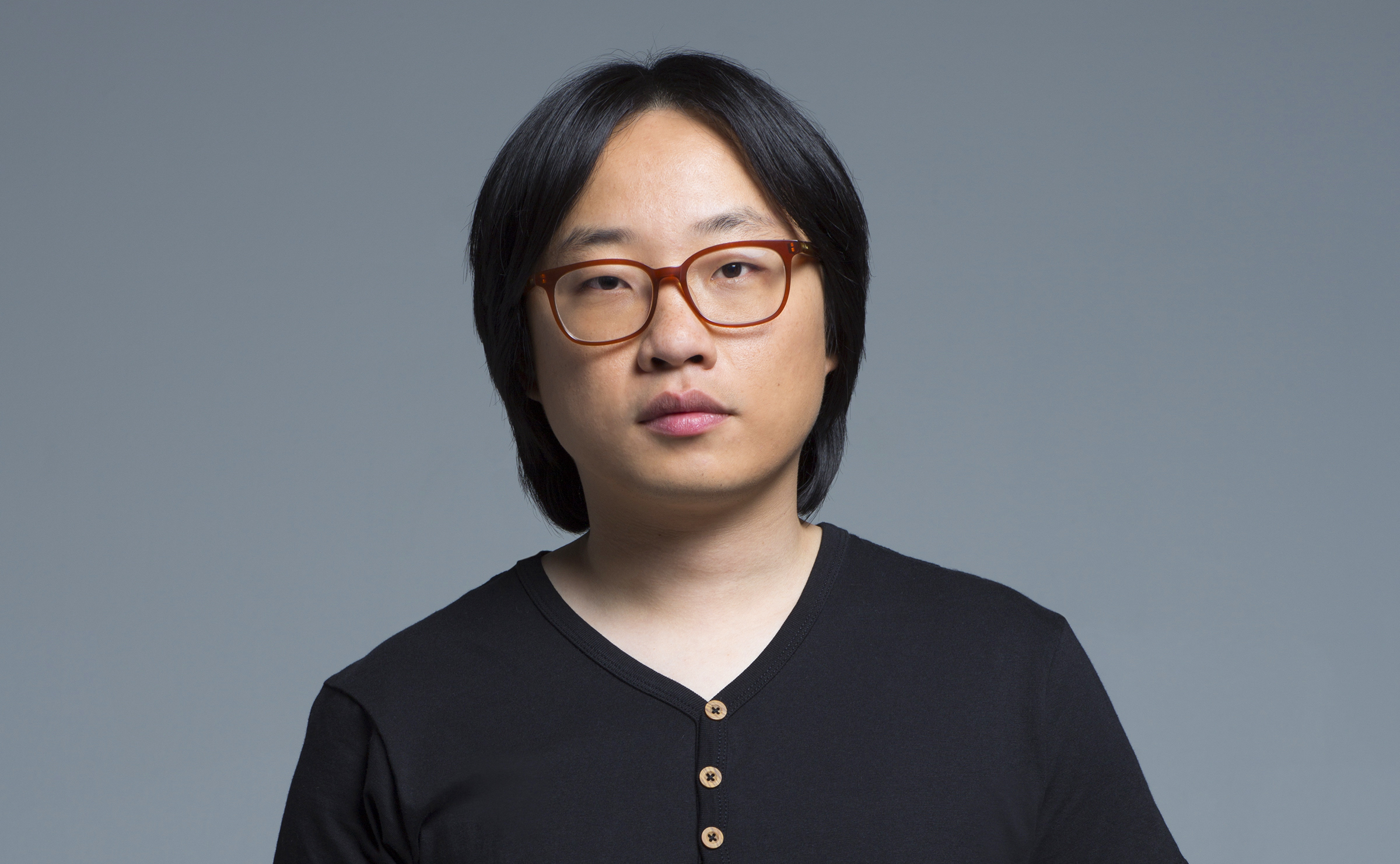

Jimmy O. Yang isn’t all that much like Jian-Yang, the character he plays on HBO’s Silicon Valley, which returned for its fifth season in March.

Unlike Jian-Yang, the real-life Yang isn’t casually cruel. On the show, Jian-Yang ruthlessly mocks his start-up incubator roomies, sparing no elaborate scheme to make them look and feel stupid. But the real Yang is a warm, tender guy, as evidenced by his new book, How to American: An Immigrant’s Guide to Disappointing Your Parents.

Riffing on the comic misadventures he amassed while evolving from young Chinese immigrant to stand-up comedian to strip club DJ to television star, Yang writes with an empathetic tone about his parents, his struggles with the opposite sex, and, of course, the lessons he picked up watching rap videos on BET. We spoke to Yang about what makes Jian-Yang tick, his new book, and his upcoming role in the eagerly anticipated rom-com Crazy Rich Asians.

The subtitle of your new book is An Immigrant’s Guide to Disappointing Your Parents. Are your parents any prouder to have an author for a son than they are a comedian?

I don’t know that they are proud of me for any of it. I’m still not a scientist, so it doesn’t matter, right? I think they just don’t get it about being an artist, but they’ve come around. I’m safe and sound now, so it’s all good.

You write about your relationship with your parents a lot. Did writing the book offer you a chance to open up to them without having to necessarily sit them down and walk them from point A to point B?

I think subconsciously, writing this book was partly like therapy… [I was able to] broach subjects I wouldn’t normally talk about. With Asian parents especially, we don’t ever say “I love you” to each other. We don’t ever talk about our emotions. That’s a very first-world thing that we don’t do. I’m interested in what they have to say about this, and maybe opening up that conversation, but most importantly I hope other immigrants or any type of outsider—anyone going through trying to fit in, assimilating, trying to teeter between two cultures, either Chinese-American or whatever—can relate to this book and feel a little better about themselves after reading it.

There is no shortage of funny people on Silicon Valley, but your role is one of my favorites. What did you think about Jian-Yang when you first read the scripts?

“There are people like [Jian-Yang] out there—like me, back in the day—and it should be our job to make these characters human, funny, and make them sexy or whatever.”

I really loved Jian-Yang’s character. I gravitate toward a lot of immigrant characters. It’s the same thing I did in Patriot’s Day: I played a character based on a real-life Chinese immigrant. I think a lot of Asian-American actors have reservations when it comes to playing fresh-off-the-boat characters—immigrants or somebody that has an accent—for fear of being a stereotype. But for me, this was me ten to fifteen years ago, when I first came to this country. I couldn’t speak English very well. I could totally relate to him and I pull a lot from that to put it into that character.

I don’t think my job is ever to avoid playing immigrant characters; I love playing him. There are people like that out there—like me, back in the day—and it should be our job to make these characters human, funny, and make them sexy or whatever. To make them three-dimensional.

The show is sort of about a lot of people who can’t communicate with each other. All of the characters struggle with that—Jian-Yang isn’t the only one dealing with it.

I think in the beginning, it was a satire on Erlich [Bachman, played by T. J. Miller]—him being short and impatient toward this little immigrant kid. The joke’s really on him. But as it progresses, I think the audience started to like the revenge of Jian-Yang. He’s been bullied so much—now they’re cheering for him. He’s the underdog.

In the book, you write about your attraction to rap music and BET, specifically. Of all the channels to latch on to, what was it about BET that hooked you?

It was just something I’d never seen before. I had never really heard rap music, never seen those music videos, never seen stand-up, right? So when I saw that, it wasn’t only educating me about the English language and slang, which I was very foreign to—it was also educating me about the culture of America. I didn’t know the stereotypes. In a comedy routine, when someone would say, “Black people do this, white people do that, Asian people do this…” I didn’t know those things. In Hong Kong, everyone is just Chinese. It was very interesting to me. It was a cultural education. I thought if I could just understand what they’re talking about, and what they’re saying, and how they’re saying it, I could get a pulse on what America’s really about.

You write about performing in San Diego early on in your stand-up career, and the audience is shouting racist taunts. You started your set by saying, “What’s up, racist motherfuckers?” That’s the most direct and incisive thing you could possibly have done, but I don’t think that would have been most people’s first move.

I think sometimes you’ve just got to call the crowd out on what it is. Same thing with improv. You’ve got to call somebody out for saying something crazy, and that’s where a lot of the comedy comes from. When it comes to a crowd like that… That’s something where they are racist motherfuckers and idiots and you’ve got to call it out as it is. You can’t be scared of them or else they’ll eat you up. I don’t necessarily think it’s a courage thing—it’s just a developed skill of comedy.

Does that sort of thing come naturally to you? Have you always felt like a pretty open person who’s unafraid of talking about who you are or what you’re thinking?

“In a comedy routine, when someone would say, ‘Black people do this, white people do that, Asian people do this…’ I didn’t know those things. In Hong Kong, everyone is just Chinese.”

I didn’t have too much stagefright, but I don’t think anyone is funny when they are starting out. You have to go onstage seven nights a week and grind it out. I wasn’t a very open person. Being Asian, like I said, we don’t talk about emotions like that. When I was first doing an acting class, my acting teacher realized there was a wall for me: I was starting to be kind of funny, but I still wasn’t talking about really truthful stuff—I was just making stupid jokes. My acting coach was like, “I can’t help you with this. You need to go see a therapist. That’s beyond my reach.” I actually went to see a therapist to get more opened up. My stand-up is more truthful now, and I think you need that, especially as an actor.

The exit of your former castmate T. J. Miller is very complicated. A lot of what I’ve read indicated that he wasn’t always the easiest to work with on set. He was your consistent foil on the show. What did it feel like knowing he was leaving?

He’s my boy. I was sad to see him go. I was the first person he called, and he said, “I’m not coming back on the show.” I was kind of shocked. I tried to talk him into coming back just for a few episodes, but I knew his mind was made up. At first I was worried. I didn’t know where my character would go. It’s so much me and him. My character almost never had a scene without him. We worked so well together, you know? Like Karl Malone and John Stockton.

But I think it became a blessing in disguise. It allowed my character to interact with more of the world and more of the other characters. I don’t know if we’ll ever find that same dynamic, but we’ve found some other really funny stuff that we’re exploring this year. You’ll see me making bigger, more powerful enemies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1d7vrmeF-nY

You’re starring in Crazy Rich Asians, which is out later this year.

I called my managers when I heard the news that the movie was being made and said, “Look, this is a full Asian cast, it’s huge, I don’t care what you’ve got to say, let me at least try to read for the lead part.” And my managers, who are amazing, kind of just leveled with me. They got real quiet and said, “Look, Jimmy, I don’t know how to tell you this, but for the lead part they’re looking for a good-looking guy.”

I was like, “OK, I get it.” [Laughs.] I’ll settle for the funny part. I actually auditioned for another part, and ended up with the Bernard Tai part. He’s a massive asshole, a frat boy, insane… So I had a lot of fun playing that.

When are we going to get to see you be really nice and charming?

In real life, baby! I’m such a nice guy in real life, that’s why I play assholes in the movies and TV shows. I don’t know, maybe I am an asshole in real life. Who knows? FL

This article appears in FLOOD 8. You can download or purchase the magazine here.