The universe of Amy Sherman-Palladino’s Gilmore Girls is split into two Connecticuts. One is the city, a proverbial city that exists behind the gates of the privileged. We follow Rory Gilmore (Alexis Bledel) to her grandparents’ stately home, her prep school Chilton, and the ivy-clad bricks of Yale. It’s a world of affluence, deeply held grudges, and “downright Elizabethan” family drama.

But when the show makes its return on Netflix this week, what I’m most interested in seeing is the return to the other world: the quaint small town of Stars Hollow. It’s an absurd place, populated by the iconically fast-talkin’ townies who know each other by name. Town life in Stars Hollow is the seemingly comfortable static sitcom world within the show’s weekly melodrama.

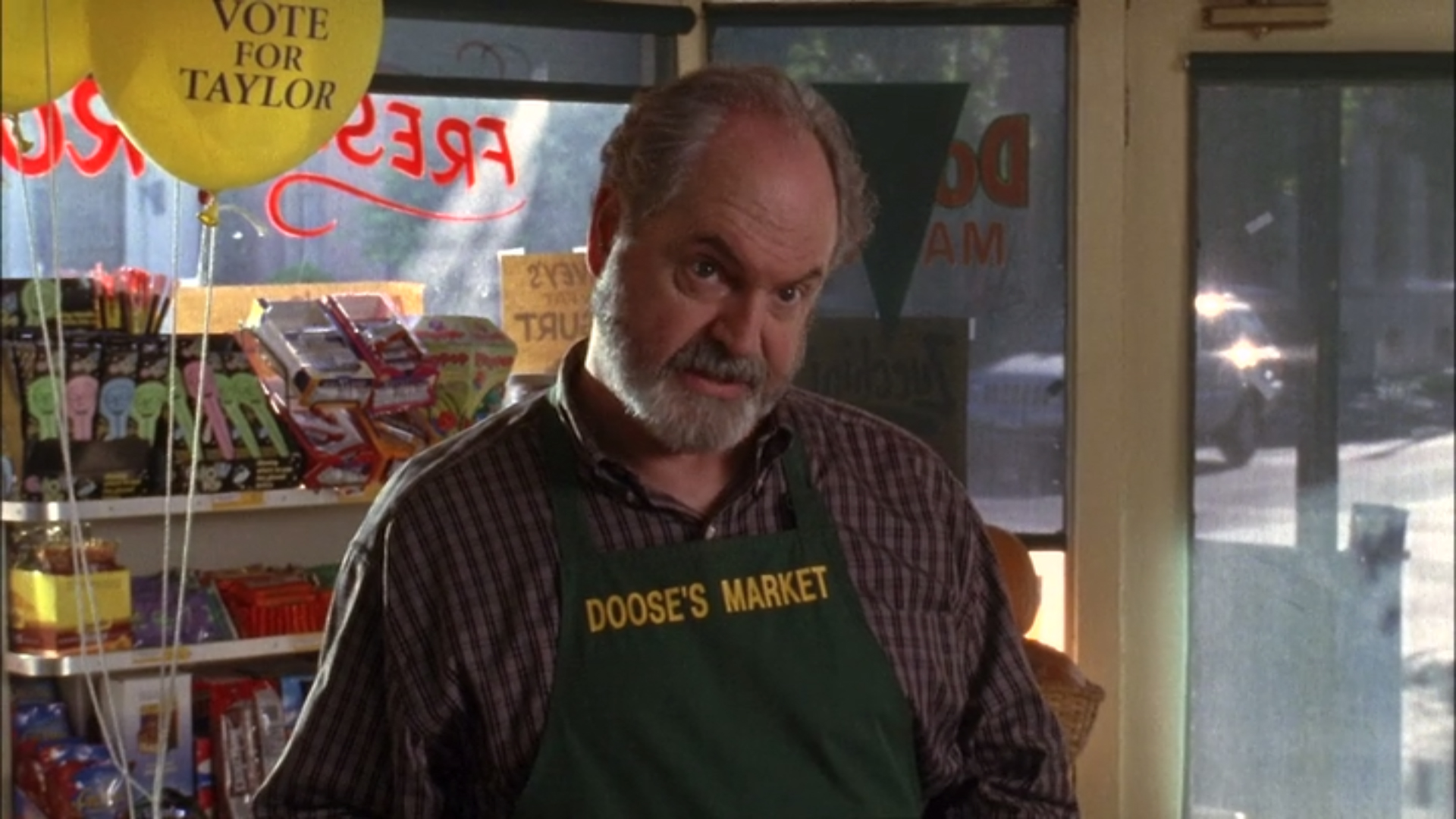

But beneath the kitschy charm is an insidious power dynamic, at the center of which is not the show’s protagonist Lorelai (Lauren Graham) or Rory, but the Town Selectman, a red-faced, conservative, evolution-denying salesman named Taylor Doose (Michael Winters). Doose is a conniving political opportunist whose appeals to fascism are sugarcoated with the candy he sells out of his grocery store and Olde Fashioned Soda Shoppe. He’s a man whose evil is played for comic relief by the Gilmores, who, though they are affected by his interferences, have their family’s wealth to fall back on—a privilege nearly nobody else in the town can tout.

[Mild Spoilers Below]

Taylor informs Luke precisely how short his grass will be

Taylor is a man whose community actions rely on upholding old traditions and trying to transform Stars Hollow into an amusement-park version of the Revolutionary Era—a place where the grass is always cut to an inch and a half. If he has a political platform to be sussed out, it’s Make Stars Hollow Great Again. Like any dictator (or political science undergrad), Taylor takes a page straight out of Niccolò Machiavelli: “Celebrate artists and promote festivals and parades,” as Machiavelli scholar Timothy Fuller puts it. “The leader should seek a balance between trying to satisfy citizens’ aspirations and being willing to utilize hard power.”

From the reenactments of the Revolutionary Battle of Stars Hollow (a battle that never happened) to the outrageously expensive hay-bale maze encompassing the entire town, there’s almost always some kind of festival going on. On the surface, these can be viewed as harmless celebrations, but make no mistake: Taylor still finds ways to enact petty vengeance through them. Without asking, he puts up posters of Rory’s face around town hailing her as the “Ice Cream Queen” to promote his Ice Cream and Soda Shoppe. Rory denies her royal calling, so Taylor shames her in front of the town as being “too good” for them.

The unveiling of the unwitting Ice Cream Queen

Taylor’s power in Stars Hollow isn’t limited to his political position. He’s a guy who would watch It’s A Wonderful Life and see Mr. Potter, the banker buying the town, as the hero, only crying because George Bailey’s wish of never being born doesn’t come true. When looking for a new apartment, Luke (Scott Patterson)—the cantankerous owner of the local diner—finds out that Taylor has purchased ten properties, is looking to buy the building next to the diner, and is “hopefully” getting the city council to enact a law forcing people to paint their buildings and install matching awnings. In response, Luke tells him he can’t control what colors people choose because “We don’t live in a fascist country.” To which Taylor retorts, “Oh this isn’t about the fascists—who, by the way, had their faults, but their parks were spotless.”

The Stars Hollow Gazette’s toothlessness doesn’t make it hard to imagine it as Taylor’s version of Pravda (or, for that matter, Breitbart).

The local newspaper, the Stars Hollow Gazette, is hardly mentioned aside from the occasional snide joke about not having having anything of importance to report on. Although Taylor’s actions and decisions as a leader should offer a well of material, not once is a reporter seen in a town meeting. In an early episode he decides that any movie in the video store that he deems inappropriate should be stored behind a giant red curtain and out of sight of the town’s children, which also has the effect of “[making] adults think twice” about checking them out. The Gazette is nowhere to be found, and it takes Paris Geller (Liza Weil), an outsider and editor of Rory’s high school newspaper, to actually confront him. The Gazette’s toothlessness doesn’t make it hard to imagine it as Taylor’s version of Pravda (or, for that matter, Breitbart).

The primary vessel Taylor uses is the strict coding and zoning laws. Taylor denies Lorelai’s request to add an additional parking space at her inn because she didn’t include her middle name on the form. A local farmer, Jackson Belleville (Jackson Douglas), works tirelessly building a greenhouse that Taylor orders to be destroyed because it’s nine and a half feet from the property line and not the stipulated ten. Taylor deflects all the blame to the bureaucracy of the town codes as if he isn’t the person who creates and upholds them.

The unveiling of the Rory Curtain

That is, of course, with the exception of when Taylor sees one of Luke’s buildings as the perfect location for his new soda shoppe. In a town meeting he threatens Luke with enacting eminent domain if he doesn’t rent the storefront to him, but it doesn’t end with a reluctant lease. While Luke is on vacation, Taylor has a window installed in the adjoining wall between Luke’s diner and this new store to complete his “turn-of-the-century” small town aesthetic goals. The two argue about Taylor breaking the lease, yet ultimately it’s never brought up again. Taylor keeps his store and the illegal window. While everyone must strictly adhere to every minute detail of his building codes, they can be conveniently forgotten for his benefit.

Small towns are often the subject of romanticism, their people revered as genuine and evergreen in comparison to a corrupt, elitist national political game. But Gilmore Girls asks why small towns would be any different. It’s easy to distance oneself from talking heads on television; we safely conclude their only interests are staying in power, because they have become characters to us—fictional characters juxtaposed with the sitcom that comes on right after the evening news. When someone’s tending to a farm or running a diner six days a week, paying close attention all the time is exhausting, and local litigation doesn’t entertain. Sci-fi author Douglas Adams once said, “Anyone who is capable of getting themselves made president should on no account be allowed to do the job.” True enough, but it’s always worth remembering that the person you see on TV started out as the bully next door. FL