Carrie Fisher was my first love. Well—not Carrie Fisher, really. Princess Leia was my first love. For those of my generation, this is not a unique sentiment. As children we lived in the Star Wars universe, imagined ourselves as Lukes and Leias and Hans. We wrote sequels and prequels and standalone spinoffs long before Hollywood found a way to monetize our fantasy. And when Carrie Fisher passed away in the waning hours of 2016, a piece of our youth passed with her, and hearts once born anew to the very notion of love broke across universes both real and imagined.

I was born in September of 1976, so I was barely crawling when Star Wars debuted and changed the world. But I do have a very clear memory of, at four years old, being taken by my parents to the Bytowne Cinema in Ottawa to see a double bill of Star Wars and its seminal sequel The Empire Strikes Back. From that afternoon on, the Star Wars universe was my everything. I had no time for Luke Skywalker, however. I didn’t care much for his lightsaber or Jedi dogma. He was too much of a good boy. (And creepy in a way that was eventually explained by incest.) But Han Solo, the roguish anti-hero, captured and defined my youthful fantasies. Solo was who I wanted to be, and Princess Leia was who I wanted to… I’m not sure. I was in kindergarten. I had no understanding of love or desire or sexuality. But I knew that Leia was special.

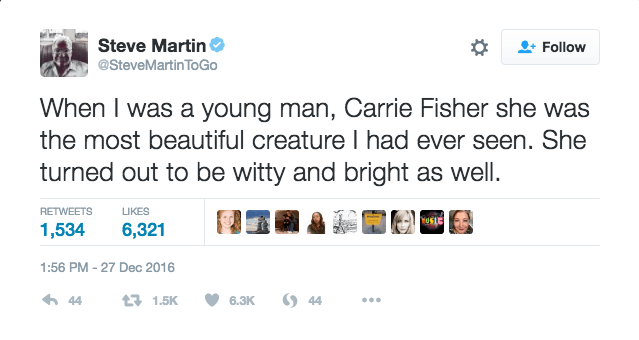

Steve Martin tweeted the following after Carrie Fisher’s passing:

Martin soon deleted the tweet, but was still rightfully condemned for it. He was using the Hollywood filter to quantify an actress whose defining role celebrated feminism and indulging in a simple understanding of the importance of Fisher and her princess. In her first moments on screen a generation fell in love with Leia’s wit and intelligence. The Star Wars saga begins with Leia confronting Darth Vader, the very embodiment of patriarchy, establishment, and evil. At four years old I had no idea who Carrie Fisher was. I had no grasp of the concept of actors. No clue that she was Hollywood royalty, the daughter of Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher. But I knew a badass when I saw one. And Princess Leia became everything I would come to understand and admire in women. She was strong, funny, fiercely independent, direct, fearless, and defined by purpose and not men. That was what made her beautiful.

Chuck Klosterman argued in his essay “This is Emo” from 2003’s Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs that his generation of heterosexual men were denied true love by John Cusack.

It appears that countless women born between the years of 1965 and 1978 are in love with John Cusack. I cannot fathom how he isn’t the number-one-box-office-star in America, because every straight girl I know would sell her soul to share a milkshake with that motherfucker. For upwardly mobile women in their twenties and thirties, John Cusack is the neo-Elvis. But here’s what none of these upwardly mobile women seem to realize: They don’t love John Cusack. They love Lloyd Dobler. When they see Mr. Cusack, they are still seeing the optimistic, charmingly loquacious teenager he played in Say Anything, a movie that came out more than a decade ago. […] This is why… the kind of woman I tend to find attractive will never be satisfied by me. We will both measure our relationship against the prospect of fake love.

I would argue, similarly, that my generation was not tainted by the fantasy of Leia, but rather encouraged to aspire to the love of women like her. Leia did not suffer fools. She was not a damsel in distress. She led a rebellion, she killed Jabba the Hutt. She offered a new hope.

For those who did not grow up in the ’70s and ’80s it’s difficult to explain how present the cultural phenomenon was. It wasn’t just part of the zeitgeist, it was the zeitgeist. We didn’t play cops and robbers; we played Star Wars. Posters adorned every bedroom wall. Millennium Falcons were torn open on Christmas mornings. Every Halloween was filled with Leias and Lukes and Hans. Nearly every young girl I knew, at some point, wore Leia’s buns and iconic white dress. We were immersed in the mythology. Leia wasn’t just on screen, she was in every young girl’s eyes, and every young boy’s dreams.

She was strong, funny, fiercely independent, direct, fearless, and defined by purpose and not men. That was what made her beautiful.

The reason that Leia’s ethos endures is not her sexuality or the crushes of prepubescent boys, but rather Carrie Fisher herself. Han Solo and Leia were the fantasies of a generation when they were new to the very concept of fantasy. But Harrison Ford went on to play Indiana Jones, Rick Deckard, and Jack Ryan, and to tell Gary Oldman to get off his plane. In other words, Ford became Ford, a Hollywood icon and not a singular character. But Fisher’s career took a different direction. Perhaps it was bad decisions—the abuse of drugs and alcohol she documented in her autobiographical novel Postcards from the Edge. Perhaps it was design, and Fisher understood that a lifetime of being Leia gave her, and the character, more power than any subsequent roles ever could. Her career saw her choosing to step away from the cultural prominence of Ford’s, and as a result, Leia stayed Leia. Her character remains static, the fourth wall never comes down, the fantasy remains. The Princess is allowed to inhabit our collective memory as Fisher portrayed her, with grace and wisdom and beauty, and not as an amalgam of Leia and Fisher herself.

With the 2015 release of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the story of Star Wars returned, and with it the series’ two original stars, one of whom had never left the front pages of tabloid culture and another who had spent a lifetime seeming to abandon it. When Leia first reappeared on the big screen, it was like walking into a high school reunion and spotting your first love from across the gymnasium. She was beautiful, and not simply through the naïveté of a purely sexual lens. She was beautiful in that she was the realization of years of imagination, of storylines that only existed in our collective fantasy.

As memories and tributes to Fisher flowed following her death, we learned more about the woman who had become, if not a recluse, then at least someone who didn’t crave center stage even though her career and pedigree afforded her that option. Fisher spent her life embodying that which Leia may have: she raised her daughter, Billie Lourd, without gender. She spoke out about addiction and depression and bipolarism. She worked as a script doctor, often bolstering female roles in male-dominated films. She fought the battles that so many in her position are unwilling or unable to.

She led the rebellion. FL