In Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping, Andy Samberg’s Connor 4 Real shares everything. With his iPhone out, the titular pop star (and former member of the Beastie Boys–inspired rap trio Style Boyz) broadcasts directly to his fans. In addition to being one of the best films of 2016—Criterion edition no doubt forthcoming—Popstar illustrates how open the relationship between star and fan has become. Through Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, and Facebook, we have nearly unlimited access to our stars, and they have a direct line of communication to us.

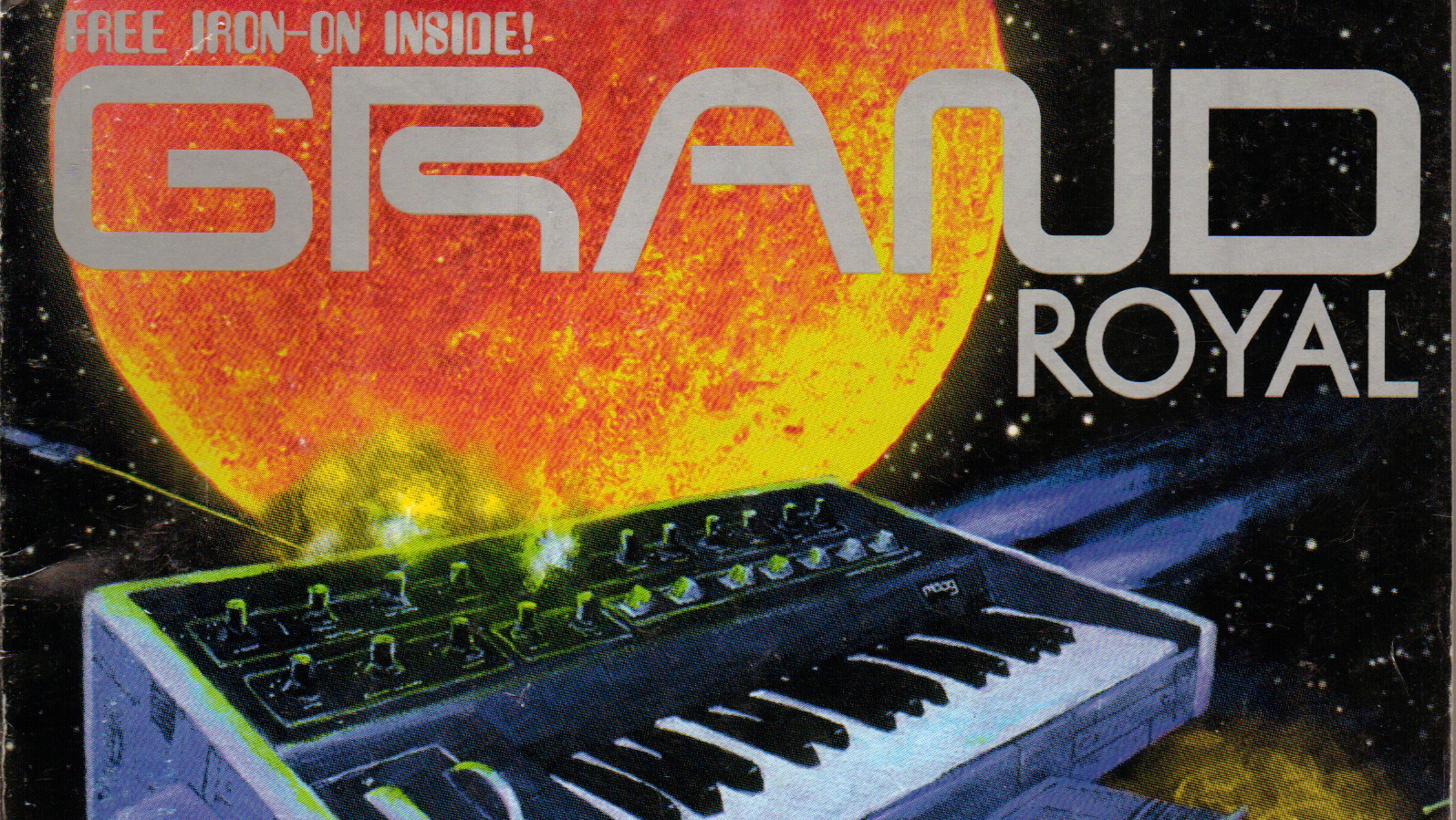

When the Beastie Boys launched Grand Royal magazine in 1993, it was a different story. Video had killed the radio star more than a decade earlier, but pop music still held mystique. The goal of the magazine was similar to that of Connor’s tell-all updates. With Grand Royal, the Beasties could share their pop culture musings directly with an increasingly rabid fan base.

But the idea didn’t start so ambitiously. In a 1997 article in Select Magazine, Mike D stated, “We didn’t sit down and think, ‘Hey, let’s make a magazine.’ We had all of these people writing to us (using the address listed within the Check Your Head liner notes) about the band and we weren’t getting back.” The group figured a newsletter would reach fans, but quickly realized they had the opportunity to do something on a larger scale. Flush with major label cash, they conspired to create “a proper magazine.”

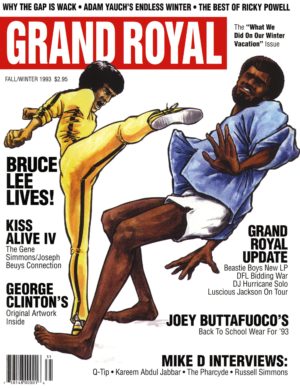

Like the trio’s label of the same name, Grand Royal was sprawling in its diversity. From ’93 to ’97, they published six issues, each packed with content that covered the Beasties’ various passions. Along with friends like Thurston Moore, Kate Schellenbach, Spike Jonze, and Mike Watt, they dove deep into music, basketball, skating, fashion, religion, food, and whatever else made sense (or didn’t). There was little in the way of promotion for the Beasties’ label or even the group itself, but the magazine helped solidify their brand as irreverent, inspired, weird, funny, and often intensely sincere. All three Beasties contributed to the first issue, which featured a comic book–style illustration of Bruce Lee on the cover, but over a five-year stretch, the two Adams mostly stepped aside, leaving the magazine in the hands of Mike D and a revolving cast of editors.

Like the trio’s label of the same name, Grand Royal was sprawling in its diversity. From ’93 to ’97, they published six issues, each packed with content that covered the Beasties’ various passions. Along with friends like Thurston Moore, Kate Schellenbach, Spike Jonze, and Mike Watt, they dove deep into music, basketball, skating, fashion, religion, food, and whatever else made sense (or didn’t). There was little in the way of promotion for the Beasties’ label or even the group itself, but the magazine helped solidify their brand as irreverent, inspired, weird, funny, and often intensely sincere. All three Beasties contributed to the first issue, which featured a comic book–style illustration of Bruce Lee on the cover, but over a five-year stretch, the two Adams mostly stepped aside, leaving the magazine in the hands of Mike D and a revolving cast of editors.

Two decades after it stopped being published, the anything-goes feel of Grand Royal still reads as remarkable. Its pages crackle with energy and seem to encompass everything cool from every corner of the pop culture landscape. George Clinton was profiled alongside Evel Knievel; early coverage of Lil Jon and Kid Rock was published, as was a review of the WNBA’s first season and a list of the best hotel pools to break into in LA. (“I think it’s very moral to swim in hotel pools when you’re not technically staying there,” Jonze wrote). It was ostensibly a “cool bible,” with pieces like “Why It’s OK to Like Metal Again” and a top ten prog rock list offering readers permission to enjoy less-than-hip genres; feral enthusiasm always trumped elitism.

Two decades after it stopped being published, the anything-goes feel of Grand Royal still reads as remarkable. Its pages crackle with energy and seem to encompass everything cool from every corner of the pop culture landscape. George Clinton was profiled alongside Evel Knievel; early coverage of Lil Jon and Kid Rock was published, as was a review of the WNBA’s first season and a list of the best hotel pools to break into in LA. (“I think it’s very moral to swim in hotel pools when you’re not technically staying there,” Jonze wrote). It was ostensibly a “cool bible,” with pieces like “Why It’s OK to Like Metal Again” and a top ten prog rock list offering readers permission to enjoy less-than-hip genres; feral enthusiasm always trumped elitism.

“I think the goal was to put out a cool zine with the Beastie Boys’ power and juice behind it, just to write about cool stuff that they [were] into,” says Peter Relic, who interned and wrote for Grand Royal, and went on to work for Rolling Stone. “It’s a Beastie Boys thing, just throwing a bunch of zest into the pot and making a bouillabaisse out of it.”

“It’s a Beastie Boys thing, just throwing a bunch of zest into the pot and making a bouillabaisse out of it.” — Peter Relic

Even when the magazine took harsh critical stances, as when Mike D reviewed Soul Asylum’s “Whatever the Fuck Their New LP is Called” as “white music by white people for white people,” it did so with canny self-awareness. “I don’t know why I wrote this review,” he went on. “Maybe I’m bitter, maybe I’m jealous, maybe I’m just tired of seeing their milk toast [sic] faces and milk carton video on MTV every five minutes… I can’t defend what I’ve written here, it’s just plain wrong, and more importantly, whatever I think about about Soul Asylum is unimportant since I don’t listen to that Midwestern platinum punk shit anyway.”

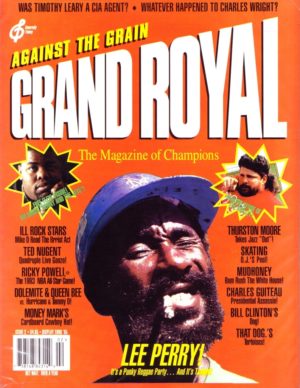

No single issue better encapsulates all that was pivotal about Grand Royal than the second. Featuring Steve Knezevich and Craig Yamashita’s iconic Wheaties-style cover bearing an image of Lee “Scratch” Perry with a giant spliff dangling from his mouth, the issue capped a year-long wait. Grand Royal #1 established substantial hype, but the delay was exacerbated by former SPIN/Spy/National Review writer Bob Mack’s obsessive editing and a generally “relaxed” work ethic (“It was bong rips and Budweiser for breakfast,” Relic laughs).

But the extra time was worth it. Mack’s manic drive fueled and defined Grand Royal’s early days, and those first two issues pulse with gonzo energy. The Perry cover might be the definitive story on the reggae icon, illuminating his arcane methods like few pieces have. Mack sits down with Ted Nugent and things go off the rails almost immediately, the Michigan guitarist shouting the n-word (at least it reads that way; the Nuge is quoted in all caps) and Mack—claiming a staunchly libertarian ideology—rips into Ted over his racism, Damn Yankees, and selling out. It’s hard to fathom how hot the takes would be in reaction to the interview were it to be published in 2017.

The issue boldly steps outside of time, presenting a 1981 interview with Viv Albertine of The Slits by Luscious Jackson’s Jill Cunniff and a Mark Reibling feature that trips through the “secret psychedelic underground,” asking, “Was Timothy Leary a CIA agent? Was JFK the ‘Manchurian Candidate’? Was the ’60s Revolution a Government Plot?”

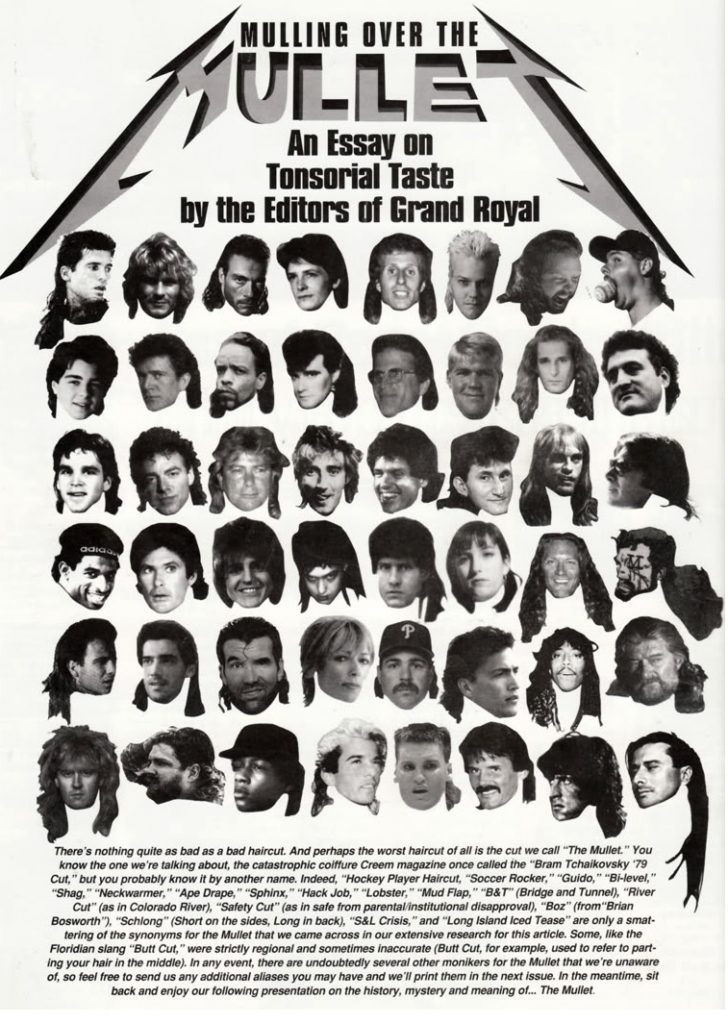

Perhaps most famous of all is the issue’s “Mulling Over the Mullet” spread, a six-page feature that explores the short-in-front, long-in-back hairstyle through the lenses of race, economics, and history. The academic approach is hilarious but not entirely a put-on as it asserts the “social democracy of the mullet.” Mike D even wore a mullet wig for a day, visiting Guitar Center, having lunch at Denny’s, and attending a Hollywood party where he garners “wrathful stares from the glitterati.”

After its sixth issue, the cover of which was dedicated to demolition derbies, Grand Royal folded. Never the most efficient enterprise, the magazine’s sporadic release schedule made selling subscriptions and (more importantly) advertising difficult.

After its sixth issue, the cover of which was dedicated to demolition derbies, Grand Royal folded. Never the most efficient enterprise, the magazine’s sporadic release schedule made selling subscriptions and (more importantly) advertising difficult.

“What’s the spine of the second issue say?” Relic asks. “Long awaited, much anticipated, grossly outdated.”

For a time, the magazine went digital, but that soon ceased as well. And the end of the mag foretold future problems for the Grand Royal label: In 2001, the imprint was shut down after accruing massive debt.

“It was bong rips and Budweiser for breakfast.”

But Grand Royal’s influence—editorial and otherwise—continued on. Contributor Jay Babcock formed the esteemed counterculture guide Arthur—giving voice to the rising freak-folk movement—and part-time editor Spike Jonze went from shooting skate videos and Beasties clips to winning an Academy Award; the cocky attitude and all-encompassing scope of his VICELAND channel is no doubt informed in part by his time at Grand Royal.

Poring over back issues, it’s easy to imagine what it must have felt like for fans to get their hands on these generous dispatches from Beasties HQ. They were guides to unknown worlds, inspired and passionate musings beckoning readers to fall deeper in love with the restless creative spirit that fueled the group. Or, as they described their mission: “Being low-lifes in fine print and birdies with tweet treats, we paraphrase Ornette to say, this is our magazine, or to paraphrase Mad Richard from Verve, this is magazine.” FL

This article appears in FLOOD 6—which features an entire half-side dedicated to the twenty-fifth anniversary of Check Your Head. You can download or purchase the magazine here.