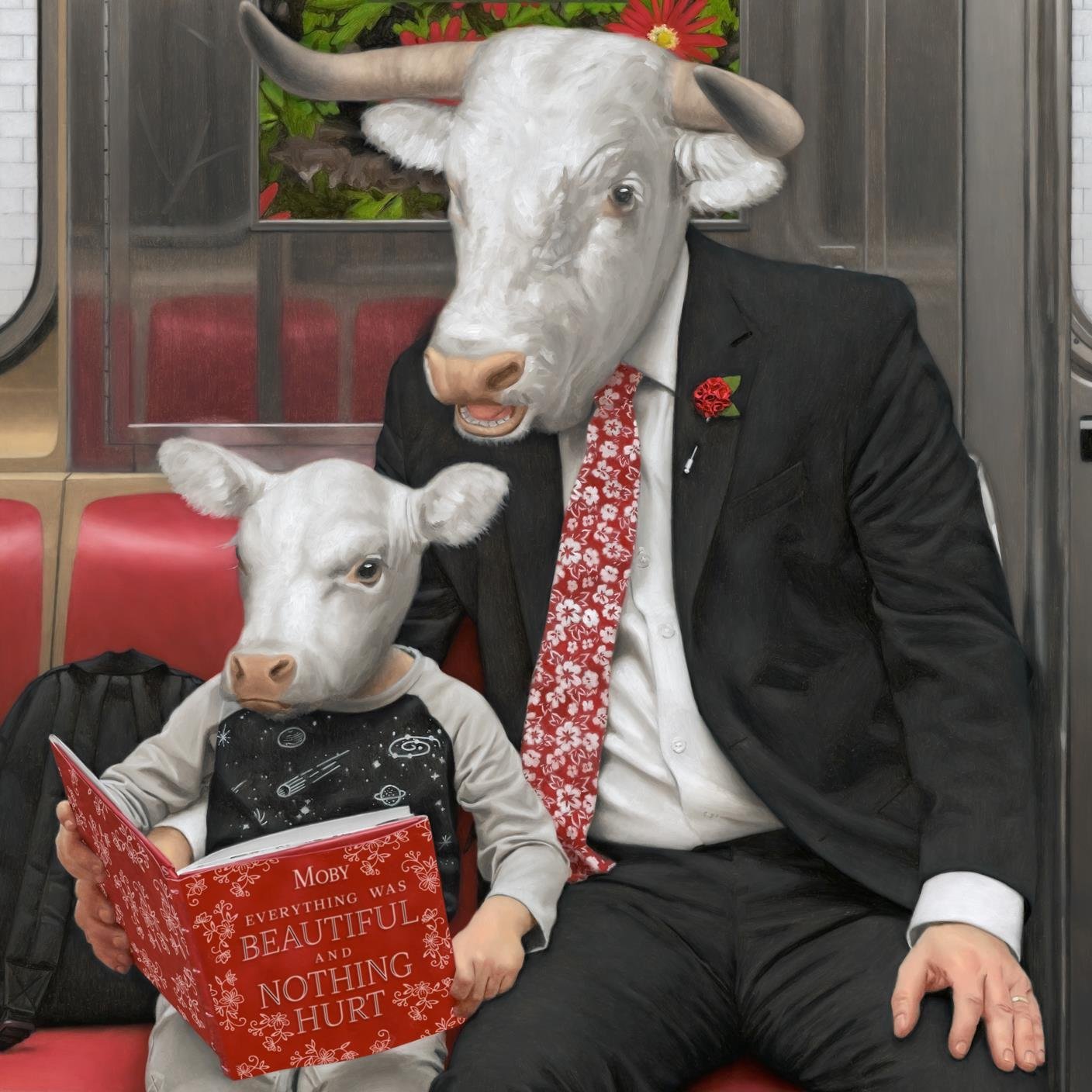

Moby

Everything Was Beautiful, And Nothing Hurt

LITTLE IDIOT/MUTE

6/10

Parental advisory stickers were introduced in the increasingly conservative ’80s to warn parents that their underage progeny were about to embark on a life of failure, drug use, and jail time if they listened to the latest rap and heavy metal offerings. Their actual effect was to identify such horrors for easier targeting by said progeny—a youthful badge of approval, if you will. They have since become meaningless, as most modern pop music strives for maximum acceptance over confrontation—and kids don’t listen to their parents anyway. The new Moby album—Everything Was Beautiful, And Nothing Hurt—might, however, necessitate the re-instigation of such a warning system, and not just for parents; playing it has the potential to render a listener too depressed to get off the couch. It’s a bummer, man—albeit a great-sounding bummer.

Conceptual in nature, the album was apparently conceived in line with some of the more pessimistic dictates of eschatology, or the theological study of death and judgment post-apocalypse. Cheery stuff. The album’s subject matter revolves around a Matrix-like story of life in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, with two songs thematically referencing worldly desolation and disaster and Yeats’s poem “The Second Coming.”

Encapsulating all this doom and gloom are twelve expertly-crafted pieces of music that echo Moby’s hugely successful trip-hop–meets-gospel sound of the mid-’90s, making the experience of listening to the album slightly disconcerting. Take the song “The Sorrow Tree,” for instance, which bubbles along with a sprightly keyboard riff on top of jittery trap beats; when the silky female vocals come in, the effect, in juxtaposition with the dark lyrical subject matter, is confusing. “Welcome to Hard Times,” on the other hand, does its title justice—it just sounds sad. Standout “Like a Motherless Child” combines two mainstays of Moby’s oeuvre we remember fondly: inspired female vocals singing a repeated chorus line and Moby’s deadpan talk-singing of the verse, the drums knocking out a delayed beat in line with random electronic noise. It’s a treat.

The record warrants a refocus on the periodic comparisons made between Moby and David Bowie, another thin white downtown Manhattanite. Like Bowie, Moby has consistently challenged himself by exploring new styles of music and looking for inspiration wherever he can find it, to varying degrees of success. Everything Was Beautiful, And Nothing Hurt is a delicious—if occasionally troubling—new wasteland for him to uncover.