Buying, playing, and discussing records was an integral part of the making of the Beastie Boys’ third album. Here are twelve slabs of wax that were in constant rotation at G-Son.

Listen along via Apple Music below.

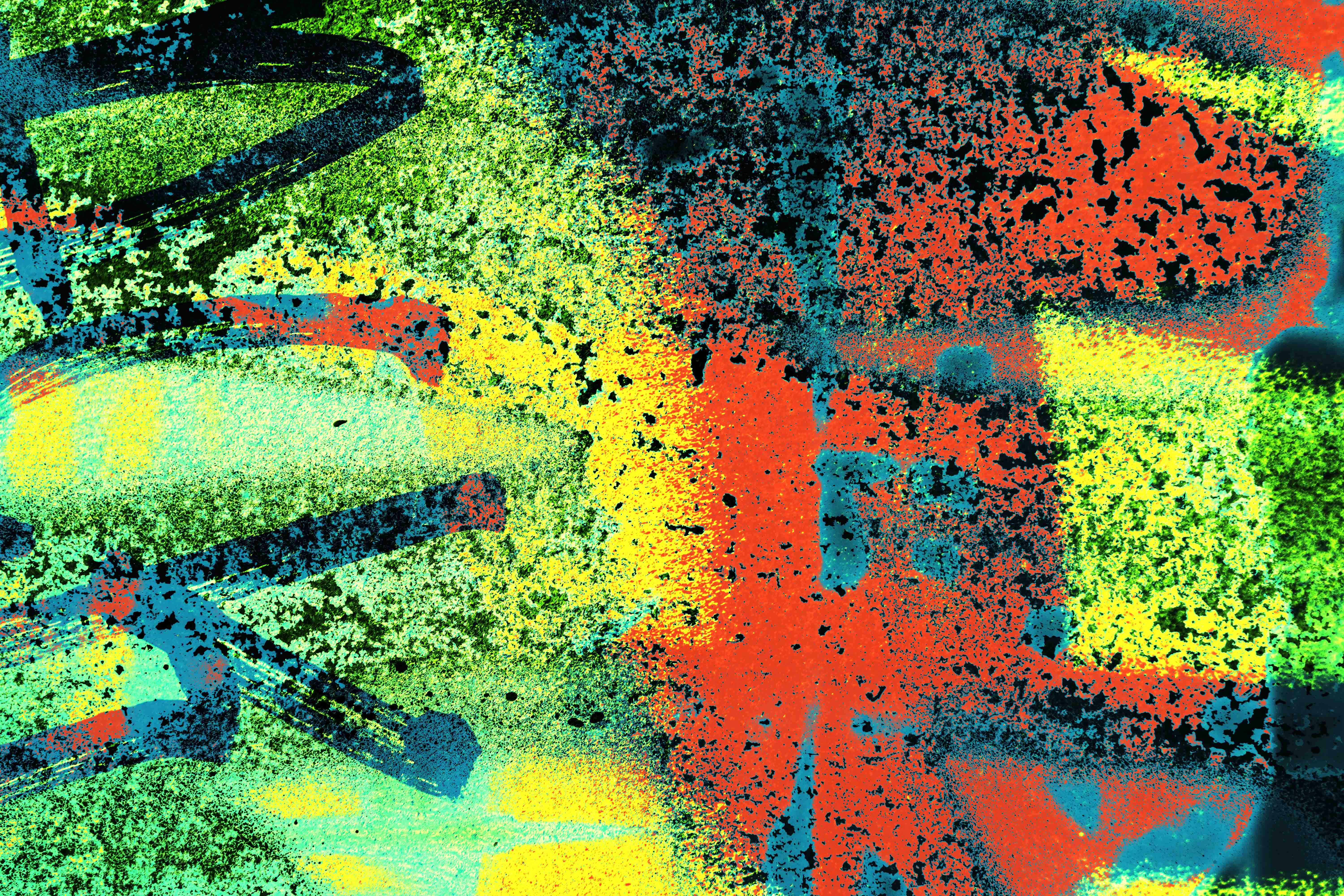

Alice Coltrane — Journey in Satchidananda

While Adam Yauch’s trip to Nepal instigated his lifelong relationship with Buddhism, it wasn’t the only thing influencing the mental direction of the three Beasties. Alice Coltrane’s 1971 classic of spiritual jazz still sounds mind-expanding—has anyone else ever managed to make a harp sound jazzy?—and the album’s effortless intermixing of tablas, sitars, stand-up bass, and brushed drums suggests a search for transcendence both musical and spiritual.

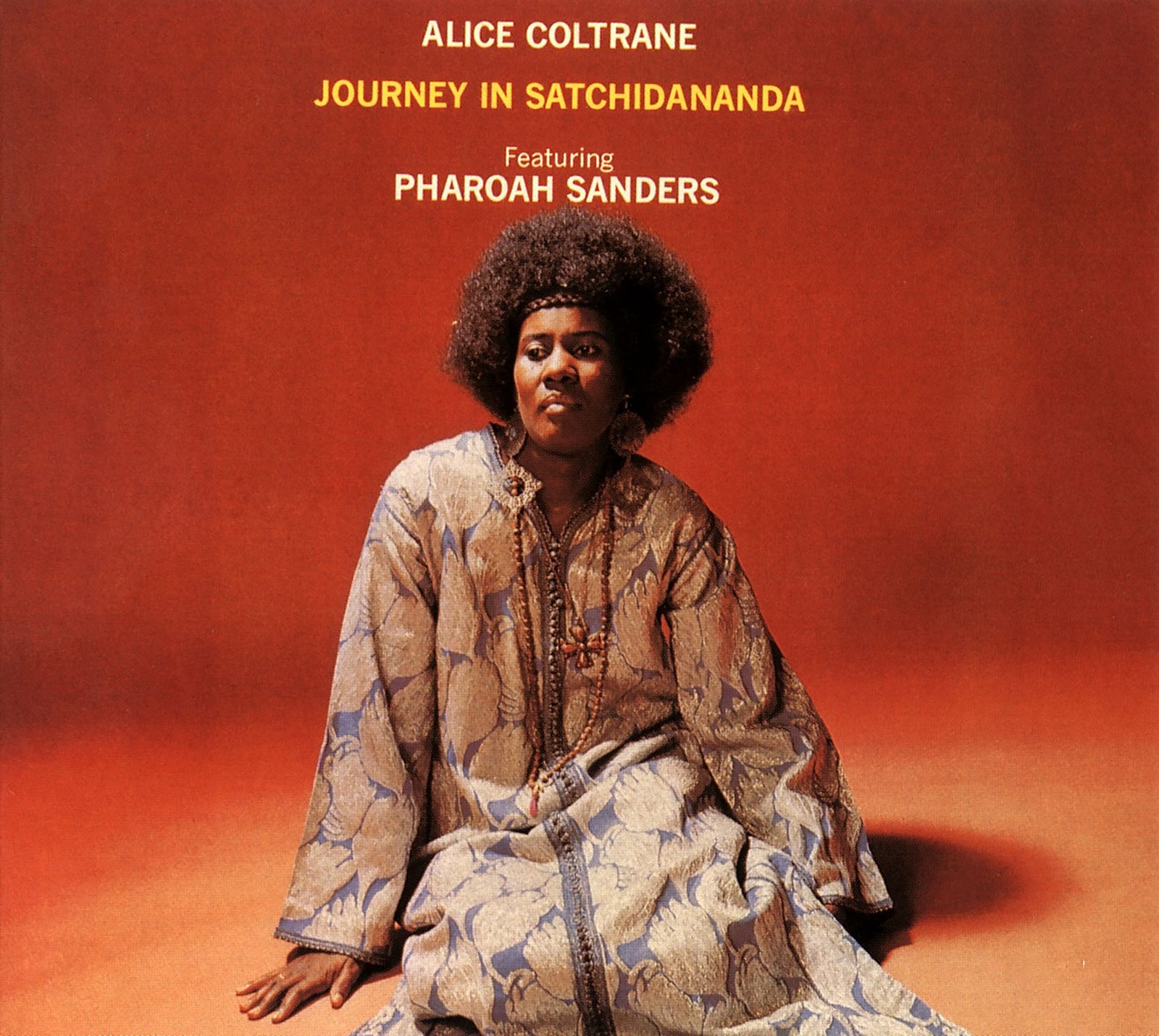

John Coltrane — A Love Supreme

“Sure,” you’re thinking, “Every band ever cites A Love Supreme as an influence, when we all know they were listening to Thin Lizzy.” But in the case of the Beasties, the Coltrane classic actually was in heavy rotation. (And before you speak ill

of Thin Lizzy, play “Funky Boss” next to “Showdown.”) While the album provided them with the same spiritual nourishment they were getting from Journey in Satchidananda, there’s a cool, slightly sublimated tone to the John Coltrane classic—this is questing music, for sure, but we never get the sense that the saxophonist is losing himself in the process.

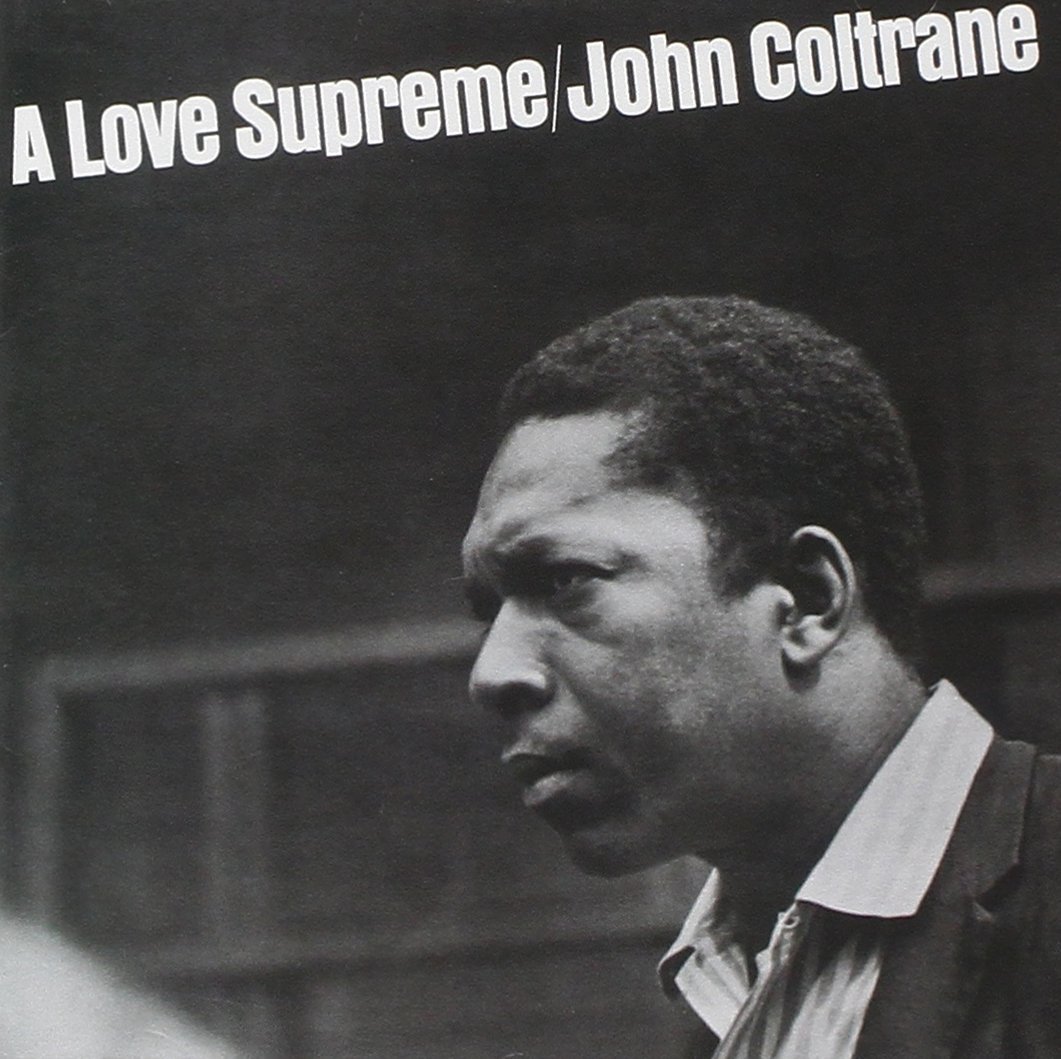

Kool & the Gang — Live at P.J.’s

It’s exceedingly difficult to believe that Kool & the Gang ever made music for any purpose other than having it played on cruise ships, but before they were celebrating good times, they were an outrageously funky combo playing small clubs around the US. Live at P.J.’s was recorded in West Hollywood, a mile or so from Ad-Rock’s Check Your Head–era apartment, and it captures the band barreling through hard funk (“Ronnie’s Groove”), strutting soul (“N.T.”), and pensive jazz pocked with the bright horns that would eventually turn them into hitmakers (“Dujii”).

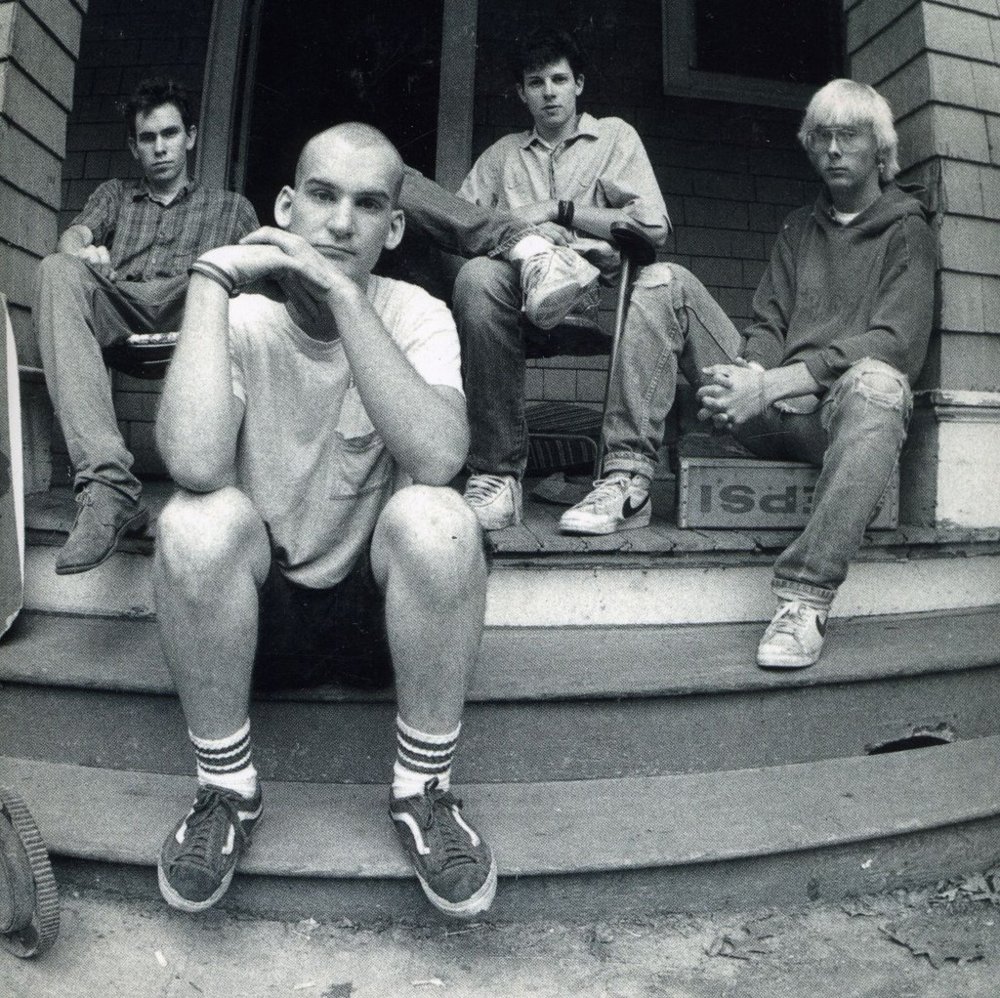

Minor Threat — Salad Days EP

Even leaving aside the Beasties’ return to hardcore, the influence of Minor Threat’s final release on Check Your Head is indelible. Over a for-them-sprawling two minutes and forty-six seconds, the DC hardcore legends abandon genre orthodoxy on the title track in favor of experimentalism: Acoustic guitars! Chimes! Spoken, obscured vocals! Such creative independence would define Check Your Head; during the photoshoot that eventually yielded the album’s cover, Yauch even asked photographer Glen E. Friedman to make them look like Minor Threat on the cover of the Salad Days sleeve.

A Tribe Called Quest — The Low End Theory

With a few splashy exceptions—a wash of sax, a chickenscratch guitar, a sampled backbeat—there are three sounds on The Low End Theory: live drums, stand-up bass, and voice. In the case of “Verses from the Abstract,” that bass comes courtesy of legendary sideman Ron Carter, whose work on Johnny Hammond’s “Big Sur Suite” is sampled in “Pass the Mic.”

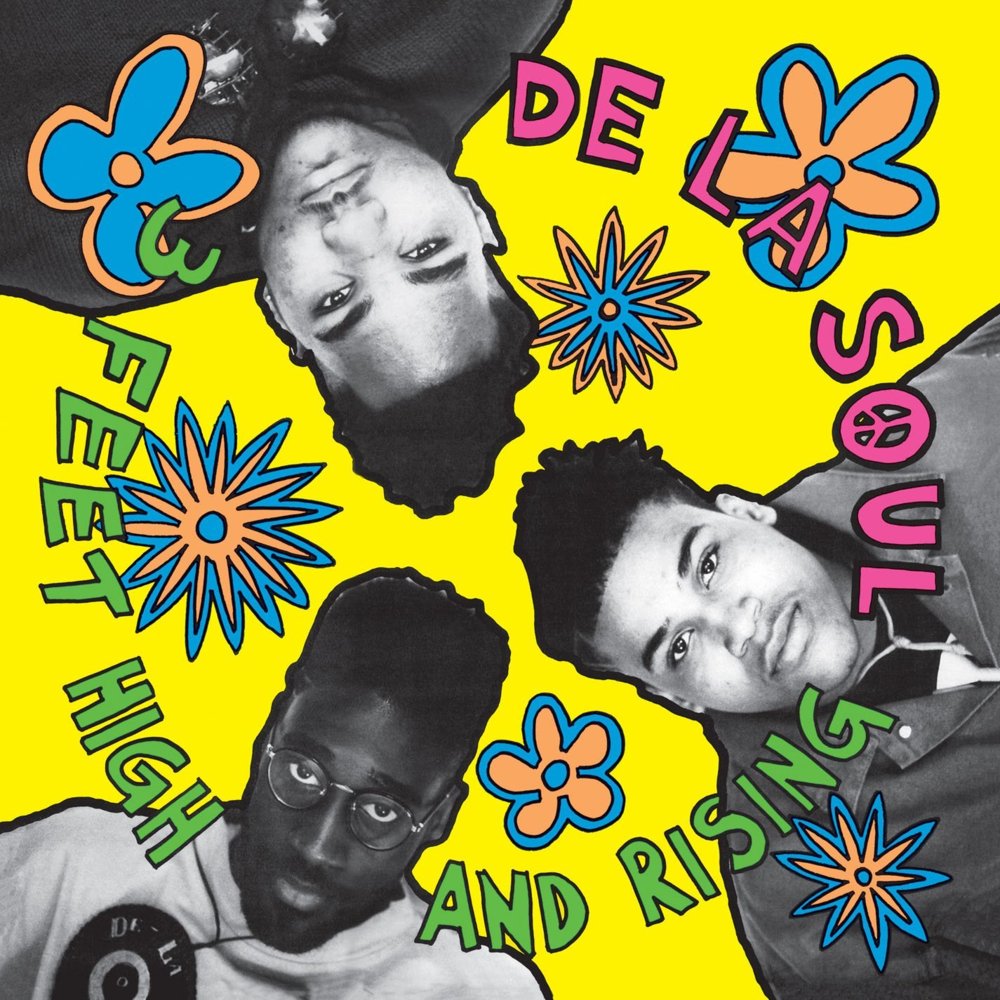

De La Soul — 3 Feet High and Rising

3 Feet High and Rising is a stone-cold classic, and it’s an unspoken influence on just about every hip-hop record to come in its wake. The album’s wiggy psychedelia, Steely Dan samples, and weirdo interludes were enough to put the Beasties off their game while they were wrapping Paul’s Boutique, but it also gave them the confidence to pack Check Your Head with odd interstitial moments like “Mark on the Bus.”

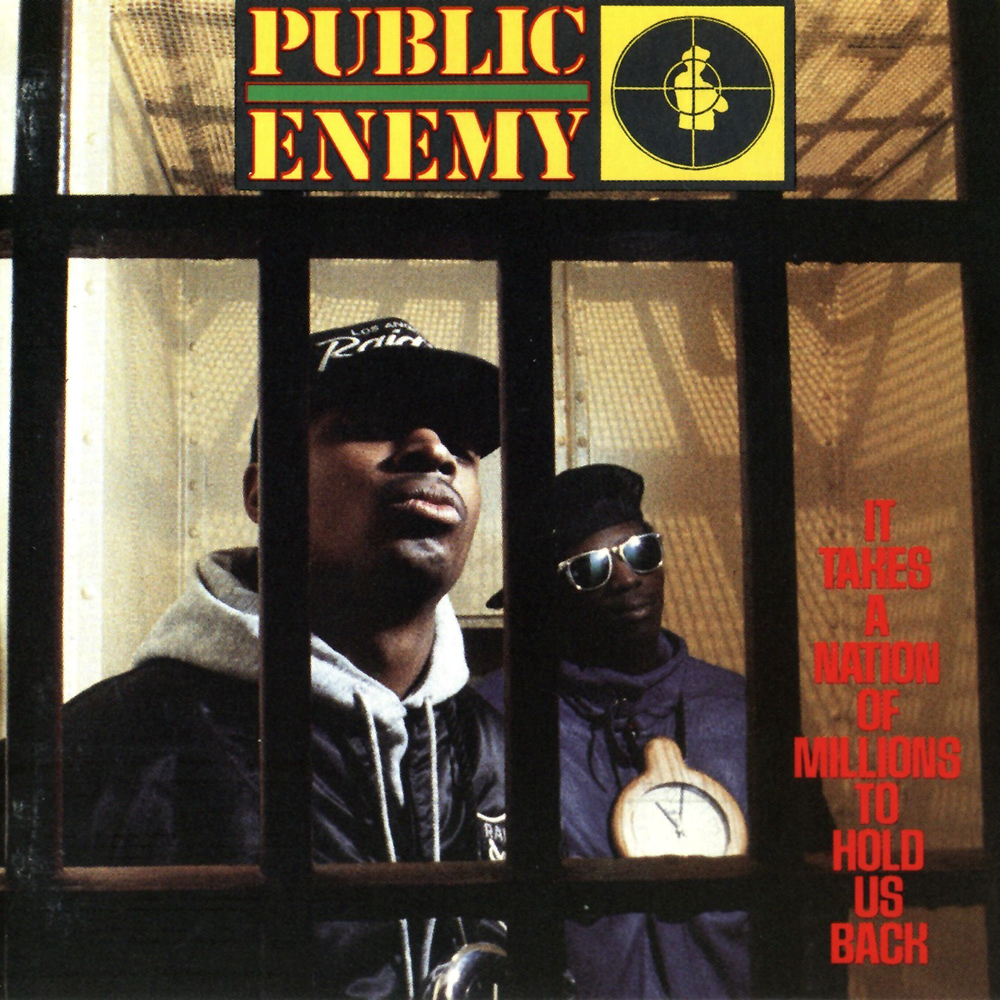

Public Enemy — It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back

As the ’80s begat the ’90s, was there anyone in hip-hop who wasn’t taking notes from Public Enemy? Yes, Chuck D (no relation to Mike) raps with a fury and conviction that still makes him impossible to argue with, but It Takes a Nation is also a remarkably funny record—all those “Yeahhh, boy-eee”s aren’t in there for Flavor Flav’s health—and it’s a feat of engineering, too; the motion-blurred spinning of Queen, The J.B.’s, and Big Audio Dynamite in “Terminator X to the Edge of Panic” is still dizzying.

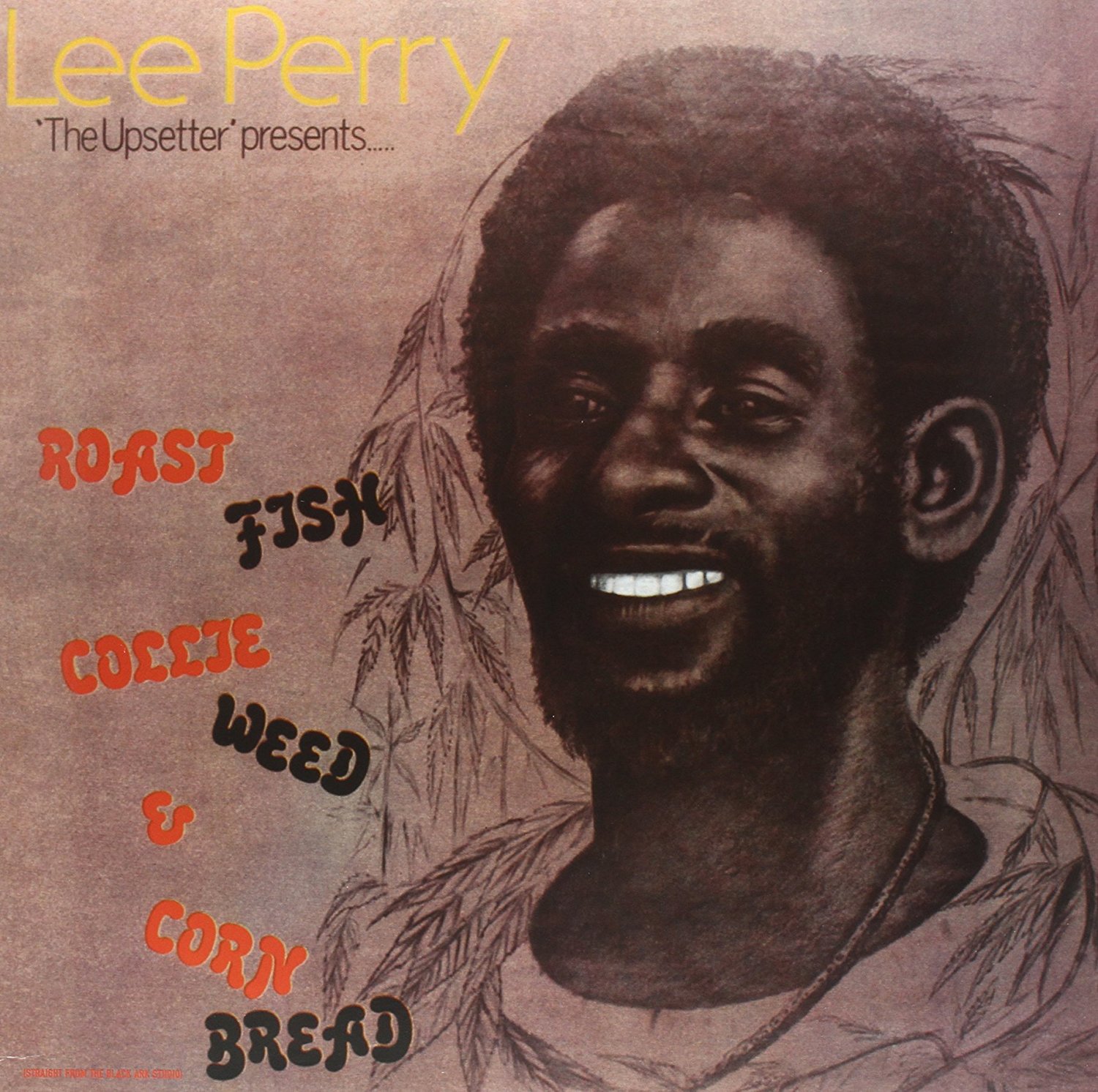

Lee “Scratch” Perry — Roast Fish, Collie Weed & Corn Bread

A Lee “Scratch” Perry production never feels like it should work: minor percussive sounds might sit right in the front of the mix while the vocals sound like they’re being recorded in the next door neighbor’s bathroom. Whole songs might be drowned in so much reverb and spangled with so many whirrs and ticks that it can take four or five listens before their actual formal complexity begins to come into view. In other words, Perry is able to synthesize disparate sounds by force of his own quirks and personality—a concept that is the essential guiding force of Check Your Head.

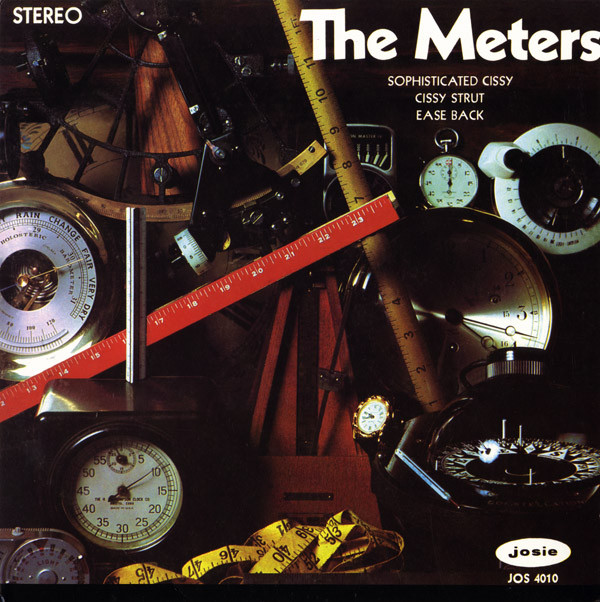

The Meters — The Meters

The Meters’ 1969 debut is a hard pearl of minimal funk formed by compressed grooves and the salty flow of Art Neville’s organ. Opener “Cissy Strut” is canon, but “Here Comes the Meter Man” and “Sophisticated Cissy” show them flexing subtle jazz chordings and easy-morning tones, too. The impact of the New Orleans band on Check Your Head is massive: Despite the brilliance of the playing, the sparse, uncluttered sound of their recordings makes funk seem no less accessible than hardcore.

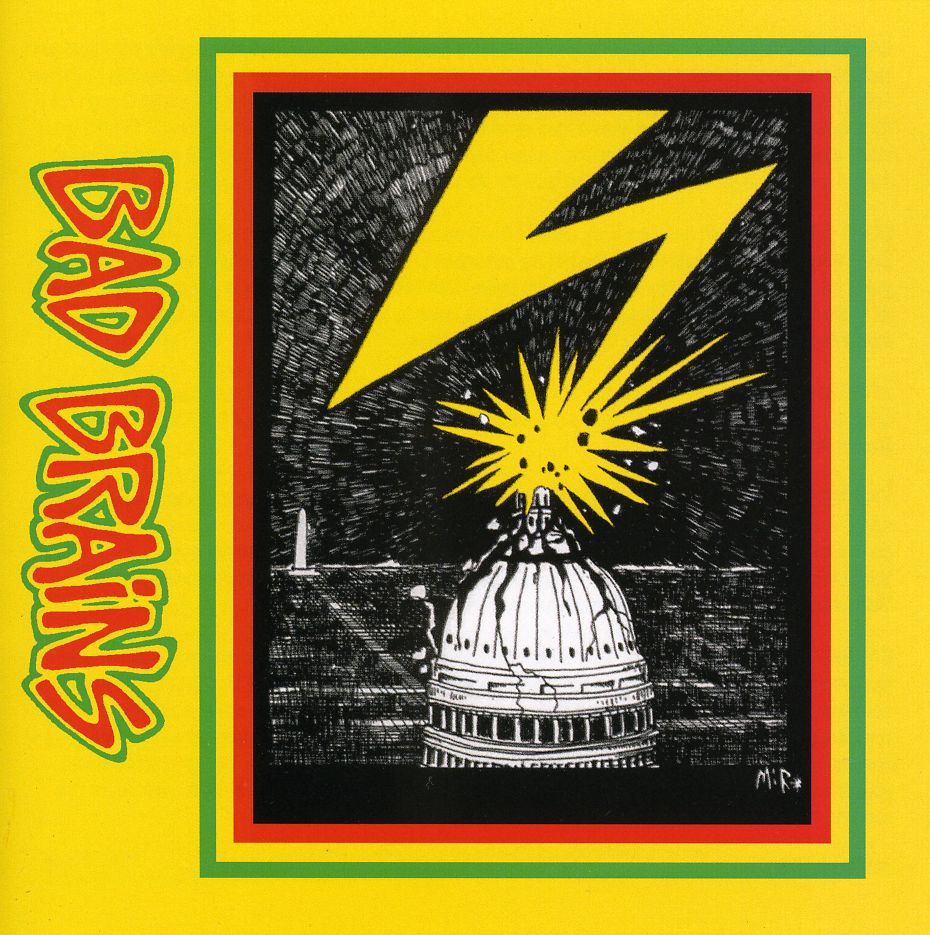

Bad Brains — Bad Brains

Legend has it that when Bad Brains sailed on up to New York from DC, the lightning power of their live show scared bands away from opening for them. While 1986’s I Against I is the likely masterpiece, the self-titled debut from four years prior shoves all of that album’s flourishes—reggae, hard rock, funk—into a ruthless hardcore container. After Licensed to Ill, Yauch teamed up with bassist Darryl Jenifer to form the supergroup Brooklyn, whose song “I Don’t Know” eventually became the base of Check Your Head’s “Gratitude”; Yauch would also produce Bad Brains’ 2007 album Build a Nation.

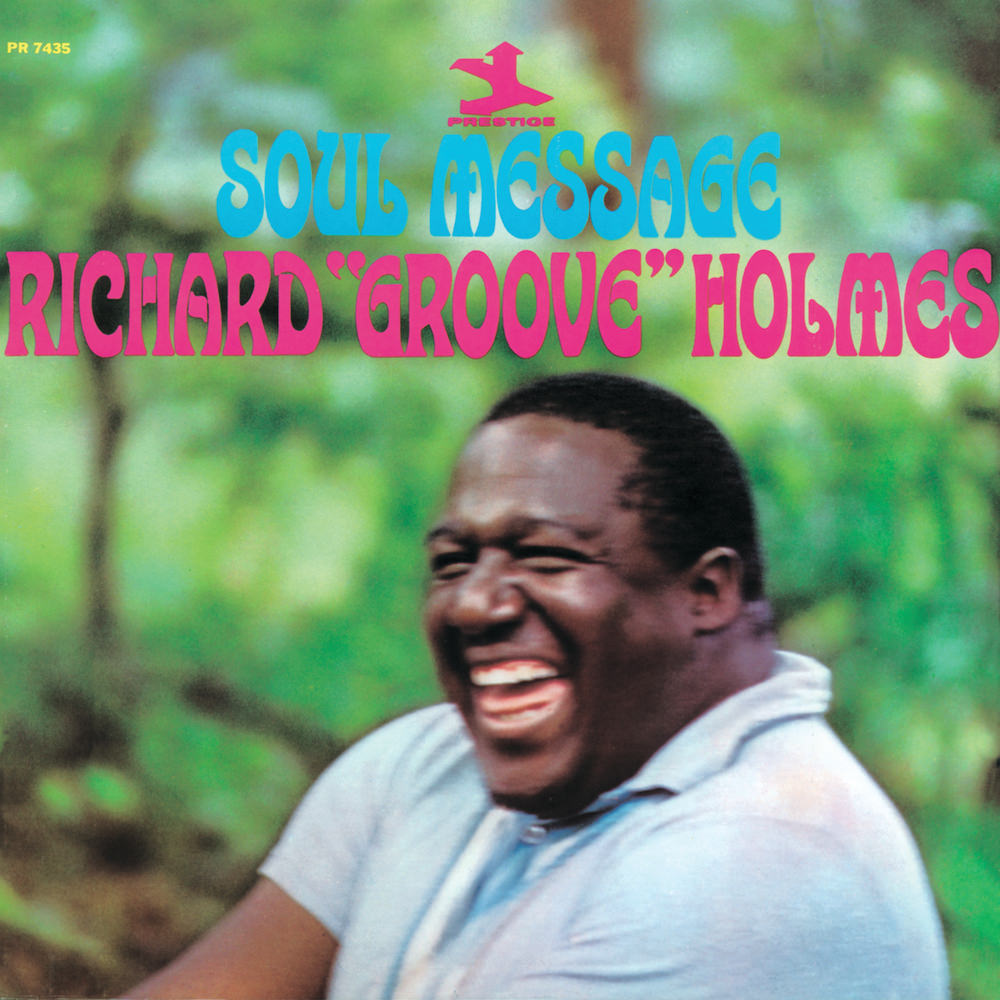

Richard “Groove” Holmes — Soul Message

The music of Richard “Groove” Holmes isn’t cool. It’s not heady like Alice Coltrane or muscly like The Meters, and it doesn’t bop the way The Jazz Crusaders do. But there’s a reason this man, of all the people to ever enter a recording studio, got to take the nickname “Groove.” His playing here at times presages Herbie Hancock circa Head Hunters and at times skirts the stately blues of his contemporary Booker T. Jones. Sometimes it sounds like he’s playing at a ballpark. But he’s always deep, deep in the pocket.

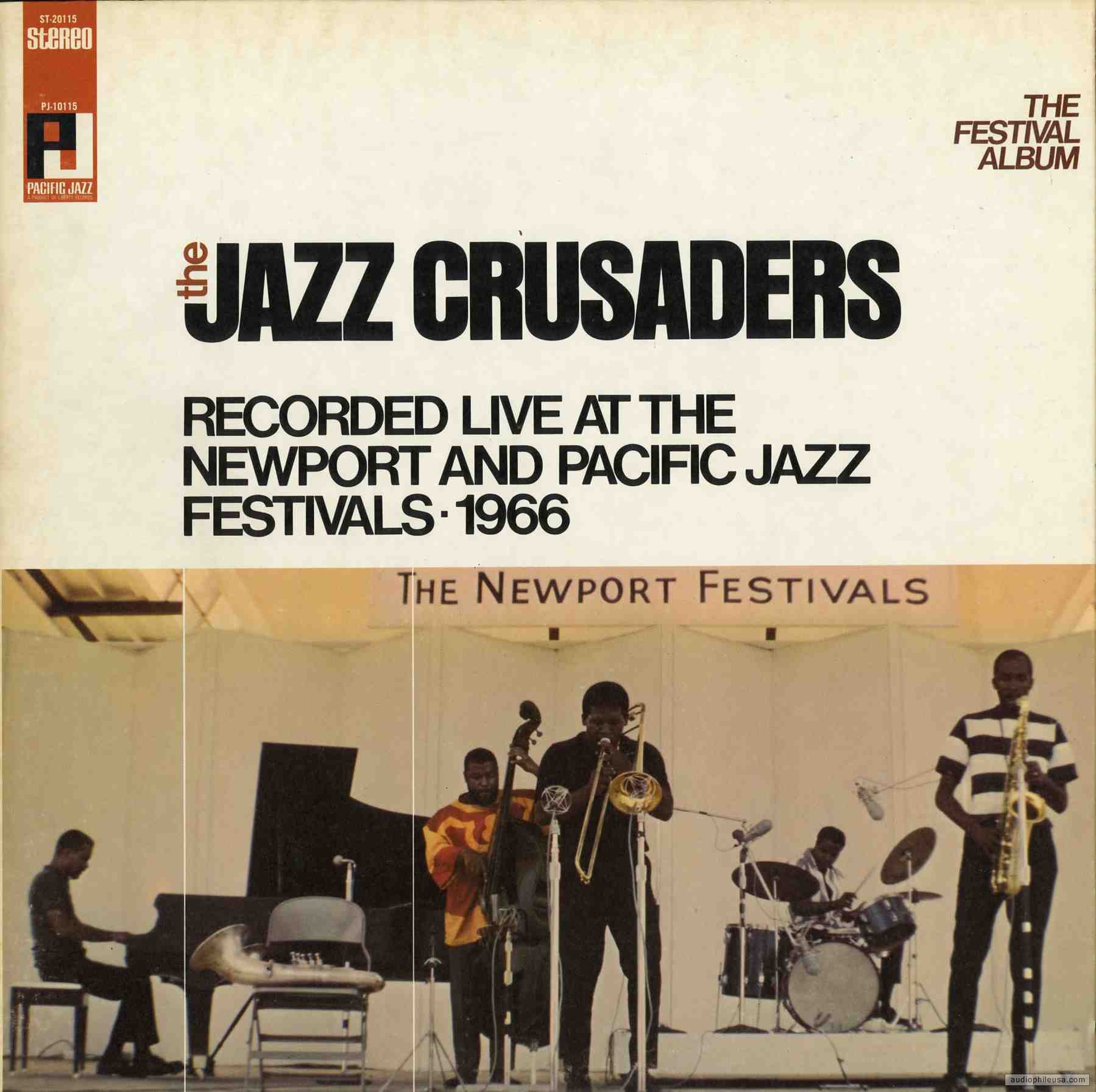

The Jazz Crusaders — The Festival Album

In 1971, The Jazz Crusaders dropped the “jazz” from their name and began playing fusion. This live album recorded in 1966 suggests that they may have reached the end of jazz’s possibilities. The group’s playing at the Newport and Pacific Jazz Festivals is exceptionally tight: It’s formally elegant, delicate where it needs to be, and energetic in all the right spots—listen to them call out to one another off-mic between solos in “Wilton’s Boogaloo.” FL

This article appears in FLOOD 6. You can download or purchase the magazine here.