Azuma Makoto wanted to be a rock star. The Japanese artist was born in 1976 and moved to Tokyo when he was twenty-one to pursue his dream. When that didn’t pan out, he took on a gig as a trader at one of Japan’s biggest markets. In 1999, he became manager of a flower shop, then he opened his own shop, Jardins des Fleurs, along with a photographer friend.

It wasn’t until years later that he figured out how to connect the artistic calling that brought him to Tokyo to his day job. In 2005, he began to play around with experimental bouquets, unlocking the beauty, mystery, and strange potential of flowers (surely you’ve looked at one up close) by arranging them into botanical sculptures. Think of him as a deep-sea diver examining a coral reef, only he’s the one shaping the reef itself.

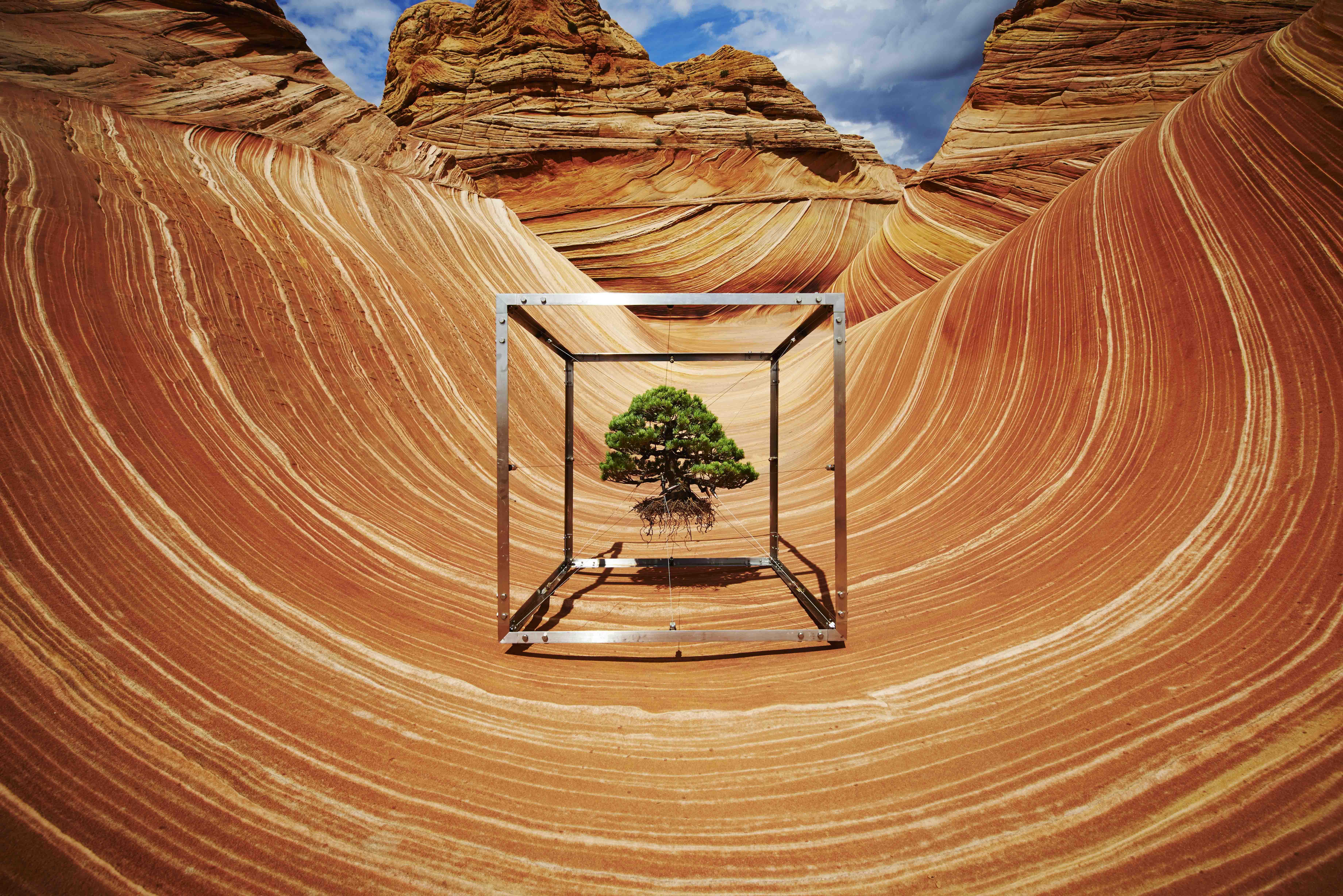

“I am always with flowers—confronted with flowers, thinking about flowers,” Makoto says. “This gave me inspiration, and I asked myself, ‘How I can turn them into new values?’” That desire to see his shop in a new way led to wild explorations. “I would take different approaches every time, such as capturing the crazily beautiful perspective of fresh flowers, or hanging flowers inside a cubic frame of stainless steel, or exploding flowers. And I would always search for the new way of expression by plants.”

“I am always with flowers—confronted with flowers, thinking about flowers,” Makoto says. “This gave me inspiration, and I asked myself, ‘How I can turn them into new values?’” That desire to see his shop in a new way led to wild explorations. “I would take different approaches every time, such as capturing the crazily beautiful perspective of fresh flowers, or hanging flowers inside a cubic frame of stainless steel, or exploding flowers. And I would always search for the new way of expression by plants.”

Makoto’s artistic career soon blossomed. He found himself running a private gallery in Tokyo and then founded an experimental nursery whose name translates to Azuma Makoto Botanical Research Institute.

“Working with flowers means working with life, living things,” he says. “In order to confront it, I need to be strict to myself. [For the location,] I chose the very center of Tokyo, where I always have to be energetic and behave like a fighter.”

As the institute grew in popularity, Makoto’s work became more in demand, and he participated in dozens of exhibitions, installations, and performances—mostly in Tokyo, but also in Paris, Milan, and (of all places) Dallas.

As the institute grew in popularity, Makoto’s work became more in demand, and he participated in dozens of exhibitions, installations, and performances—mostly in Tokyo, but also in Paris, Milan, and (of all places) Dallas.

Around this time, he hooked up with the Atlanta band Algiers, whose vicious take on post-punk saw wide release on their 2015 self-titled debut. Makoto had caught wind of their so-called “dystopian soul” tunes—unique in their own right—while the band had discovered him through “Exobiotanica,” a project in which he launched plants into the air with the aid of aerospace engineers.

“We also share an interest in strange, out-of-the-way buildings and spaces, having both worked inside Bulgaria’s abandoned mountaintop Buzludzha monument in the past couple of years,” says Algiers guitarist Lee Tesche.

“We also share an interest in strange, out-of-the-way buildings and spaces, having both worked inside Bulgaria’s abandoned mountaintop Buzludzha monument in the past couple of years,” says Algiers guitarist Lee Tesche.

It was actually Makoto who reached out to Algiers, and the artists’ schedules kismet-ically aligned so that they could collaborate for special videos for the Algiers songs “Blood” and “Black Eunuch”—songs that Makoto says resonated with him philosophically and emotionally. “I collaborate with artists or musicians who play emotional sounds as if they’re bringing new plants to life,” he says. The band was in California for Coachella, but it was Makoto and his team who came up with the palm-tree concept and handled all the logistics, according to Tesche. They involved figuring out how to suspend a giant palm tree above the band while they played in a remote slab of desert.

“When we got out there, we were so blown away by the setting and how cool Azuma was that we just set up and played every song that we knew around the tree for him, including some new songs,” the guitarist says. “The tree was this giant monolithic form in the middle of this endless dry lake,” Tesche recalls. “It was hard not to just stand there in awe of the whole thing.”

He adds: “The environment there was so unforgiving and insane. The acoustics and sound there were really unlike anything that I had encountered before. It was really hard to describe, really haunting. I remember at one point [singer/guitarist] Franklin [James Fisher] showed me how the bursts of wind were affecting the guitars and we both held our guitars aloft and let them howl and moan in ways that I haven’t been able to recreate since.”

While Algiers and Makoto hope to reconnect in Japan and collaborate again, the artist is off to his own endeavors. He’s planning a project in which flowers will be sunk in the deep sea—a sister piece to “Exobiotanica”—to be launched sometime this year.

Still, he’s able to wrench complex and powerful emotions from the smallest of exhibitions. Last summer, he staged a one-day installation with the self-explanatory title “Burning Flowers” in memory of a friend who recently passed away. “Flowers being burned with the crackle were so beautiful,” he says. “It gave me the idea of new botanical possibilities.” FL

Still, he’s able to wrench complex and powerful emotions from the smallest of exhibitions. Last summer, he staged a one-day installation with the self-explanatory title “Burning Flowers” in memory of a friend who recently passed away. “Flowers being burned with the crackle were so beautiful,” he says. “It gave me the idea of new botanical possibilities.” FL