Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith sees music. Ever since she was a kid growing up on Orcas Island, Washington, the electronic composer has visualized sound. Perhaps that’s why her new album The Kid feels so cinematic, its blend of swelling new age ambiance, experimental pop, and cosmic poetry powerfully evocative of color and movement. It’s her sixth solo album, and it follows an intensely productive period for Smith that’s found her recording an album-length collaboration with synth pioneer Suzanne Ciani and performing at desert festivals like Marfa Myths, FORM Arcosanti, and Desert Daze.

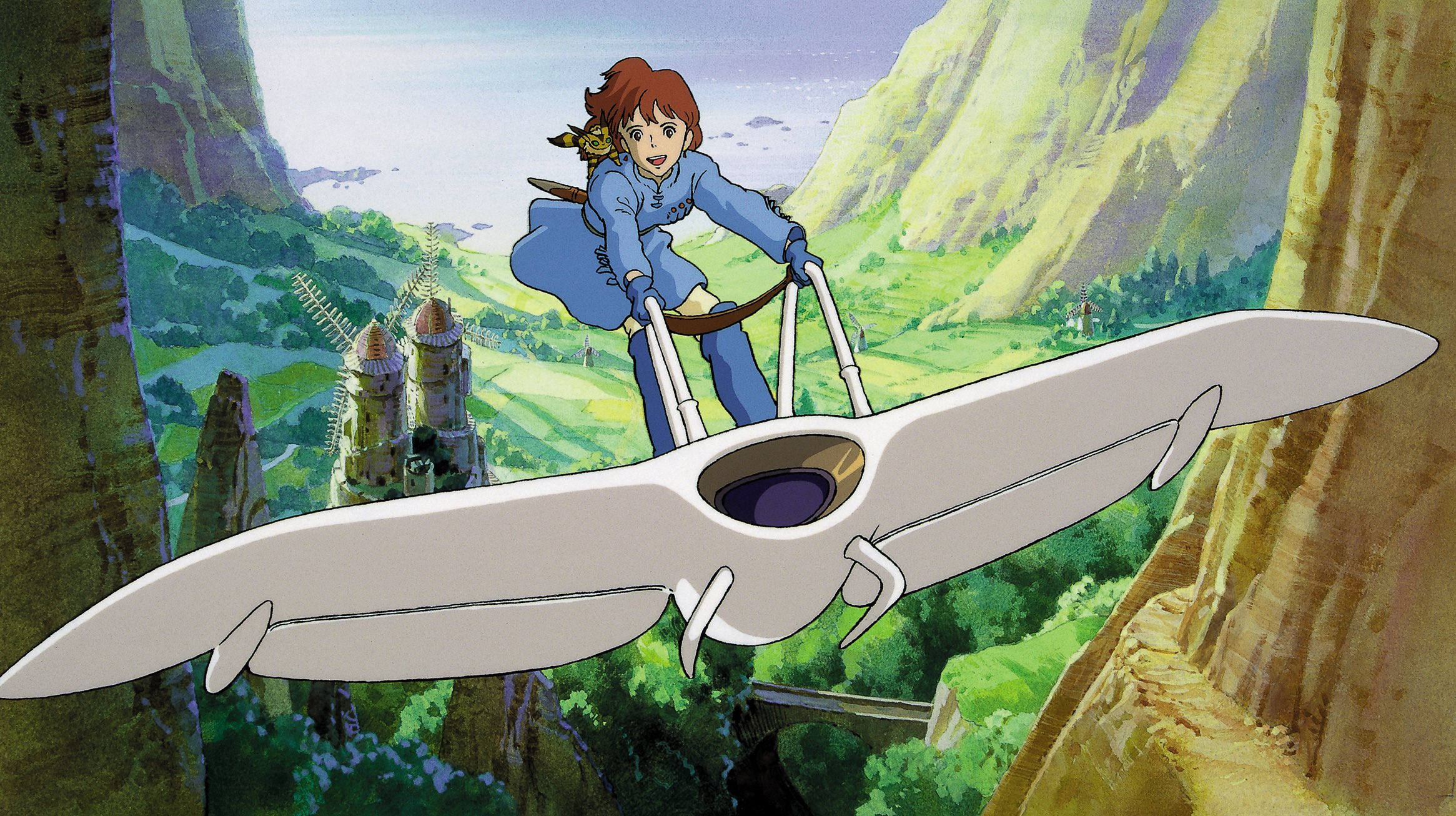

Add the tracklist of The Kid up, and it constitutes a poem: “I Am Learning / To Follow and Lead / Until I Remember / Who I Am and Why I Am Where I Am,” it partially reads. This sense of scope, of overarching and overlapping meaning, syncs up with the work of one of Smith’s primary inspirations: the Japanese filmmaker and animator Hayao Miyazaki. Since she first encountered his work seven years ago, he’s served as a touchstone for the composer; her 2016 album EARS was originally conceived as an alternate soundtrack to his 1984 film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

Smith spoke to FLOOD by phone while she was walking through LA’s Atwater Village about her relationship to Miyazaki’s work.

I recently listened to your great interview with Suzanne Doucet for the Light in the Attic podcast where you talked about “seeing” music. Have you always visualized music?

Yeah, [and] I actually didn’t know that other people didn’t. I thought that was just how it worked. [When I] went to college, that’s when I learned it’s not everyone’s experience. I didn’t utilize it as a tool when I was younger; I just accepted that that’s what it was and was like, “Oh, don’t you see that this is this and this is this?” People would be like, “No.” [Laughs.]

Has Miyazaki’s animation influenced the way you see things?

No, it was more that when I [first] saw those films, it really struck a chord in me; [I felt like he] had made a visual language for a lot of things I feel. Every part of the animation had so much life and wiggle. That’s how I’ve always wanted to hear the world and see the world and experience it, just everything having so much life. I was really excited when I saw them, because I was like, “Ah! They nailed it.” And Joe Hisaishi nailed the music, too. Everything was perfect.

What was the first Miyazaki film you saw?

Princess Mononoke. That one’s amazing. It just opened the gate and I was like, “I have to see everything. Ten times.” [Laughs.]

What’s your favorite of his works?

It’s actually the one that I made EARS [as a soundtrack] for: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. I didn’t really say it too much publicly, because I’m such a big fan of Joe Hisaishi; I didn’t want it to sound like I was trying to replace his work in any way.

You used the phrase “wiggle” in regards to your attraction to his work. When I listen to EARS, it feels like it has a lot of that. It evokes an organic feeling, like it’s mimicking natural processes of plant life—blooming, growing.

That’s great! It worked.

Do you get that from Miyazaki’s work? It feels like there’s a special attention paid to life processes in his films.

“That’s how I’ve always wanted to hear the world and see the world and experience it, just everything having so much life.”

It’s hard for me to say that’s what he intended, but that’s what I get out of it. I feel like the way I look at the world is similar to the way I look at tarot cards—you pull from it what you want to get in that moment. Nothing’s actually telling you anything; you’re reading your own experience into it. That’s what I get out of his films. I’m always inspired and seeing movement and flow and growth.

When you watch those films, it’s like you’re reading sacred texts; it’s all in there. On “An Intention” from The Kid, you sing, “I feel everything at the same time.” With this record, did you have it in mind to make a similarly grand statement as Miyazaki, just about the enormity of existence?

It was just kind of my experience at the time. Someone really close to me passed away. My dad has been talking a lot about the four stages of life. It’s a constant theme. I’d just seen this movie that provoked the whole idea of holding on to your “kid” energy for dear life.

Which movie?

It’s so sad. It’s called The Tale of Princess Kaguya. It’s another anime film [by director Isao Takahata, released by Studio Ghibli, which Takahata co-founded with Miyazaki]. I promise I watch movies that aren’t anime, too [laughs]. It’s so beautiful; I cried the hardest I have in ten years watching it. I got this amazing feeling from it that there’s no time to waste, so just play. That was something really strong in me creating [this record].

[Comic artist] Mœbius is a big one for you too, right? Do you get a similar feeling from his work that you do from Miyazaki?

Yeah, [and] I think it has to do with color hue choices; I’m drawn to when someone has a consistent language with their sense of color. Where there’s people who have really strong contrasts, it’s not that it doesn’t resonate with me or I don’t like it—it’s [that] I’m more particular about it than when there’s gradients and it looks more like a transcendental art piece, like something Frederic Church would paint. It’s representative of what I would find in nature but there are little exaggerated parts. I think I’m also drawn to things that illustrate how small of a role humans have in nature, but how big of one they think they have. That’s something I’m always trying to remind myself of.

And that’s an idea that runs through many of Miyazaki’s films. Does that idea freak you out—the idea of how small we are in comparison to essentially everything else?

That’s kind of what the last song on [The Kid] is about: this bittersweet feeling of how beautiful it can be to approach death and regeneration, renewing energy—but also how sad it is that what you knew is not going to be there anymore. So it doesn’t freak me out; it’s my nature to move toward things I’m really bad at and afraid of. That’s something I get joy out of and have a lot of curiosity about. FL

This article appears in FLOOD 7. You can download or purchase the magazine here.