Hari Kunzru’s new novel White Tears begins, simply enough, as a story of two white dudes chasing after the “realness” of black music. Hunkered down in their New York studio, the producers know how to make bands sound “authentic.” They’re in demand by garage bands and rappers, keepers of analog purity and warmth. You know the types.

They come from two different worlds. Seth, the novel’s narrator, is obsessed with sound and comes from meager means; Carter is tapped into old money, able to access a seemingly endless flow of capital as he moves from an obsession with dub and reggae to collecting pre-war blues 78s. But the duo is united by what they feel is their right to possess black music. “Appropriation” isn’t the word, in their minds—they believe themselves stewards of it. Again, you know the types.

But things take an arcane turn when Seth captures the airy strains of a blues song in Washington Square Park while out on a field-recording expedition. When he listens back later, he can’t remember the performer, and is almost certain he didn’t see one, but there’s a haunting quality to the song:

But things take an arcane turn when Seth captures the airy strains of a blues song in Washington Square Park while out on a field-recording expedition. When he listens back later, he can’t remember the performer, and is almost certain he didn’t see one, but there’s a haunting quality to the song:

“Believe I buy me a graveyard of my own / Put my enemies all down in the ground.”

Seth and Carter mix the vocals, adding static and crackly guitar, approximating decades and decades of surface noise. “Make it dirty,” Carter commands. “Drown it in hiss. I want it to sound like a record that’s been sitting under someone’s porch for fifty years.” They fashion it into a lost 78, which Carter “digitizes” and uploads—counterfeit label and all.

Strange things begin to happen. A grubby stranger from the Internet gets in touch, demanding to see the record, which he claims to have heard in 1959. Slowly, reality begins to blur, taking on a horrific edge. Carter and Seth’s forgery becomes—or always was?—real, and the concerns of race and appropriation, of the unpaid debts to the enslaved black people our country’s never paid back, bloom from existential and cultural questions into bloody ones.

Kunzru gleefully morphs his ghost story into a frightening, maddening exploration of the literary horror genre. His use of language is sharp, and his lightning-fast prose makes for a delirious read. His ghost—an old bluesman named Charlie Shaw—is a spirit of vengeance, a ghastly reminder of the injustices our country was founded upon. He’s a specter of the cost—in human flesh and blood—of that “great” America our president talks about at rallies and in speeches.

But Kunzru’s a careful guide into this world. He’s not sanctimonious about any of this. He’s no stranger to the allure of the blues, and coded throughout the book is the idea that art can reveal shared humanity and experience, if the listener is willing to know the singer as well as the song. It gets messy and confusing. But Kunzru isn’t after clarity necessarily; he’s drawn to the ambiguity of what constitutes authenticity, and he revels in the complications that humans bring to their art, and those we bring to the table when we listen to it.

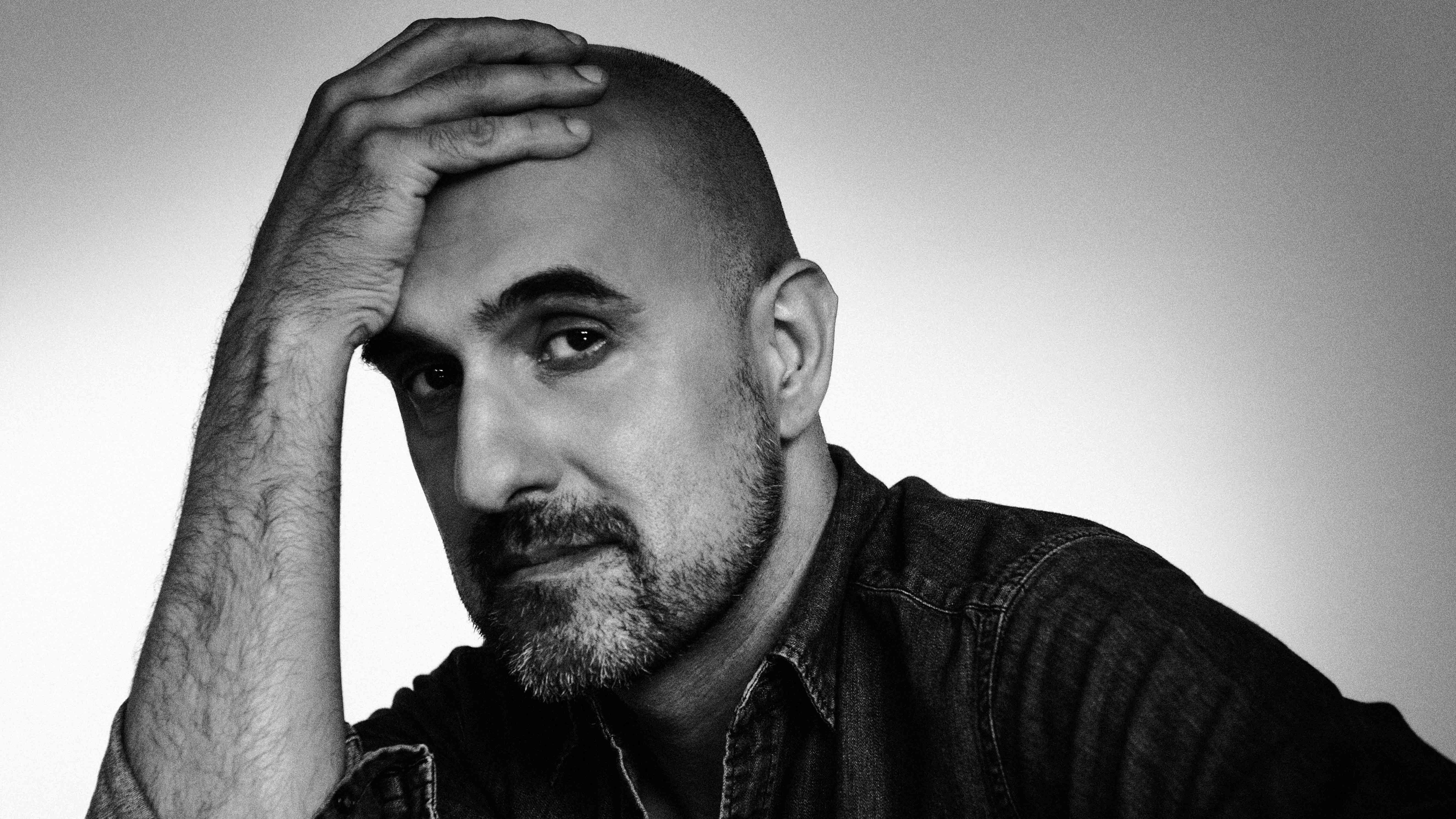

You set out to write a genre book with White Tears, but did you expect to write a “horror” novel at all? Does that description sit with you well?

I think of it as more of a ghost story, really, rather than horror, although the two things are obviously intertwined. My logic was that ghost stories are always about something that’s been repressed, a memory that has been prematurely cast into the past and somehow finds its way back into the present to haunt people. It’s often to do with an unresolved guilt. Think about how many American horror stories have their setting in something that turns out to be an old Indian burial ground, you know?

I’ve been living in the US for nine years, and one of the things I’ve found most disorienting is how unresolved the whole question of race is here, especially the history of African Americans. I had my own history with race stuff, obviously, coming from Britain, having that whole imperial story and some set of relationship to these questions, but it struck me that America is a country haunted by race, and a ghost story would be quite a good way of trying to talk about that and how it informs the present. Quite separately, I’d just for pleasure started listening to 1920s and ’30s music and got more and more drawn into it. And the two things really became meshed together.

In the book, these collectors are all drawn to this music, and in some ways they share that spirit with folklorists like John and Alan Lomax and Harry Smith and Chris King. But we’re kind of made to understand the sinister side of collecting as well. How difficult was it to you to parse out the complicated motives of collectors? What fuels that record lust?

I’m always drawn to ambiguity of this kind. You need to acknowledge that the collectors did amazing cultural work, and that without them—not just the Lomaxes, but the New York–based collectors, they called them the “Blues Mafia,” these guys in the late ’40s, early ’50s—they did rescue a lot of this music from oblivion. But at the same time, their taste kind of warped the way people understood the music. Without the legend of Robert Johnson [that they engendered], you don’t get all those ’60s rock stars; you don’t get Jimmy Page, you don’t get Keith Richards—and you also don’t get that really queasy folk-revival stuff where the old guys are dug up out of wherever they’ve been for the last fifty years and lots of fresh-faced young white teens try to get a hit of authenticity.

“Nobody is getting freed by you sitting there with headphones on listening to A Love Supreme.”

As a kid, I was exposed to a lot of black American music; it was a very weird wrinkle in the white suburb where I lived in London. There was a big jazz-funk scene, with a lot of these hard, quite racist white guys listening to Donald Byrd records, which is a strange case. My understanding of African American culture has [come] through music, but also, I don’t own this stuff. That was quite educational for me as I gradually realized the oddness of my listening to some ’70s jazz record.

I think it’s tempting to imagine that if you heard a Donald Byrd record, or Gil Scott-Heron, or Sun Ra, and you appreciated that, it would somehow magically transcend your personal context and history. It’s such a common claim: How can I be racist if I have such an appreciation for this beautiful thing?

There are plenty of [people]—especially young men—who hope in exactly that way. “I have a fantastic collection of Sun Ra or Pharoah Sanders [or] whatever it is, therefore that’s my get-out-of-jail-free card for structural stuff I’m not paying attention to or taking into account.” Nobody is getting freed by you sitting there with headphones on listening to A Love Supreme. What I wanted to do in the book was tie contemporary northern hipster culture here in New York back down to those old stories about racism that people very often say has something to do with the South, or something to do with history, [as if] it’s all over and done.

I arrived in the States in time for the 2008 election campaign, and it was very noticeable how quick a lot of people were to hope for a post-racial America. “OK, we elected a black president, it’s done now. We don’t have to think about redlining, we don’t have to think about any of the stuff that went on back then, because surely this is a demonstration that it’s all over.” And of course, we’ve seen that anything but that happened. I think one thing I wanted to say with the book is that a person could have an impeccable collection of ’70s soul records and still be part of the problem.

That’s an uncomfortable truth the book grapples with. But one of the things I appreciate about it is that it’s ultimately not only about the blues or simply artistic cultural appropriation—it’s about the real, tangible transactions between black and white in this country. It’s about the powerful exploiting the powerless, and a lack of payment, recognition, and compensation for the work provided. It’s timely in a truly upsetting manner. Is this book in some ways a reminder what the “great America” actually looked like?

I think Trump’s great America involves a lot of labor camps and people working for free. It involves a return to hierarchies that we desperately need to transcend; it should come as no surprise that his idea of greatness is not mine. It was all written well before the election, but most of it was written within the post-Ferguson atmosphere in the States, when it became clear that these structural things were still in play. I think there’s a great tendency, especially among the white right in this country, to say Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and we’re all good, so why are you still whining?

The character JumpJim delivers one of the most stinging quotes in the book when he says “there ain’t no real, it’s just people.” I think that’s what that search for authenticity glosses over: the complicated humanity of everyone involved. That’s one of the things the book grapples with in a way that struck me—that these are complicated characters with complicated motives. Even the ghost is complicated.

Authenticity’s long been a preoccupation of mine, partly because of my own racial background. My father’s Indian, and my mom’s English. The context in which I was brought up, I was never white enough and I was never brown enough. That kind of inability to completely fulfill roles or be at the center of anything was always a real driver for me to do something as dumb as writing books rather than something sensible and productive. [Laughs.]

“One thing I wanted to say with the book is that a person could have an impeccable collection of ’70s soul records and still be part of the problem.”

You look back to what the white hipsters wanted from the blues, which was kind of a politically inflected, heroic authenticity. And what Lomax wanted—John Lomax—was untouched authenticity. He wanted Lead Belly [as] a genuine murderer who had to perform in his prison stripes for elitist parties on the Upper West Side. So, all along, the bluesman gets made into this primitive, this rather immobile figure of purity and authenticity. When you get to know the music, you realize it’s so much more complicated than that. People had these commercial careers where they were playing a repertoire of music hall songs, Irish jigs, all sorts of different things. Many of these guys were professional entertainers, working in medicine shows, people who had sophisticated and complicated ways of presenting themselves. For every sharecropper who sits on his porch and plays his guitar, there’s another guy who’s a conscious professional.

The narrator, Seth, keeps saying, “This is my story too.” If you’re going to claim the blues is your story, too—and I say this as a white dude—you have to be willing to unpack all of it, not just the part that you like to hear. I think in a way, that’s what the book asks you to do. It asks you to untangle the threads that connect the privileged elite to the free labor that the country was built on, and face those connections in their ugliness and horror.

There’s a great white wish for innocence in this country—such a strong desire to feel pure and orient yourself toward the future and not worry too much about what went on back then. That’s very toxic. I think there’s a certain distinction you can make between love and ownership. I think you can love something without trying to own it.

That’s true and necessary to remember.

Acknowledging your full context, in relation to any kind of art—but especially art that’s as full as this—is important. And I don’t think it necessarily lessens your pleasure or the intensity of your relationship to it. If anything, I think it increases it. FL