FLOOD’s weekly Pop Culture Cure offers an antidote—or nine—to the most upsetting developments of the past week. (Because therapy’s expensive, and entertainment’s not.)

Tom Hanks is game as hell. You have to give him that. He signed a contract to appear as “the world’s greatest mind,” Robert Langdon, in the films based on Dan Brown’s bestselling books, and he is honoring the shit out of that contract. The movie, of course, is ridiculous. (It’s never a good sign when the preview makes more sense if you simply imagine the protagonist is insane.) But the desire to make history relevant and bring the past to life is certainly an honorable desire. And so if we want to enjoy ourselves while edifying ourselves, we’ll just have to avert our eyes from the disaster that is Inferno, and look elsewhere.

The Ghost Map, by Steven Johnson

London in the middle of the nineteenth century was a true marvel. It was home to wealth, innovation, ambition, and some 2.4 million people—making it the biggest city in the world at the time. But it was also, less marvelously, full of poverty and years away from having a proper sewage system. The removal of waste in all its many forms was thus the source of a bustling mini-economy, but since there was no real direction to this effort, people’s drinking water often suffered from contamination. The inefficient removal of waste also meant that the city, as a whole, smelled like shit. Like literal shit.

Consequently, cholera epidemics were not at all uncommon, but since scientists had yet to discover how bacteria could make people sick, many people—including most of the medical and scientific establishment—believed that it was the smell itself, the miasma, that was spreading this deadly plague. The Ghost Map is the story of how a physician named John Snow and a clergyman named Henry Whitehead managed to first identify the real source of the 1854 cholera outbreak and then track it down to a specific pump. The book is a logic puzzle, a treatise on urban planning, a social history, a medical mystery, and, as it turns out, a bestseller as well. Check it out, and then thank your lucky, flushy stars for proper plumbing and sewage.

The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco

The Name of the Rose has to be one of the most unlikely bestsellers of all time. It takes place at a Benedictine monastery; it spends multiple chapters discussing the theological and political issues of the fourteenth century; and it ends on a profound note of uncertainty and anticlimax. But in its favor, The Name of the Rose borrows from one of the all-time great genres (mysteries in enclosed spaces), features one of the all-time great detectives (the monk William of Baskerville), and, most importantly, is just impossible to put down. Because when monks start popping up dead in unlikely places, people just want to know who did it—and, if the answer happens to involve Aristotle, the Inquisition, literary puzzles, library chases, and debates over laughter and the value of learning, then so be it! (The movie adaptation isn’t terrible either.)

Maus, by Art Spiegelman

Maus is, in brief, Art Spiegelman’s attempt to account for how his parents survived the Holocaust, in graphic novel form, using his father as the primary resource, and with animal species standing in for races—so Jews are mice, Germans are cats, Poles are pigs, etc. But there are times when these metaphors show their cracks or reveal their arbitrariness—as when Art visits his own psychiatrist wearing a mouse mask (just like his psychiatrist). Maus is not, in any sense, a straightforward history. The levels of guilt, blame, responsibility, and meaning weave in and out repeatedly, but in the end Spiegelman created something that was much more than just a great comic book. It was a great work of art. It won, among other things, both the Eisner Award and the Pulitzer Prize, and it remains one of the most popular (and saddest, and most thought-provoking, and controversial) graphic novels ever written.

Battle of Algiers, directed by Gillo Pontecorvo

Battle of Algiers was intended as a sort of corrective. It offered an account of the Algerian struggle for independence from the Algerian (rather than the French) point of view. And on that front it certainly succeeded, but as in Lincoln (to take an example from American politics) or the famous thriller Z (to take an example from Greek politics), the director was much more interested in making a movie than in offering a history lesson, and the result is nearly two hours of beautiful, unbearable tension. Although it’s shot in black and white and has a political component, this is not a dated art film. Instead, it does what only the greatest thrillers can do: it refuses to let you go until the credits roll.

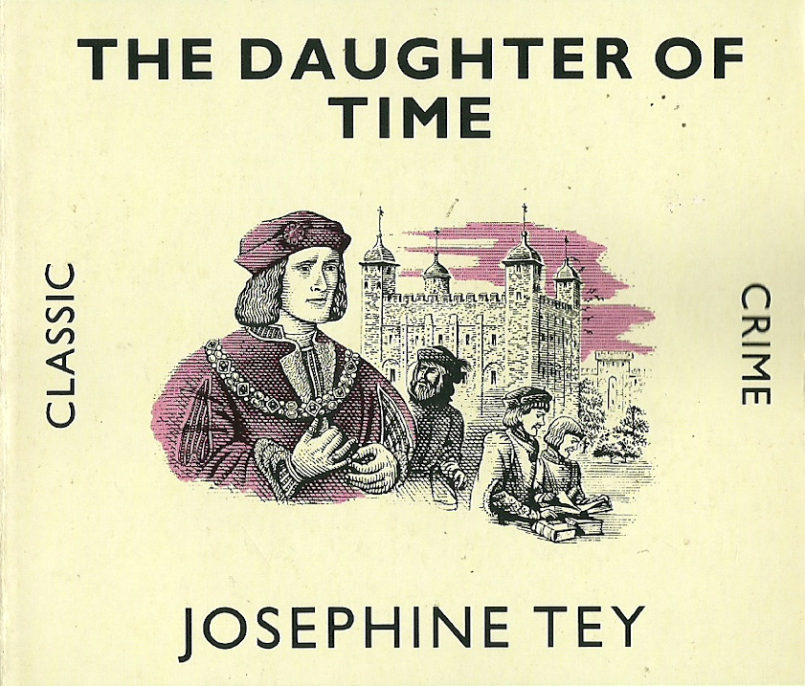

The Daughter of Time, by Josephine Tey

The Daughter of Time, by Josephine Tey

Alan Grant is a Scotland Yard detective of independent means who is, for the moment, bedridden at a London hospital. After considering a portrait of Richard III (the hunchback from Shakespeare’s play, back again), he begins to wonder if this really is the face of a depraved homicidal maniac. With the aid of some friends he begins to investigate the historical record, and without giving too much away, it can at least be said that, if Shakespeare ever convicts you of a crime, it’s going to take one hell of a detective to clear your name. This is one of the most unconventional mystery novels ever written, but it’s also one of the very best.

Wolf Hall, by Hilary Mantel (and the BBC series is also streaming on Amazon)

Before 2009, Thomas Cromwell was a historical figure in need of a serious PR boost. As chief minister to Henry VIII, he was responsible for cutting England’s ties to the Catholic Church, providing for the king’s many marriage annulments (not an easy feat at the time), and persecuting the king’s many enemies. Mantel doesn’t dispute any of these points, but rather allows us to live with Thomas Cromwell and to see him as he may, potentially, have been: as an opportunistic and sometimes brutal man who was also intelligent, curious, and above all, pragmatic. Through his eyes, we get to see a world that is at once very different from our own, but at the same time quite recognizable. It was a very dangerous time to be alive and a very dangerous place to live—but it’s not at all a bad place to visit.

O. J.: Made in America, directed by Ezra Edelman

This is the best documentary of the year, and one of the best movies of the year, full stop, despite the fact that it’s seven hours long and covers a subject that most people would have assumed had already been sufficiently addressed. But this entry in ESPN’s 30 for 30 series manages to take every little thing into account, and somehow addresses almost every pressing topic that America faced in the ’90s—and which still haunt us today.