller bowls than that!”) In the new film, he plays a former mascot and somewhat disinterested coach who’s a little too self-absorbed to be truly invested in Chris Moynihan’s act as a puffed-up plumber. The first time we encounter Willard’s character, he’s reading a dog magazine, which, much like the reappearance of Corky St. Clair, can be seen as a wormhole running through the Christopher Guest universe. Willard, ever the humble gentleman, considers the detail mere coincidence.

Despite the lack of moral support, Jack the Plumber’s routine proves a rousing success and is remembered by the actors as one of the funniest moments on the Mascots production. “There’s this hysterical scene where he’s unplugging a toilet,” Willard says. “When I read the script, I said to Christopher Guest, ‘This is hysterically funny,’ and he was very non-committal.”

Jennifer Coolidge and Bob Balaban in Mascots

Balaban recalls watching the scene with Jennifer Coolidge as one of the most memorable days on set. “I’m trying to think of the polite word for ‘shit,’” he begins. “The excrement comes out of the toilet and dances for like fifteen minutes. Jennifer and I, as we watched it, instead of talking or whispering about it, we just thought it was literally the funniest thing we’d ever seen.” Though it borders on the grotesque in terms of subject matter, the production value and straight-faced delivery of Moynihan’s performance sell the scene as plausible reality, leaving the viewer a little bit unsure of how to feel. Balaban recognizes this plausibility as an important part of the Christopher Guest experience.

“I’m trying to think of the polite word for ‘shit.’” — Bob Balaban

“To me that’s one of Chris’s many strong suits,” he says. “[It’s] something that probably would be unlikely to happen, and yet, it’s got to be believable or it can’t be in there. He walks a very fine line between being a little too absurd and it [being] actually believable, and I think that’s a very special gift.”

“I’ve never believed in playing a complete jackass,” adds Willard. “Because you always have to feel—even if you are a jackass—you really think you’re doing the right thing and there’s a reason for the things you’re doing. Not just [to] be goofy.” The fact that characters address the camera in an interview format adds to the documentary aspect of Guest’s films, suspending disbelief even more. But please, don’t call it a mockumentary.

Don Lake, Ed Begley Jr., Jane Lynch, and Michael Hitchcock in Mascots

“He hates the term ‘mockumentary,’” says Willard. “He doesn’t like to be pigeonholed, I don’t think.”

Balaban sees the structural through line of these movies as an asset and a source of enjoyment for Guest’s audience. “They’re all different yarns,” he says, “but the way that the yarn is unspooled has a similarity of structure, and I think it’s probably satisfying. It must be fun to have something familiar to expect in the movies.” Mascots follows suit on these terms, but with each new Christopher Guest project, the players and the audience alike are treated to an exploration of an entirely new subculture, and this keeps things inevitably fresh.

“I love all these different worlds that Chris has embraced,” says Begley. “The world of dog shows, the world of show business, the world of small-time theater, and now the world of mascots. I just think they’re great choices at each turn, and I love getting to investigate that world and know more about it. [Guest and his co-writers] really do their research, they learn a lot about it, and then I get to learn more about it.”

Christopher Guest on the set of Mascots

And so, it’s evident that the true glue hidden in the seams of a Christopher Guest movie is simply the man himself. The director is able to articulate what he wants from his actors in a general sense without constricting them. He takes disparate fringe groups and unites them into one bizarro universe that betrays a personal touch. Most of all, he’s earned the trust and friendship of the people he works with. Just ask Balaban.

“I would say that Christopher evolved into this way of doing it, but he was kind of like this from the beginning,” he says. “I think part of his instinct that’s pretty unerringly correct is to more or less let people feel empowered in these situations. It’s really helpful, and the truth is, you are your own engine in these things. It’s definitely controlled by his overseeing of everything. It’s all very fun and relaxed, and it’s a thing I’m very grateful to have been a part of.”

In short, to riff on a classic Nigel Tufnel lick, how much more Guest could a Christopher Guest film be? And the answer is none. None more Guest. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 5. You can download or purchase the magazine here.