Thomas Dolby broke out in the early 1980s with synth-pop hits like “She Blinded Me With Science” and “Hyperactive!” on the burgeoning MTV channel.

But that was only the start of his long career, one that has found him exploring the intersection of music and technology for decades. In addition to working with artists like George Clinton, Whodini, Eddie Van Halen, and Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead, Dolby became a Silicon Valley pioneer, founding companies like Beatnik and helping to establish a file type—the Rich Music Format—that allowed for dynamic sounds used by companies like Nokia. He parlayed all of that research into his current role as a professor of the arts at Johns Hopkins University.

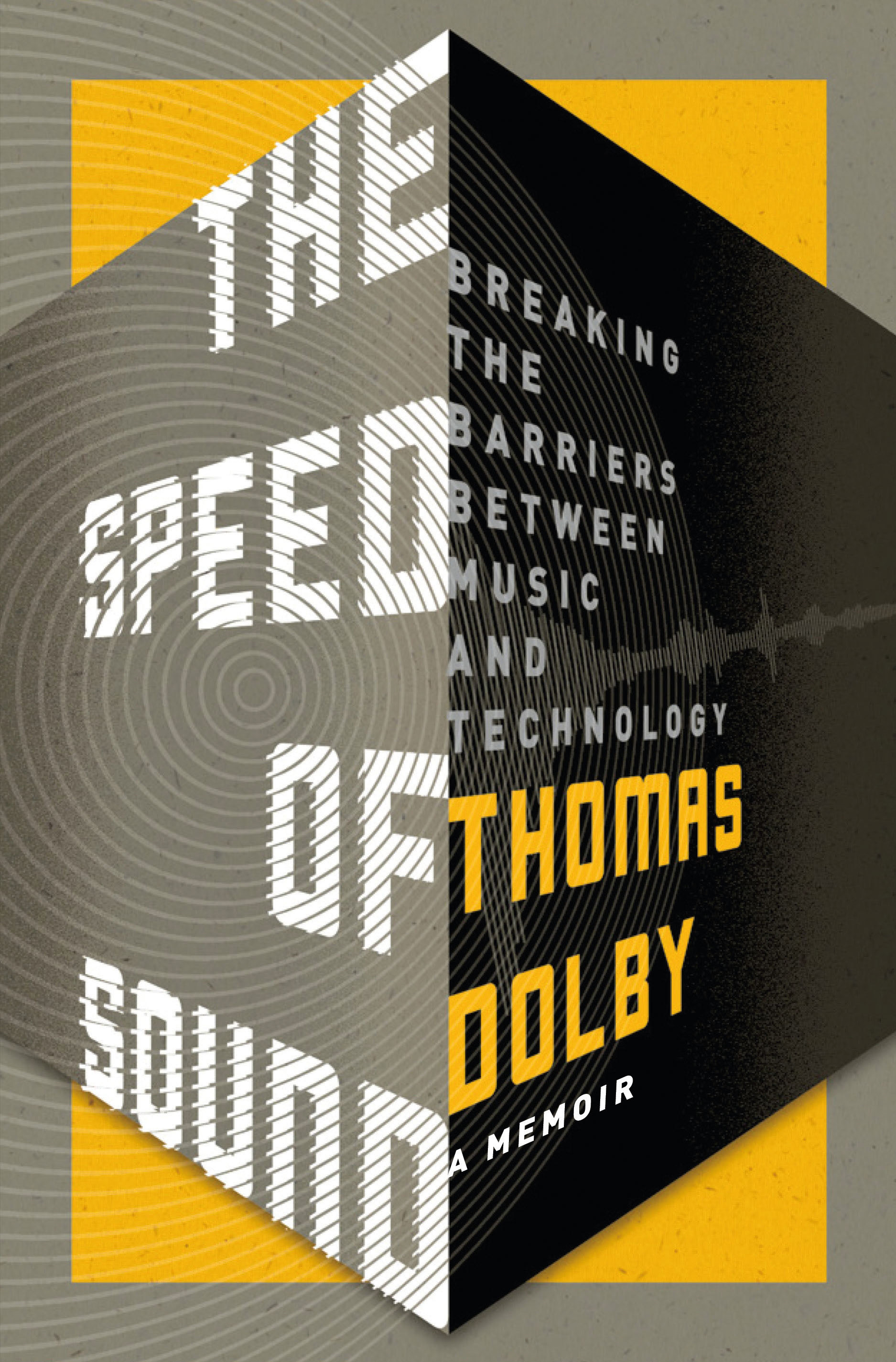

Dolby’s new biography, The Speed of Sound, opens with him singing potential collaborations to Michael Jackson over a pay phone and traces his rise from the English alternative underground to music video superstar to DotCom entrepreneur. Throughout, his matter-of-fact humor and quick wit add an easygoing lift to the narrative. Dolby is undeniably a groundbreaker, but he writes like a wisecracking everyman, the kind of guy who is as surprised as anyone would be when he winds up hanging out with David Bowie and giving a TED Talk.

Near the end of The Speed of Sound, you make a very interesting statement. You say you have “a fatal attraction to risky artistic endeavors.” Did writing a book feel like one of those to you?

[Laughs.] Well, I think it did, yeah. I’ve never written professionally before and I had no idea how people would take to it, whether they’d see it as an authentic voice or tell me I should have gotten a ghostwriter. But it seemed to go smoothly and the reception’s been really good so far. I think I get to stuff in the book that I don’t normally get to in interviews.

Why did now seem like the right time to write a book?

Since I’ve been teaching at Johns Hopkins, it’s put me in more of a reflective mood. I’ve been trying to figure out what I can pass on to my students that would be useful to them. The conditions of technology and the business landscape are going to be quite different by the time they leave university than it was when they were starting out, so there’s a limit to the amount of practical, contemporary advice I can give them. What I can hopefully rub off on them is a certain mindset and approach to creative problem solving. Very often, I didn’t stop to analyze why I did what I did and how I went about it. I’ve just blasted through it.

I was invited by a publisher to write a music/tech business book, and that didn’t really appeal to me, but it prompted me to go through some of my old journals and diaries, and what I found interesting is that when I wrote them, I had no context. I didn’t see the big picture. I was very much in the moment, and I thought that made quite a compelling read, as I was in some pretty extraordinary situations historically.

You came up in London as punk was breaking. You write about listening to the Sex Pistols, Elvis Costello, Siouxsie and the Banshees. Did you feel like punk rock offered you a format to express yourself?

Culturally, punk was great and fit what was going on with me at the time. I felt the sense of rebellion that existed, but musically, it didn’t do very much for me; punk bands didn’t really want a keyboard player. But there were other sub-movements going on, ranging from the art-school rock of Roxy Music and people like that through to the first germs of the electronic underground: bands like Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire and eventually The Human League.

That [was something] I found very stimulating and I was further buoyed by bands that had a new-wave energy but more elaborate musical progressions, like XTC and the Talking Heads. The end of the ’70s/beginning of the ’80s was a very fertile time for music. Although it took a while for that music to catch on commercially, I think with [the advent of] music videos there was an alternative way to promote it. You didn’t have to be dependent on radio playlists.

That [was something] I found very stimulating and I was further buoyed by bands that had a new-wave energy but more elaborate musical progressions, like XTC and the Talking Heads. The end of the ’70s/beginning of the ’80s was a very fertile time for music. Although it took a while for that music to catch on commercially, I think with [the advent of] music videos there was an alternative way to promote it. You didn’t have to be dependent on radio playlists.

MTV was pivotal to your success. At what point did you realize you were taking part in an emerging art form? Did it feel apparent at first?

I think it was quite apparent, yeah. The influence of MTV was very strong. If you had a successful video in rotation at MTV, the radio programmers were actually taking notice. It guaranteed you a certain amount of radio play [as] radio stations were switching over to formats that were comparable to the sequence MTV would run. That was a fairly new thing, and it broke down a lot of barriers. With conventional rock radio, there was a sense that synthesizers were wimpy and it wasn’t real music; it was cold and clinical. Drums and guitars ruled the day.

You write about “Hyperactive!,” a single from your fantastic second album, The Flat Earth, and about how the video got you in trouble with the label financially. Looking back, does that sort of complication feel like an inherent danger in being an early adopter?

I can’t really complain about that because [even though] a lot of things went wrong for “Hyperactive!,” things went right for “She Blinded Me with Science.” When you have a big hit, you don’t do a post-mortem on it. You don’t try and figure out what went right. You just go back and have a party.

And assume it will always work that way.

You assume that. And record companies tended to expect graphs to go up and to the right. “We did gold on the last one, let’s go for platinum on this.” But their marketing techniques were very unsound. They’d just throw money at a project and hope that it stuck.

It wasn’t very scientific, really, because music is not a product like soap or deodorant. It’s magic, really. When it catches hold, it’s very hard to analyze why it got into people’s psyches. The labels were mainly populated by music fans who couldn’t really believe their luck getting paid to do things they loved. They loved the rock and roll lifestyle, so I think as an industry, you can look back now and say it was a house of cards.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HHgNHneZ6WM

One of my favorite anecdotes is when you accidentally debunk your friend George Clinton’s UFO sighting. I think of George Clinton as a futurist—his work is driven by an attraction to the concept of the future. Did you view yourself as a musical futurist?

Yes and no. I’m not a futurist in the sense that I’m looking in a crystal ball trying to predict how things will go. I wasn’t interested in that. I was just very drawn to new forms of expression—whether it was a new technology or musical instruments—and outlets, like videos or the web or mobile phones. I got very excited by the possibilities and wanted to be among the first people to explore those possibilities and express myself in that new medium.

You ventured away from music into Silicon Valley, where you formed startups specializing in musical technology. Was there a similar creative drive that united your work in that field to your music?

There certainly was. There was the same kind of thrust to get into that that there was when I started working with synthesizers and computer music. In a way, the stakes were even higher. With the advent of the Internet, you had the ability to change people’s lives and society. That was really a thrill. It was a different industry. It was more adult, more sensible, but it got pretty silly, also, toward the end of the ’90s with the whole DotCom bubble. You saw speculative money pouring in, people trying to get rich—a gold rush, really. It got pretty irrational at that point, and I was swept along with it like a lot of people. I probably would have been swept out of the back end if it hadn’t been for, in a twist of fate, my company ending up getting its technology [picked up] by Nokia.

Did you ever envision music streaming on the level we currently have it?

Yeah, I think I envisioned music like a utility: you don’t stop and think every time you turn on the faucet how much that glass of water costs you. I always thought music consumption would end up being like that. You wouldn’t hesitate to check out a new band. When I was a teenager, you’d talk three months in advance about a new album that was due out and then go into the record shop and listen to it in a booth. You’d take it home and spend the next few days listening to side one, side two, over and over, poring over the lyrics. You’d talk with your friends and discuss it.

“You don’t stop and think every time you turn on the faucet how much that glass of water costs you. I always thought music consumption would end up being like that.”

Music was a much more precious commodity in those days. I’m not saying that was better, it was just different. Music listeners now are much more tolerant and have a wider range of taste. I think it’s a very healthy thing. I don’t think we should look down on it, because as far as breaking out, a musician can record an album on their laptop and distribute it via SoundCloud and get a worldwide audience overnight. It’s become a lot more of a meritocracy. In the old days it was difficult to get a record label’s attention and get signed and into the studio and onto the radio. Now it’s difficult because there are thousands of competitors for the same space. It’s progress and evolution.

You returned to music with your A Map of the Floating City project in the 2010s. What’s next?

I’m developing new programs at Johns Hopkins, which I really love. I’m not sure when I’m going to get back to music; I’m sure I will eventually, but what form that will take, I don’t know. FL