Miguel

Miguel

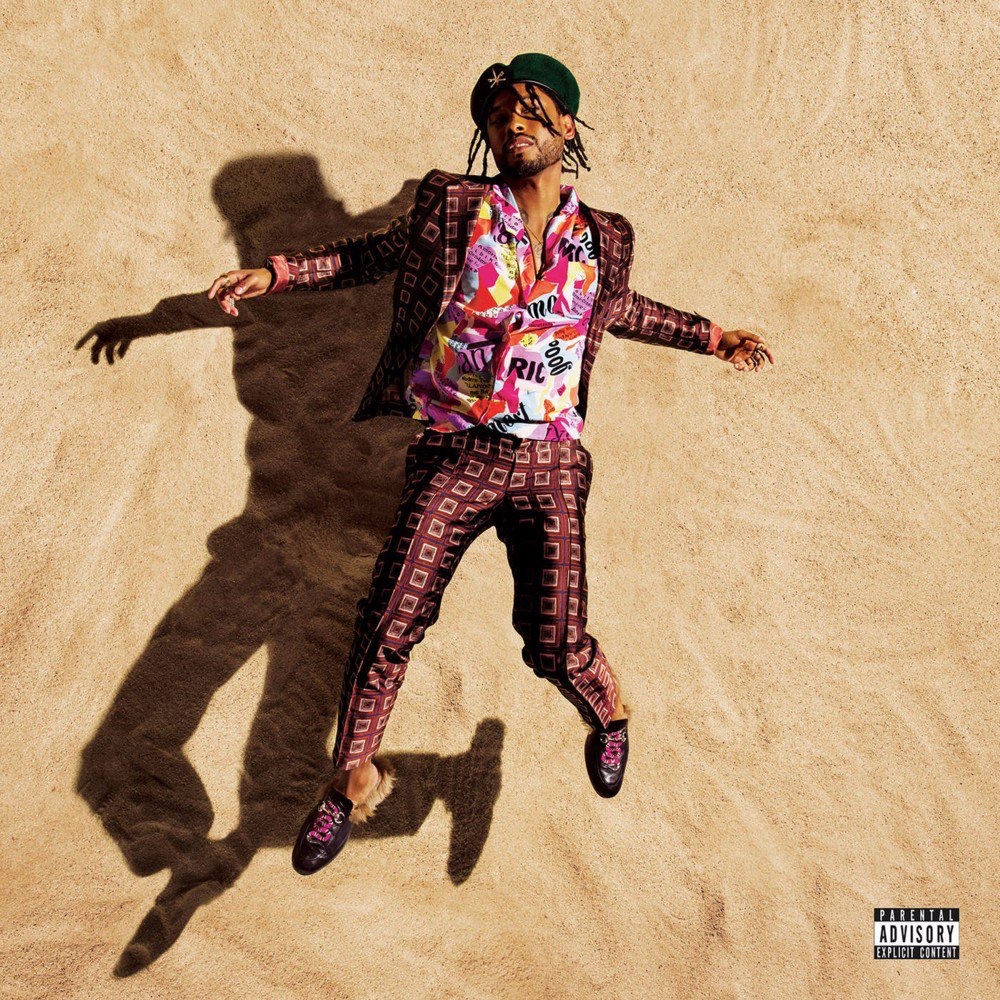

War & Leisure

RCA

8/10

In his cover story with Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova for FLOOD’s current issue, Miguel said, “Music for me used to be about me. And now it’s like, ‘Oh wait a second, all of my heroes are dead.’ Bowie, Prince, Michael… So the time is now for us to do it.” Indeed, making music at its best is a kind of altruism, and in desperate times led by ugly voices, Miguel is feeling heroic. On War & Leisure, he pirouettes through pandemonium, bringing some peace to all in his path.

At face value, War & Leisure may seem far less political than promised—there isn’t a morose meditation on society like “Candles in the Sun” or “What’s Normal Anyway” from his previous albums—but it takes a few listens to detect his subliminal themes. On soaring opener “Criminal,” he repeatedly name-drops “5150,” the California police code for involuntary psychiatric hold, which many in the entertainment industry have come to know too well; from the jump, he’s confronting the darkness in his midst with a smile. He makes a cascading chorus out of the harsh word “backslide” on “Pineapple Skies,” and on “Banana Clip,” which is a slang term for a rifle magazine, he satirizes gun talk in pop, converting bullets to love notes.

Miguel is adamant about the categorization of R&B being racially instituted and inaccurate of his sound, and War & Leisure feels equal parts pop, psychedelic rock, disco, hip hop, and funk. On certain points of Miguel’s largely self-produced last LP Wildheart, he seemed to unflinchingly channel Nate Dogg and Black Sabbath at the same time, an approach that proved exhilarating for some and unsettling for others. But with War & Leisure as his fourth full body of work, he’s solidified a definitive Miguel sound that contextualizes past efforts: the fuzzed-beyond-all-recognition guitar riffs, subterranean bass synths, and drums that feel like they’re being aurally clotheslined, setting a fierce foundation for saintly vocals. The majority of pop music today builds from some quantized four-bar loop, but Miguel often uses analog instruments, played throughout the song rather than copied and pasted, arriving at more timeless qualities of songwriting.

Though Los Angeles is home to every kind of musician, few even begin to capture the city’s true energy. With album standout “City of Angels,” Miguel enters the stratosphere of Chili Peppers and Eagles with a tale of war on the West Coast: “When the City of Angels fell / I was nowhere to be found,” he sings, afraid that should tragedy ever strike, he’ll be in the middle of fooling around with someone else. It’s a classic LA take on the fateful consequences of seduction, its down-picked distorted guitar even echoing Black Flag. The image of Hollywood ablaze feels less outlandish each passing day now, but Miguel is a Voltairian: “Life is a shipwreck, but we must not forget to sing in the lifeboats.”