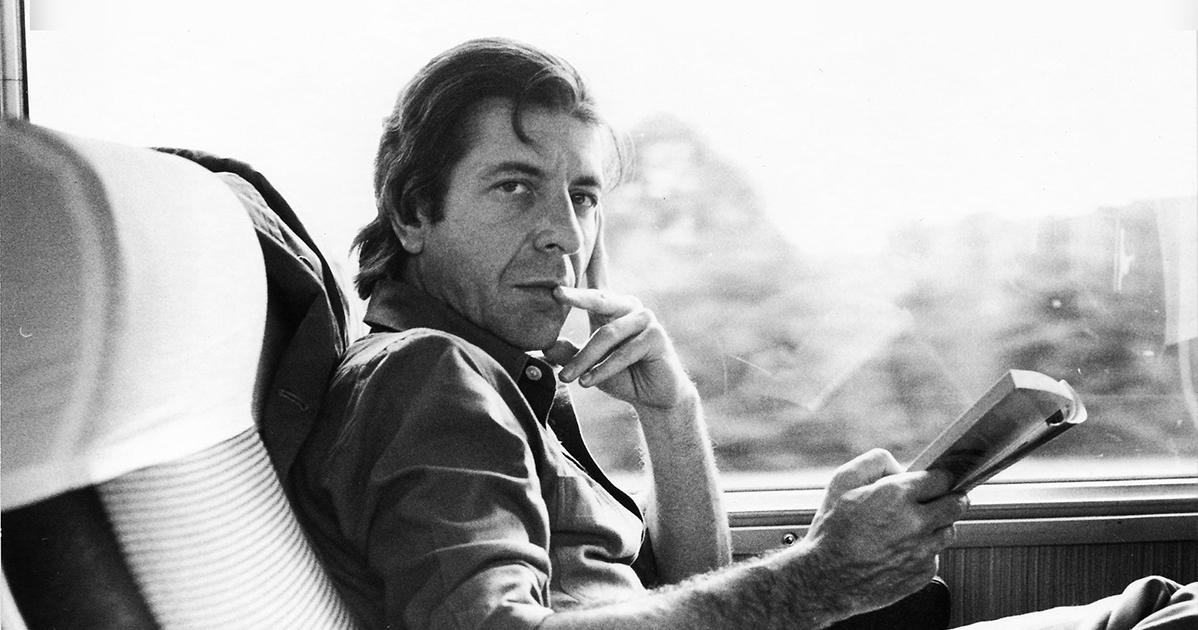

The year since Leonard Cohen’s death has provided us plenty of time to reflect on the work of the poet-turned-troubadour—even if much of that reflection has come in the form of comparing the results of the 2016 American election to the lyrics of “Everybody Knows” (“Everybody knows the good guys lost / Everybody knows the fight was fixed / The poor stay poor, the rich get rich”). But current events aside, it doesn’t take much heavy lifting to see the effect that Cohen’s eighty-two years and fourteen albums have had on the modern music. (See: Nick Cave, The National, Sufjan Stevens, Bright Eyes—and just about every artist that’s covered “Hallelujah.”) With their extraordinary exhibition, A Crack in Everything, open until April 2018, Musée d’art Contemporain de Montréal (a.k.a. MAC) has taken this exploration one step further, and proved that Pop’s Poet Laureate has left an indelible mark on the art world as well.

Before his death, Cohen greenlit the exhibition, part of Montreal’s year-long three-hundred-seventy-fifth anniversary celebrations. His passing does color much of the art on display, the majority of which uses Cohen’s words, music, and images in some form. The tone is set by The Offerings, the opening installation by Kara Blake, which features performance and interview clips, projected on full-wall canvases. Hearing a younger Cohen declare “The older you get the lonelier you get and the deeper love you need” and “I always wanted to be loved by as many people as possible,” it becomes almost impossible to wonder if he left feeling like his mission was accomplished. Was he fulfilled? The following forty artists on display all seek in some way to unpack that question, exploring connections between identity and admiration.

Kara Blake’s “The Offerings” / photo by Sébastien Roy

South African artist Candice Breitz’s lighthearted video installation, I’m Your Man (A Portrait of Leonard Cohen), further taps into this idea of individual interpretation. Viewers are placed in the center of a dozen video screens, as a collection of Montreal men over the age of sixty-five chant-sing “I’m Your Man.” Not only is it straight-up entertaining to see an amateur chorus attempt to imitate Cohen’s gravely baritone (read: they all have a very casual association with pitch), it further drives home how much we see art (and—let’s face it—the world in general) through our personal experience. Then again, Breitz seems to ask: Does it really matter as long as we’re connecting?

Janet Cardiff’s The Poetry Machine takes concept one step further, encouraging viewers to interact with Cohen’s work. By hitting keys on a Wurlitzer, the audience creates an on-demand reading from Cohen’s The Book of Longing. Hitting multiple keys results in a Cohen poetry remix. Given how much weight his words have been given through the years, and how many times they’ve been interpreted (both Cambridge and Montreal’s McGill University offer courses in Cohen), the occasionally inspired juxtapositions still open up new possibilities. That is, until someone discovered page forty-two, where Cohen compares clairvoyants to spiders. (“If you are not sure which mystics are poisonous, it is best to kill the one you come across with a blow to the head using a hammer or a shoe or a large old vegetable.”) The room, too engaged to switch things up, burst into laughter—many discovering for the first time that not only was Cohen wise, he was straight-up funny.

The Sanchez Brothers’ “I Think I Will Follow You Very Soon” / photo by Sébastien Roy

But it was the Sanchez Brothers’ mixed-media piece I Think I Will Follow You Very Soon that managed to capture how difficult it is to figure someone out by what they’ve left behind. The viewer is left stuck in a replica of Cohen’s work space, complete with benign details like a closed Macbook, box of Kleenex, and water bottle—the artist himself seated outside the window, frustratingly out of reach, back to his audience.

Throughout his life, Cohen had modest goals for his art, once going so far as to say, “And I had not much of a voice. I didn’t play that great guitar either.” So perhaps the art world’s standing ovation would have been an overwhelming honor. But then again, that statement, too, falls under the umbrella of speculation and interpretation. In his own words, Cohen’s gift was providing us with whatever we needed, and now that he’s passed, as highlighted by A Crack in Everything, he belongs to all of us.

If you want a lover

I’ll do anything you ask me to

And if you want another kind of love

I’ll wear a mask for you

If you want a partner, take my hand, or

If you want to strike me down in anger

Here I stand

I’m your man