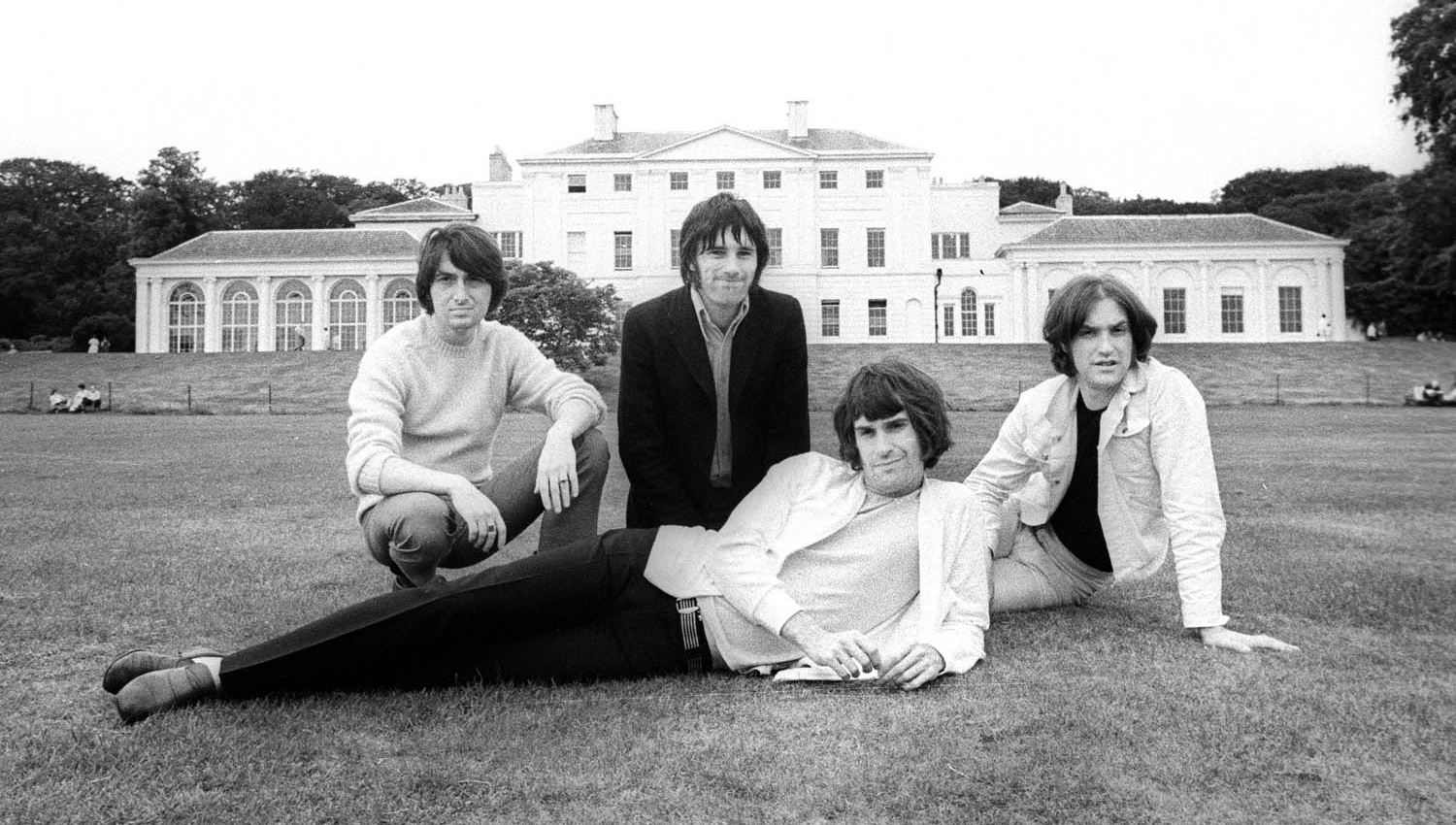

Fifty years ago this November, The Kinks released one of the greatest albums ever made…and almost nobody cared.

A witty, charming, and gorgeously melodic collection of fifteen songs about the fictitious denizens of a nameless English village, The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society was a staunch rejection of nearly everything that was hip and trendy in the British music scene at the time. While The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were earnestly singing about revolution, and Pink Floyd and other psychedelic bands were setting their controls for the heart of the sun, Kinks leader Ray Davies was writing songs that looked back nostalgically to a more innocent England of pastoral picnics and steam-powered trains, while also pondering weightier issues like cultural preservation, the existence of a higher power, and, oh, the meaning of life. Whimsical, philosophical, and utterly devoid of the heavy guitars, rebellious posturing, and stoned reveries popular in the angry days of late 1968, Village Green Preservation Society promptly sank like a stone.

“The week that Village Green was released, The Beatles’ White Album was out as well,” recalls Kinks cofounder and lead guitarist Dave Davies with a chuckle. “That album sold two million copies, and Village Green sold twenty thousand!”

The Kinks, of course, eventually had the last laugh. Despite its lack of initial commercial success, Village Green gradually assumed classic status over the ensuing decades, frequently praised as the band’s finest work by fans and critics alike. “The Village Green Preservation Society is a pop masterpiece,” writes no less of an authority than Pete Townshend, in an essay he penned for the lavish new fiftieth anniversary box set, which features remastered CD and vinyl versions of the album, as well as a wealth of non-LP recordings from the same period. An exhibition of photos, band memorabilia, and specially commissioned artwork inspired by the album (including paintings by Dave Davies) is also currently on display at London’s Proud Galleries through November 18.

This month also sees the release of Decade, a collection of previously unreleased Dave Davies solo tracks. Written and recorded between 1971 and 1979, the songs offer a glimpse into what was happening in Dave’s creative life during a time when his older brother was dominating The Kinks’ recorded output.

Dave spoke with FLOOD about Village Green, Decade, and the ongoing rumors of an impending Kinks reunion.

Village Green Preservation Society was The Kinks’ poorest-selling album of the 1960s. Is it gratifying for you to see how beloved it has subsequently become?

Oh, yeah. It was a very strange time for us as a band, but over the years a lot of writers and all sorts of people gravitated towards this album, which was really set apart from everything else that was out at the time.

Most of the Kinks fans I knew growing up weren’t even aware of the album’s existence; the people who were into Village Green were almost like a secret society.

Yeah! Well, when you listen to it, it is an invitation, in a way, to catch glimpses of this almost surreal world. It’s got some interesting Alice in Wonderland–type notions that go with the songs. It’s quite trippy, man, in a lot of ways! [Laughs.] Although it’s also about real things—whatever “real” is anymore. It conjures up a vision of community life in England that’s very emotional for me. As with Decade, the songs flash me back to memories and emotions I felt about real people that I grew up with…

So you still feel a sense of personal connection to these songs?

“[1968] was a time to reflect on the good things in the past, but also to try and think about the new things that were happening, and integrate both to build a happier, more harmonious future.”

Well, Decade, whenever I listen to it, is full of mixed emotions and my observations about my life at the time; I was going through a lot of inner change and inner turmoil about things. It’s a very personal album. With Village Green, obviously the songs are mainly Ray’s songs, but we worked on them very closely together, because the concept—the idea of an album about a village green—touched on a lot of characters we knew that weren’t too dissimilar to the people in the fictitious version of Village Green. The shopkeepers, the neighbors, the crazy old woman that lived down the road… “Wicked Annabella” is based on the crabby old lady that didn’t like kids running on her lawn, that kind of thing. I think a lot of the characters were based on real people, at some point. Thinking back over our lives at the time, growing up in Muswell Hill and Fortis Green, obviously there was a lot of nostalgia for the past and the people we knew, so that figured greatly in forming the characters.

Is the nostalgia of Village Green a nostalgia for a world you actually knew, or nostalgia for an era that pre-dated your existence?

Well, it’s probably both. Me and Ray were brought up in a big family with six older sisters and an extended family of uncles and aunts. My parents lived through two World Wars, which touched very closely on the heart of England—the working class. So there was quite a backstory behind these people who would pop their heads around the corner, as it were, many times throughout our childhood. And eventually, it formulated into Ray’s imagination.

Village Green is kind of about a loss of innocence, and a lot of…not regret, but thoughtful feelings about the past that maybe weren’t so bad. It was a time to reflect on the good things in the past, but also to try and think about the new things that were happening, and integrate both to build a happier, more harmonious future. And I think that’s the message of the album—the theme, really.

At what point did you realize that Ray was building this album around a specific theme?

Well, obviously, when Ray had come up with the song “Village Green Preservation Society”—it was very thematic in just the title. At this time, we were very close, and our families were very close; we used to see each other all the time, so I was privy to a lot of the stories and characters of that project. There was a lot of quirky things coming out of England in the ’50s and ’60s—these weird and wonderful English things that we thought were quite normal.

One of my favorite tracks on Village Green is “Wicked Annabella,” which you sing. What do you remember about recording that track?

Not a lot, really. A lot of these recordings were very in-the-moment. Ray would start working with the vocal, and I would learn the vocal… I always loved the bridge in “Wicked Annabella”—I always loved singing it, with the key change and everything. When I include it in my solo shows, my live shows, I do a version with two bridges, because it’s such a fun part to sing!

I’ve always wanted to know: Is that you singing the weird sped-up vocals of “Phenomenal Cat”?

“Is the universe a boat without a paddle? Or is some supreme being standing there? We all think of these things.”

What, the Mickey Mouse–type thing? No, that’s Ray; Ray’s singing that. I always thought “Phenomenal Cat” was a very psychedelic, kind of spiritual, mystical character, really. I like it particularly because it’s about strangeness—it’s about issues and feelings that we all think about. Is the universe a boat without a paddle? Or is some supreme being standing there? We all think of these things. I did a painting of “Phenomenal Cat” for the gallery exhibition in London, and I also did a painting of “Big Sky,” which relates to that theme, too—though all the songs on the album relate to it in some ways.

With the exception of “Wicked Annabella” and “Last of the Steam-Powered Trains,” the album doesn’t really rock in a conventional Kinks manner. Was that frustrating for you at the time?

No, I fell very happily into it! Me and Ray used to go to the pub with our families and play bar billiards and talk about football and the people we knew. It was all very much a part of the process of making Village Green—“Do you remember so-and-so?” that sort of thing. So yeah, I fell right into it. You have to remember that, throughout the whole Kinks career, the sound and subject matter has been very varied. It’s not just all hard rock; there’s light and dark and small and loud—every color you can think of. It’s like painting, you know? If you consider it like a movie, for instance, it’s like a whole story: You can’t do heavy, dark music constantly throughout it. You use it in a way to explain an emotion; it’s all covered with light and dark and all different kinds of things.

Were any of the songs on Decade ones that were rejected by The Kinks?

No. Strangely enough, I always thought they were incomplete, still in a state of being written. And the songs were very personal—I thought they maybe wouldn’t fit on a Kinks record, and I wasn’t going to have a big, drawn-out debate about them with Ray, because he was going through a very prolific time in a completely different direction. But I needed to get these inner feelings out, I needed to express myself. So I’m glad that, after all this time, Decade finally sees the light of day. Because it would have been a shame if these songs had never been released.

I don’t think most Kinks fans even realized that these songs existed—ditto for a few of the things on the Village Green box set!

Well, with The Kinks there was always something going on behind the scenes, a backstory or a secret life. And maybe we might still yet do something…

Any further talk of a Kinks reunion, then?

Well, I’m in New York at the moment, but when I’ll be back in London for the gallery event, me and Ray will be getting together to talk about this, that, and the other. So, we’ll see! [Laughs.] FL