As far back as I can remember, I have been haunted by photos of Great Whites. Gnashing teeth, muscles swole beneath bulking frames, lifeless black eyes (“like a doll’s eyes,” says Robert Shaw in Jaws’ quietest scene). As if still pictures weren’t enough, there also exists a slow-mo sliver of nightmare courtesy of BBC’s Planet Earth: a high-def clip in which a Great White “breaches” five feet into the air, emerging beneath and swallowing whole a chubby seal off the coast of South Africa. Its mouth is a gaping enormity, pink and gummy, lined with rows of perfect isosceles. Its tail curls as the taste of blood soaks its tongue, and the whole thing slams back into the sea.

The worst place in America for shark attacks is Florida—because most sharks prefer warmer water—but anywhere with a coastline is fair game. California has had just 122 shark attacks since 1837 (when we began recording data), and in 2017, there were eighty-eight unprovoked shark attacks worldwide, only five of them fatal. (It remains unclear what a ‘provoked’ shark attack might entail—perhaps taunting the shark about his fin size or his momma.) Those numbers are meant to comfort, paltry in comparison to car crashes and myocardial infarctions. You’re more likely to be felled by a cow than a shark.

Cows, though, stand about in fields with droopy udders, chewing cud, while sharks are bred for bloodshed. The idea of sharks infected our collective consciousness long ago, and ideas are too potent to be disavowed by statistics. Sharks don’t have passions or hobbies—they live to eat, and eat they must. Some value communal living (hammerheads swarm in packs), but Great Whites typically slink through the depths solo. They don’t even sleep, as many have gleaned from Annie Hall’s breakup scene; sharks do have restful periods, but most remain in constant motion to keep water flowing through their gills or risk suffocation (“I think what we’ve got on our hands is a dead shark”). Another heartening factoid bandied about is that sharks don’t want to eat people. They may take a bite out of you when curious, but once they’ve realized you are not a seal, they will be embarrassed and apologize. (Still: Blood loss from a tentative bite can be deadly, and loss of limb is trauma enough for any lifetime.)

Former adult actress Stormy Daniels described Donald Trump as being “obsessed with sharks. Terrified.” She recalled the president watching Shark Week during one of their (alleged) raunched-up trysts: “He was like, ‘I donate to all these charities, and I would never donate to any charity that helps sharks. I hope all the sharks die.’” Spoken like a stable genius.

“He is obsessed with sharks. Terrified of sharks. He was like, ‘I donate to all these charities, and I would never donate to any charity that helps sharks. I hope all the sharks die.’”

—Stormy Daniels on Donald Trump

Trump and I have this fascination in common, though my intentions aren’t nearly so murderous. Sharks are the bouncers of the sea, the rough-and-tumble guardians, monsters as fearsome as dinosaurs or Cthulhu but wholly possible and visible and necessary, despite their global population decrease over the last several decades. The mythic sensationalism with which we now revile sharks, ingrained in us by Steven Spielberg and further perpetuated by Shark Week (celebrating its thirtieth anniversary this year) doesn’t help foster public sympathy for the beasts. Despite what we see at the movies and on TV, sharks don’t seek revenge or hunt humans for sport. Quite the opposite: Millions of them are killed by us every year. They are apex predators, at the top of the food chain, and thus exist as an integral part of marine ecosystems, helping keep populations healthy and controlled.

Jaws (1975) was the pioneering summer blockbuster and reviver of a formerly dull seasonal slog at the movies. Most people didn’t fret too gravely about What Lay Beneath before Spielberg’s behemoth bit them in the psyche. The author of the book Jaws (and co-writer on the film), Peter Benchley, came to regret his fiction’s fear-mongering in later years, devoting much of his life to ocean conservation as a kind of penance. “I see the sea today from a new perspective, not as an antagonist but as an ally, rife less with menace than with mystery and wonder,” he said.

Spielberg’s first masterpiece both is and isn’t a shark movie. Most notably, of course, the story surrounds a man-eating shark terrorizing a summer resort town, and the three men who try to stop him—but the shark is a red herring, a metaphor. Jaws is about American machismo and men who tear themselves apart trying to be heroes, hoping to conquer that which is big and unwieldy and uncontained. It’s about the easy denial of those in power, when that denial leads to personal gain. It’s about the hubris of assuming a problem can be staved off indefinitely. And it’s about greed, the nasty consequence of capitalism, the cost of human lives.

The shark is beside the point in Spielberg’s shark movie, and no shark film since has matched his complexity of narrative (though auteur distributor A24 expressed interest in taking on a shark project, so that might change). Jaws is slow, too, even aggressively contemplative in some parts—while the majority of shark films after it have veered into crude action-adventure territory.

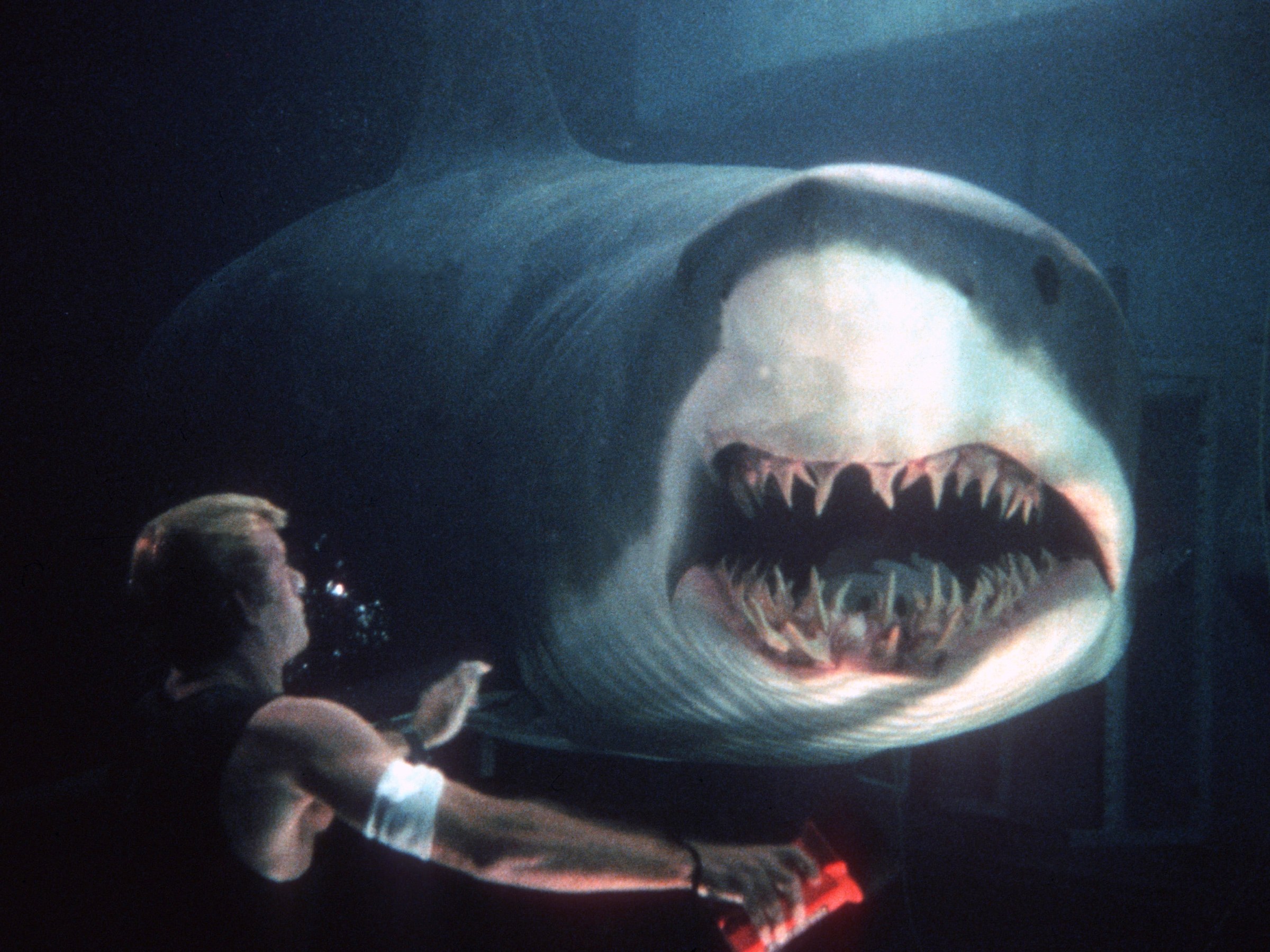

That is not to say there are no more good shark films, triumphant in a different sense. Deep Blue Sea (1999) is the oldest, a trailblazer in its own right, directed by Cliffhanger’s Renny Harlin: Campier and more moronically fun than Jaws, the sharks here are scientifically engineered to be smart, something Spielberg’s Bruce certainly never was. In a remote underwater research facility, scientists have altered the brains of three Makos in order to reactivate dormant brain cells similar to those in human Alzheimer’s patients (yes, the conceit is nonsensical).

The problem is that these research sharks are now problem-solvers, successfully flooding the center and killing most of the people inside with an endgame of escape; reaching the open water, exploring the deep blue sea. The workers trapped in the sinking facility aren’t money-grubbing philistines like the mayor in Jaws, who insisted on keeping the beaches open—these guys are trying to cure Alzheimer’s, a noble goal, even if their proceedings aren’t exactly ethical. Deep Blue Sea is about another kind of hubris: that of scientists believing they can subdue Mother Nature. It’s true we’ve browbeaten her, demolishing rainforests and melting her icecaps, but time is on her side. She has the luxury of waiting us out.

Jaws is about American machismo and men who tear themselves apart trying to be heroes, hoping to conquer that which is big and unwieldy and uncontained.

Several minimalistic human dramas structured as shark films tailed Deep Blue Sea, not precisely scary but dread-inducing instead; Open Water (2003) and The Reef (2010) are the best of this kind, both based on true and nasty events. In the former, two divers are mistakenly left behind in the open ocean following a scuba expedition; in the latter, a few Australian yacht riders strike a coral reef and capsize, leaving them stranded. Both stories feature the imminent arrival of some hungry Great Whites, drawn to blood in the water. These are survival tales, trafficking in desolation and foolish mistakes that should have been avoided, ruminating on the nature of chance and bad luck and how simple everything becomes when it’s just you left alone with the infinite sea.

The genre has seen increased experimentation over the last half-decade. Sharknado (2013) was made for the SyFy channel, but quickly garnered a cult following owing to a ludicrous plotline and wretched acting from Tara Reid and some other people who claim to be actors (I have my doubts). In this one, a waterspout—basically an ocean tornado—hurls hundreds of sharks from the ocean onto the streets of Los Angeles, where they soar through windows, crush people on the street, and chew the tops off cars. There are no stakes, and it matters not who lives or dies. One character even cuts his way out of a shark’s stomach with a chainsaw. The whole thing is absolute lunacy, helped along by the worst CGI since The Mummy Returns. But in that chaos, there is poetry. There are also five Sharknado sequels.

Jaume Collet-Serra’s The Shallows (2016) couldn’t be more different. It’s probably the first shark art film, replete with travel porn cinematography and a sun-kissed Blake Lively in isolate survival mode, doing battle with a Great White after she’s been bitten and stranded on a rock near shore. The (surprisingly respectable) computer-generated shark makes one hell of an entrance, cutting straight through a turquoise wave to knock the surfer off her board; in a gorgeous later scene, it pursues Blake through a field of glowing jellyfish. This is the rare shark flick without a boyfriend or best friend or crew of co-workers picked off one by one, as Blake is alone, exempting an injured seagull who joins her on the rock and puts in a subtly moving supporting performance.

Blake’s character is pre-med, but disillusioned with the medical field following her mother’s death by cancer, and the secluded Mexican beach from whence she sets sail was her mother’s favorite. By the film’s conclusion she has faced death and renewed her passion for medicine, as due in large part to her training, she’s able to survive the shark bite; stitching up her leg wound with a pair of earrings, constructing a tourniquet from her wetsuit. The Shallows is admittedly a little male gaze-y—Blake’s long body is tanned and frequently panned—but the foamy waves rolling into shore and dappled sunlight blinking off the water are every bit as sexy as their human co-star.

The Shallows is probably the first shark art film, replete with travel porn cinematography and a sun-kissed Blake Lively in isolate survival mode.

47 Meters Down (2017) came out one year later and starred Mandy Moore, the Blake Lively of the aughts. Originally slated for a home release, the studio pushed for a theatrical run after The Shallows’ box-office success, hoping to capitalize on the raging Sharkaissance. Unique in combining shark attacks with claustrophobia, 47 Meters Down features a pair of sisters cage-diving with Great Whites on vacation; at least until a chain snaps, and their cage plummets from the boat to the bottom of the ocean. Scuba tanks running low on air, the sisters must somehow reach the surface again before the sharks get them or they drown. The film is shot largely in the murky depths, one hundred and fifty feet down, illuminated only by dim lights on the girls’ diving masks (this blackness helps hide the cheap-looking sharks). The premise is also a wise nod to the performative tendencies inherent in our digital culture: Mandy’s character is a scaredy-cat, bullied into cage diving by her more reckless sister in order to prove she’s not boring. She plans to post photos of their adventures online and show her ex-boyfriend exactly what he’s missing. Needless to say, he’s lucky to have missed it.

This brings us to The Meg, in theaters now, a big-budget American/Chinese co-production that has defied box office predictions by scoring one of the highest debuts of the year (despite tepid reviews). “Meg” is short for megalodon, a prehistoric seventy-foot-long beast who went extinct over two million years ago; but what this movie presupposes is, what if it didn’t? The meg is a blowhard, much like our fearless leader who so fears her—for this shark is a ‘she,’ perhaps driven out of hiding by man-hating momentum. And she is very big. To give some perspective, a normal Great White is the relative size of a megalodon’s penis.

The Meg is incredibly stupid, though I watched it wearing a (mildly-inebriated) smile. It’s also a lazy crowd-pleaser: The audience cheered when a small pup managed to doggy-paddle away from the shark, though one literal baby, inexplicably in attendance at my screening, didn’t seem to enjoy the underwater carnage as much, and cried throughout. The film has a pleasantly diverse cast—including a poor man’s version of LL Cool J’s enduring character in Deep Blue Sea—and one visually exciting sequence involving a packed Chinese beach where scores of unsuspecting swimmers dangle their legs through colorful pool floaties (like this) as the shark approaches—but generally, the beige players and meaningless dialogue make for a forgettable experience. Most people remember the exact time and place they saw Jaws in theaters forty-three years ago, but I’ve practically Eternal Sunshined The Meg from my mind already.

It’s difficult to care about an oversize brute who threatens to devour an entire beach-full of tourists, but easy to care about a regular shark who might eat just one person you’ve grown to love.

The Meg isn’t really scary or smart or even purposefully stupid. Cheap special effects are partially to blame, but the size of the shark is the primary problem. She’s too damn big. We can’t relate to something the size of a school bus. It seems counterintuitive, but battling a smaller shark is more disturbing (and more intimate). Something about being on equal footing. It’s difficult to care about an oversize brute who threatens to devour an entire beach-full of tourists, but easy to care about a regular shark who might eat just one person you’ve grown to love. Like Trump, the Meg wants to be the Biggest, the Best, the Toughest. But nobody can be all that.

Ultimately, shark movies are nice because they are safe. Spirits, demons, sick serial killers, and mean little children can hunt you where you sleep, but not sharks. They are easier to avoid than “Hey There Delilah” or iPhone updates—all you have to do is stay out of the water. But to some of us, the ocean calls. FL