Fourteen years ago, in the middle of what would become his most popular song, André 3000 offhandedly delivered a line that is both prophecy and a tidy summation of the history of conscious pop music: “Y’all don’t wanna hear me,” he sings, and not without some exuberance. “You just want to dance.”

André was probably right, as far as the audience for “Hey Ya!” was concerned, but even 2003—which saw the beginning of the Iraq War, the crash of the Space Shuttle Columbia, and the death of Nina Simone—sounds like a welcome respite from the brutal reality of 2017.

So what’s a pop star to do?

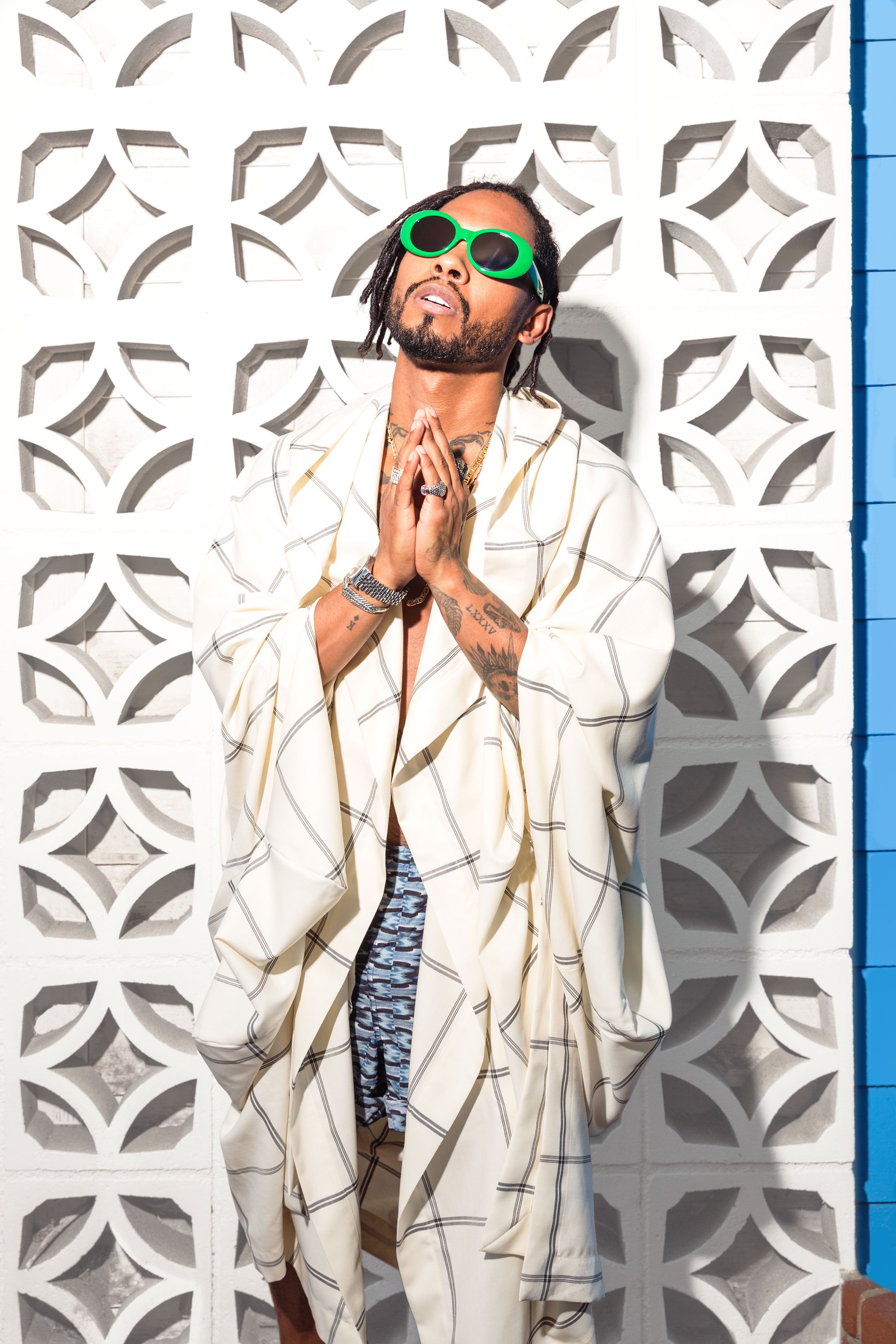

You get the sense that this is a question that bugs Miguel. The psychedelic soul of 2015’s Wildheart was driven by a rich, lusty set of songs that veered from the carnal to the tender in the blink of a perfectly made-up eye. But, to paraphrase Erykah Badu, it wasn’t all betwixt the sheets. The dampness that seems to emanate from Wildheart’s production—most of which Miguel handled himself—comes not only from late-night lovers’ steam, but also from its creator’s humid mind as he tries to locate himself in a world that often seems hostile or alien. It was both an artistic and commercial high point, and it provided Miguel with the kind of platform his charismatic vulnerability seems to have been created specifically to occupy. In a world like ours, though, where—as he put it onstage at Pitchfork Fest in 2016—he’s “tired of human lives turned into hashtags and prayer hands,” doesn’t a musician, like anyone with any kind of influence, have a responsibility to try and make the world a more just place, instead of simply talking about it?

You get the sense that this is a question that bugs Miguel. The psychedelic soul of 2015’s Wildheart was driven by a rich, lusty set of songs that veered from the carnal to the tender in the blink of a perfectly made-up eye. But, to paraphrase Erykah Badu, it wasn’t all betwixt the sheets. The dampness that seems to emanate from Wildheart’s production—most of which Miguel handled himself—comes not only from late-night lovers’ steam, but also from its creator’s humid mind as he tries to locate himself in a world that often seems hostile or alien. It was both an artistic and commercial high point, and it provided Miguel with the kind of platform his charismatic vulnerability seems to have been created specifically to occupy. In a world like ours, though, where—as he put it onstage at Pitchfork Fest in 2016—he’s “tired of human lives turned into hashtags and prayer hands,” doesn’t a musician, like anyone with any kind of influence, have a responsibility to try and make the world a more just place, instead of simply talking about it?

It’s no surprise, then, that he finds himself drawn to Pussy Riot. And it’s hard to think of a better contemporary example of a group whose activism and art are so deeply intertwined. Since two of their members, Nadya Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, were sent to jail for their “Punk Prayer” in 2012, the Russian collective has splintered to pursue various projects—including journalism, activism, and music—all under the Pussy Riot banner. Last fall, shortly after the election, Tolokonnikova used the name to release a three-song EP called xxx that included the electro-pop song “Make America Great Again,” the chorus of which positions empathy as the solution for America’s woes: “Let other people in / Listen to your women / Stop killing black children / Make America great again.” In the accompanying video, she’s branded with a hot iron, sexually assaulted, and humiliated by prison guards for her trouble.

Miguel tweeted a video of himself singing the track (which he rightly called “legit a jam, feel good even!”) in a Hawaiian shirt, his body moving gracefully through the dips in the song’s melody. In his hands, “Make America Great Again” softens, and Tolokonnikova’s protest becomes his plea, and for the listener, the line between the two concepts is blurred beyond recognition.

So, as he puts the finishing touches on his fourth album, War and Leisure, which is led by the legit feel-good jams “Sky Walker” and “Shockandawe,” the question lingers, and more besides. What is the role of the artist in 2017? Does anyone need to hear an R&B singer’s take on the world? How do you “celebrate every day like a birthday,” as he puts it in “Sky Walker,” when the threat of nuclear war lingers overhead?

To try and answer them, FLOOD called up Tolokonnikova in Moscow, where she was preparing for a video shoot in a room decorated with a sign reading “good night white pride,” and linked her together with Miguel, who was beginning his morning in Los Angeles in a plush red robe, goblet of orange juice in hand. After expressing a frankly giddy appreciation for one another’s work and laughing about their mutual friend Dave Sitek’s habit of sending oddball picture texts, they got down to the serious business of being pop stars, beginning with the genesis of Pussy Riot’s “Make America Great Again.”

Nadya Tolokonnikova: I hadn’t been to America for a while, and then when I was in Moscow, I heard about Trump. It was the summer of 2015, and I was scared to go, but I still jumped on the plane and went. So I decided to use art as political psychotherapy. I think that’s the best kind of psychotherapy, because you don’t need to spend money on shrinks, and you just deal with your own neuroses. That’s how that song happened.

Miguel: People don’t understand how difficult it is to be clear and concise and to deliver a real message. And I think that’s one of the things that I love about what you do: It’s so clear, and melodic, and clever.

Among punks, you’re supposed to hate pop things, right? But I believe that you need to learn from—not all pop culture, but from some parts of pop culture, how to be precise. There’s [a thing that happens] when you’re developing underground political discourse: You start to be so complicated, and sometimes you don’t even understand yourselves. You need to figure out how to question the status quo and be popular at the same time.

Information isn’t always popular. And so in making information popular, you sometimes have to make it digestible for the masses, you know? For people who aren’t [naturally] critical thinkers or who aren’t going to question the status quo. You’re smart enough to go, “OK, I did all of the work to understand why I believe this, so let me condense all of that and make it something that you can really understand.”

Look at Trump. He’s a douchebag, but he’s making everything super clear; he’s literally speaking in slogans. So in order to oppose him, you need to be clear, too, and you need to come up with better ideas than him.

Look at Trump. He’s a douchebag, but he’s making everything super clear; he’s literally speaking in slogans. So in order to oppose him, you need to be clear, too, and you need to come up with better ideas than him.

It’s crazy how appealing to people simple emotional things are, and how powerful simple emotional triggers can be. I mean, that’s what music is, really. And he’s learned how to do that—or he’s figured out how to manipulate it masterfully.

How are you dealing with the news? Every time I open the news, I feel like I’m overwhelmed with despair or anger—or empathy, on the other hand. You want to be connected with reality, but at the same time you need to overcome your terrible emotions every day.

“[Artists] need to figure out how to question the status quo and be popular at the same time.” — Nadya Tolokonnikova

Watching the news now feels like watching a soap opera. So it’s hard to take anything seriously, even though the planes that flew over North Korea—that really happened. And the missile that was fired over Japan—that really happened. No matter how I’m getting the information and how absurd the reason behind it is and why it’s happening, I always try and remind myself that war and conflict are—well, it can all be whittled down to greed. And it’s gonna be here until we as a culture—or as just humans—really elevate. So I think my biggest way of dealing with it is reminding myself that, at the end of the day, it’s about elevating our consciousness and our need to be connected with each other.

My contribution—and the best way I can contribute—is through my music. So what in my music can I do to bring people together? And I think that’s what has been the driving force behind the music that I’ve been creating for this project. But the more fragmented we become, the less empathetic we become to each other’s positions and experiences.

Definitely. I think greed and dehumanization are giant problems, because you start to treat people as merely instruments for achieving something. That’s how Trump and Putin happen. When you’re labelled by someone—“You’re Russians”—you’re not a human being anymore; you’re less than a cockroach.

Definitely. I think greed and dehumanization are giant problems, because you start to treat people as merely instruments for achieving something. That’s how Trump and Putin happen. When you’re labelled by someone—“You’re Russians”—you’re not a human being anymore; you’re less than a cockroach.

And you feel it, too. When I come to the American border with a Russian passport, I see their reaction. And I’m really concerned with that because it’s a deep scar, and it’s maybe for one generation, or maybe for two or three. Even after Trump’s term comes to an end, we’ll have someone else. So you will still, as a culture, be like, “Oh, the Russians.” Because he’s gone back to this Cold War paradigm.

It’s taken decades [for our countries] to repair their perspectives [toward one another]. And not only with our relations with people from different places… He’s enabling Nazis inside of the United States—literal Nazis that are not in hiding anymore.

Walking around with torches.

The cat’s been let out of the bag. Like, there’s a population of people in the United States who clearly believe that they are better and deserve more than anyone else. And that’s something that’s going to last after Trump leaves; four years from now, that’s still gonna be there. So how do we deal with that?

“Information isn’t always popular.” — Miguel

You said before that we need to interact with each other more. It’s terrible what’s going on, but it can help us to move somewhere else. There are good and bad sides to it; we’re living in a pretty shitty political situation, but it makes us act and create alternative resources and alternative institutions.

How long were you in jail, by the way? A year?

Two years.

Two fucking years.

And I know it sounds pretty bad, but it really made us stronger—and more convicted.

Freedom of speech is so valuable. If you start [restricting it], that means that people can’t even dream. Do you know what I mean? You can’t even dream now.

That’s another thing I wanted to talk with you about. I look back a lot on the ’60s, and it seems like it was a time when people really dreamed, and dreamed about how to combine politics and their everyday lives. Now, when you think about political engagement, most people still think of that as something boring—like a duty. But if you look back at what was going on in Paris in 1968, or with Martin Luther King, the hippies, the Civil Rights movement, they achieved a lot because they believed in politics. It was exciting for them. It was a transgressive moment.

The dreaming is the catalyst for action. But overall, it always comes down to money and survival. People are like, “Yo, I don’t got time for that.” We’ve become so desensitized to so much. It’s easy, for instance, when a natural disaster happens, to post a photo and say, “Pray for this place.” And then you feel like your duty is done. That’s the kind of apathetic and lazy way we’ve come about supporting things that are good.

Whereas before, especially in the ’60s, you look at here in the States we had a large middle class. You had people that had a living to fight for; they believed in that. And they had something to aspire to. Whereas now, there is no middle class. There’s only the upper 1 percent [and then the rest]. Your focus is only on money, especially in a culture [like ours] that’s built on money. It’s not about family or being together.

Surely, but I would say that that’s true about Russia, too—this greed and [the idea that] we don’t really trust each other.

And the government is a macro example. As you go down, from the government of a country to its smaller states, its cities, its communities—at the very bottom it’s family. If you break the family unit, then you lose trust, you’re losing the support system, you’re losing the community—which means the community has nothing to believe in or fight for. So then it’s just money at the forefront. It’s survival. And when you’re just playing for survival you’re not thinking about tomorrow.

We need to rebuild it somehow; we need to reinforce love and trust. That’s not easy. And that’s why I love art—because art to me is a harbor where I feel connected to people in building community. I’m not a religious person in the normal sense of the word, but I feel art is something religious for me. That’s why we called our action “Punk Prayer.”

I love that. It’s about the community—and inspiring each other to create. Because in a world where there are so many reasons being put in our face not to trust one another, and not to be connected, and to hate each other, I think we need as many people fighting to bring people together for all of the right reasons as we can.

I love that. It’s about the community—and inspiring each other to create. Because in a world where there are so many reasons being put in our face not to trust one another, and not to be connected, and to hate each other, I think we need as many people fighting to bring people together for all of the right reasons as we can.

So this album for me is the most upbeat. You know, you go back and you study the things that you did that you like and you’re like, “OK, cool, what can I do different?” And that’s the one thing I’ve never done, to kind of just focus on making people feel good. To your point, pop music: It’s normally upbeat, up-tempo. Simple. Melodic. OK? When I can do that, everyone is in the same room. Then I can say whatever I want; you’re already here because you want to be.

Speaking of hopes and inspirations, the new generation of kids are a great inspiration. If you look at who’s supporting Bernie Sanders, who’s supporting Jeremy Corbyn, who’s supporting Alexei Navalny (who’s running against Putin here in Russia)—their supporters are young people. Sometimes I speak with seventeen-year-olds and I’m like, “Hey, you’re not really a lot older than my daughter, but you understand more about politics than I do.”

They haven’t forgotten how to dream. That’s the dope part. The youth have the energy and they’re not as washed out by their experience, you know?

They’re not so balls-deep in stereotypes.

They’re allowing themselves to believe and to challenge their own ideals. They’re challenging the ideals of what they’ve been taught growing up. As we start to see the youth grow and all of their amazing ideas take form, it’s gonna be important for us to continue watering those plants. How do we continue giving them what they need so that they, in turn, do the same thing for the younger kids that are gonna grow up with fresh ideas, pushing the boundaries and bringing people together?

Music for me used to be about me. And now it’s like, “Oh, wait a second, all of my heroes are dead.” Bowie, Prince, Michael. A lot of the legendary people who shaped the shit that we listen to now and model our shit after are either old or they’re gone. So the time is now for us to do it.

[We have to] be in charge of our own time. Dave [Sitek, of TV on the Radio, who collaborated with Miguel and produced xxx’s “Straight Outta Vagina” and “Organs”] always says when we write something that he wants to inspire kids, that he makes music for kids: “I don’t like those songwriters who’re writing complicated constructions just to show how smart they are.” That’s why I love Dave.

That’s what he says! He’s like, “No, this isn’t for us; it’s for the kids.” You gotta just create and let it go. He’s the best. But it’s hard in a world where everyone is trying to prove why they deserve attention—and that’s the ultimate currency. It’s something we have to be mindful of. Someone like Dave could easily be like, “Hold on, do you know what I’ve done? Do you know what I’ve contributed?” He easily could. And you! But that shit doesn’t get us anywhere.

It doesn’t. Maybe we would get better careers if we behaved like that, though.

Nah.

It’s important for artists to control that shit inside us. Our culture encourages us to just think about ourselves, and about our representation.

It’s true.

You just have to remind yourself every day, every minute, like just—[snaps]—stop right now.

I can honestly say, just from the past year and a half, working at that part is so freeing. You open yourself up to way more possibility, because you’re no longer criticizing everyone and yourself simultaneously. You’re just trusting your gut to go, “Hey, this feels right, I believe in this.” And leading with love as opposed to leading with a wall. No one wants to climb a fucking wall to get to you; no one wants to do that.

It’s a tough game, but it’s worth it.

It’s a tough game, but it’s worth it.

Yeah, it’s always worth it. And somehow everyone has their thing—we all have our way of contributing. For you and I, we love music. But there’s someone out there who loves to teach. There’s someone out there who wants to figure out what they contribute through science. Everyone has their thing, their real interest, even if it’s someone who’s like, “I just love to garden.” It’s really just about getting to like what we really want, as opposed to what we’re being told to want.

Because the truth is, what we all want is similar. We want love. We want to be acknowledged. We want to feel valuable. And when we can change the order of which things are important in our collective consciousness, that’s when we change the game. We’re at a point in our human history where we have to make some big changes, or we’re right at the edge of war. We’re right at the brink of it all, you know?

And we disappear as humankind.

Exactly. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 7. You can download or purchase the magazine here.