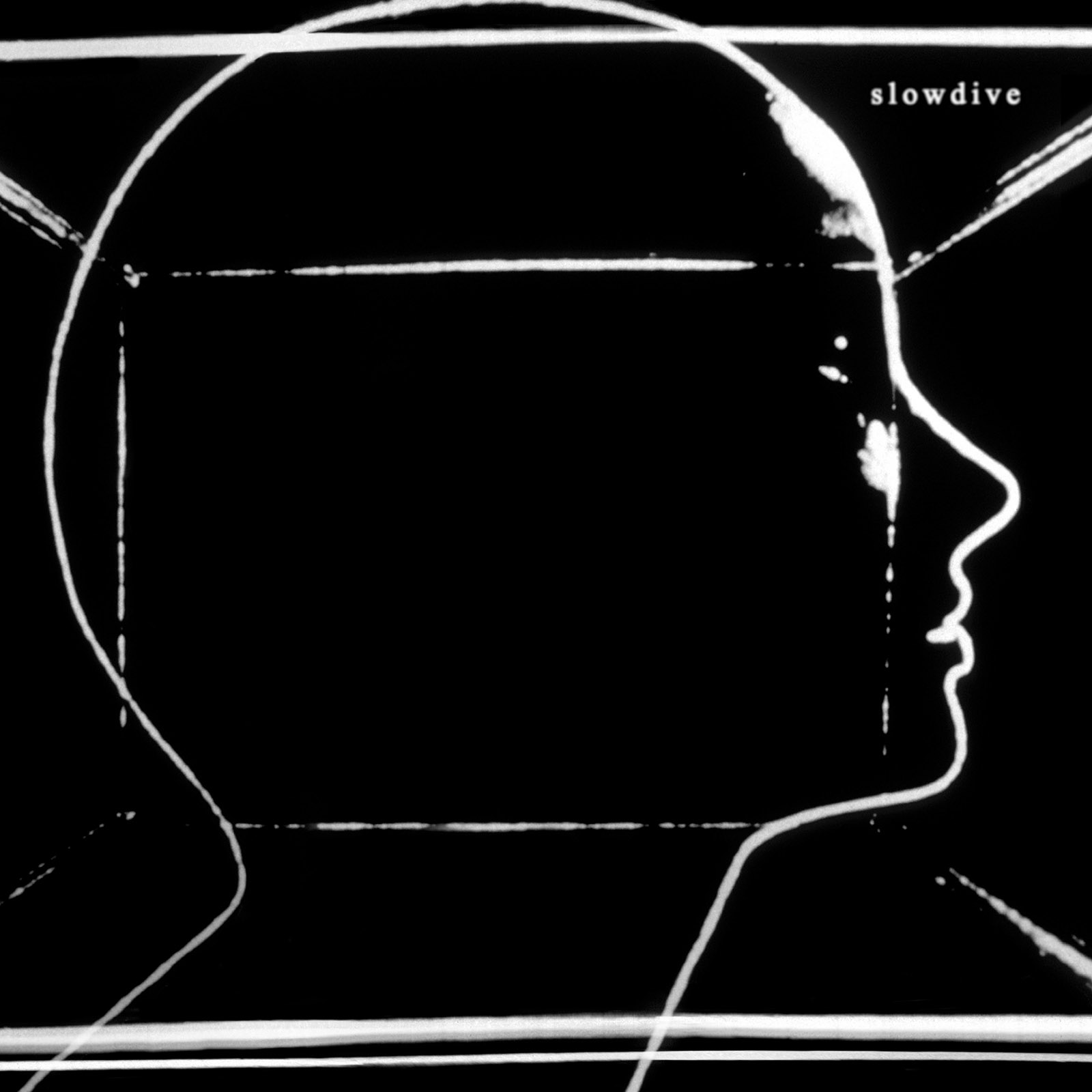

Slowdive

Slowdive

DEAD OCEANS

8/10

For all its celestial aspirations, time has revealed something significantly more pragmatic about shoegaze: It doesn’t really age. Indeed, like surrealist art, which has its trade in the artistic representation of the subconscious, the otherworldliness of all those thrice-flanged guitars places the vaporous genre far above such niggling earthbound nonsense as cultural and social zeitgeist. Blur’s Parklife sounds like a product of its era; My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless sounds like the ninety-nevereth-of-ever.

But despite MBV’s having gotten there first, their penchant for sonic brutality ultimately overwhelmed their aesthetic. Slowdive’s beatific debut, Just for a Day, came three years after Isn’t Anything, but it suggested the possibility of shoegaze in its most sublime, perfected form. The exquisite, almost unimaginable Souvlaki, which was released in 1993, made that a reality. To be sure, Slowdive are still the model to which all ‘gazing must be held.

Gloriously, on their first album in twenty-two years, they don’t even try to not be Slowdive. The very first notes of opener “Slomo” fade in from some far-off galaxy before Neil Halstead intones incomprehensibly, as if singing through a thick, romantic fog. “Star Roving,” which follows, may be the most exuberant piece of music they’ve ever composed, proving once more that, despite its introverted nature, shoegaze possesses the possibility for truly anthemic gestures; the august, widescreen “Don’t Know Why,” with its machine-gun drumming and towering wall of echo-drenched guitars, only confirms it.

If there’s anything resembling a misstep, it’s the closing “Falling Ashes,” a fragile little piano ballad far more suited to Ryuichi Sakamoto, which doesn’t totally belong in its surroundings. But for the first thirty-eight minutes, everything is saturated in echo, the guitars have more layers than a mille-feuille, the snare is tinny, and nothing is unfamiliar. Yet the intensity and zeal that drives virtually every note through the mist and on up to the very heavens feels wondrously urgent—and utterly imperative as ever.