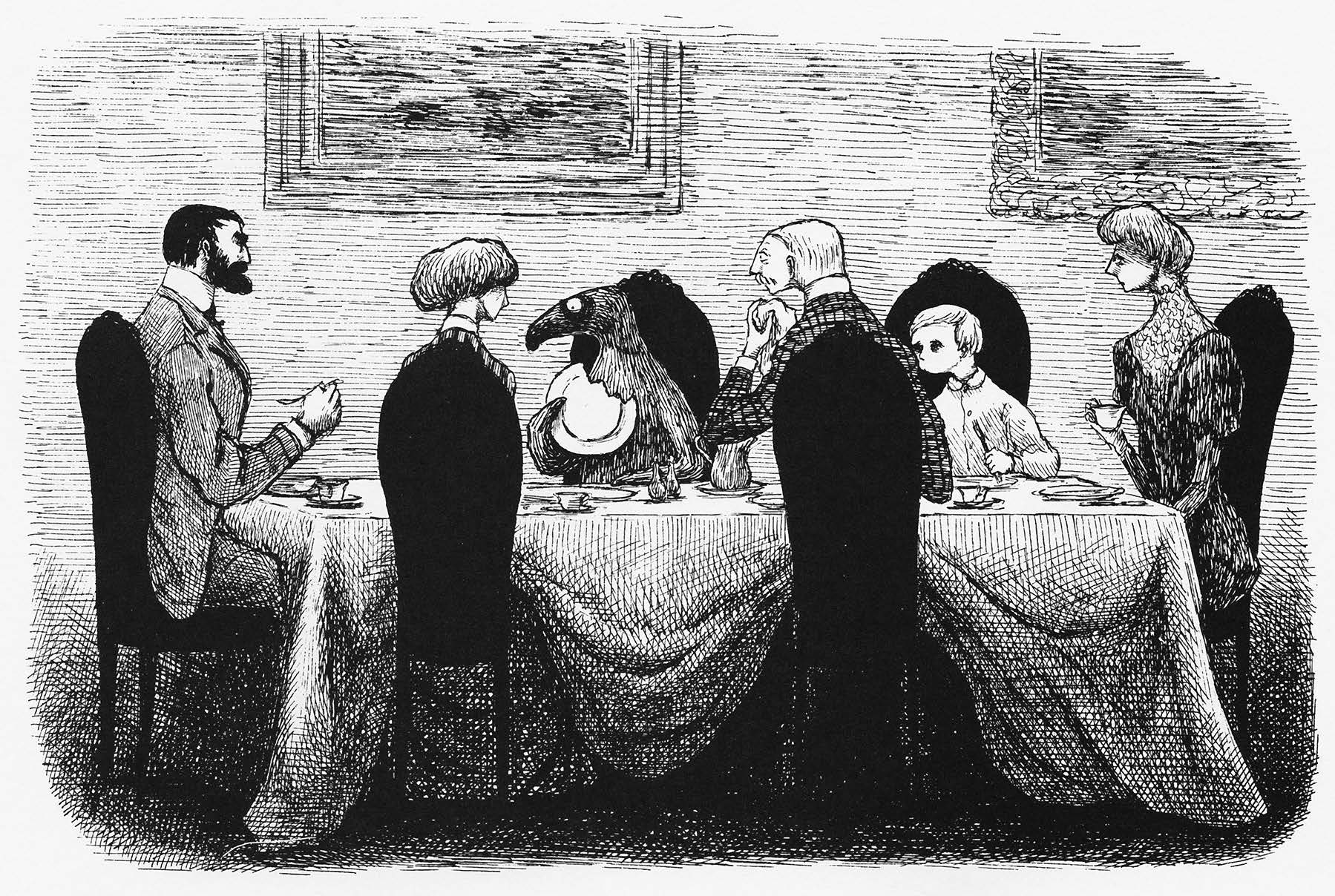

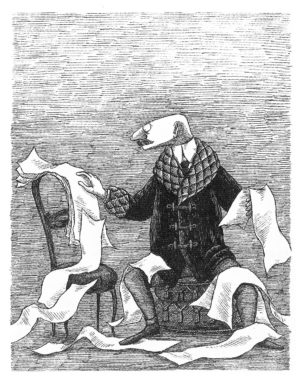

In tight, airless scenes, Edward Gorey characters wait. They stand on snowy lawns in lavish furs or pull up lonely chairs to a dining room table. They’re illustrated in sharp black strokes with enough cross-hatching to slice straight through the paper, and their dress and the surrounding architecture is a mixture of Edwardian fashion and the flapper ’20s, with a dash of the Victorian’s penchant for misery thrown in. You’ve seen Gorey’s influence in Tim Burton films, the fashion of Anna Sui, the novels of Neil Gaiman and Lemony Snicket, and on the racks at Hot Topic. (For the record: Hot Topic has never sold Gorey-specific items.) Gaiman even wanted Gorey to illustrate his Coraline, but the artist died the very same day the book was completed.

Born to be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey is the first full-length biography published on the artist. Its author, Mark Dery, has described Gorey’s “poisonously funny little picture books” as “deadpan accounts of murder, disaster and discreet depravity, narrated in a voice that affects the world-weary tone of British novelists.” Surprisingly, Gorey was not a cold, sardonic Brit at all, though he is often misidentified as such. He was the exact opposite: a Midwesterner, who eventually settled on the East Coast.

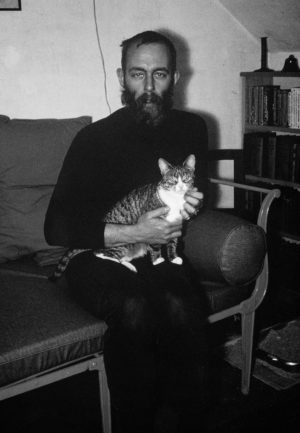

You can visit Gorey’s old house on Cape Cod, now a museum kept in his honor. The place was once crawling with cats—the most famous photograph of Gorey has him fast asleep in a room stacked with books and no fewer than three snoozing felines. Cats are spiteful, fussy creatures who’d prowl comfortably in Gorey’s world. (Dogs are too earnest and sloppy—more American than English in spirit.)

Gorey in 1961 / photo by Eleanor Garvey, courtesy of Elizabeth Morton collection

As an illustrator, Gorey infused gothic sentiment with black comedy. He was far darker than Tim Burton, who was born thirty-three years later and who, as I’ve written elsewhere on this site, has a sentimental heart beneath the macabre. Burton enjoys the threat of a child’s demise, while Gorey took delight in seeing that demise through to its bitter conclusion. His most famous work is probably The Gashlycrumb Tinies, an alphabet book in which, over the course of twenty-six letters, twenty-six kids succumb to their doom in merry rhyme: “C is for Clara who wasted away, D is for Desmond thrown out of a sleigh.” The funniest is N, for “Neville who died of ennui,” pictured as a small head peering out the window onto a bleak world. Gorey hearkens back to the Victorian era, wherein kids did shiver in rooms without heat, and died both often and early.

These drawings are dollhouse-cute if you don’t look too closely, the brushwork dainty and precise (his books were short and the corresponding artwork was small in scale, too; a master of miniature), but the content is not for the faint of heart. The most recognizable resemblance in tone is to Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—technically a fantasy as told to the author’s young niece, but also flushed with sinister chaos—and to the work of Edward Lear, the originator of literary nonsense, a Brit who popularized the limerick and the genre with A Book of Nonsense in 1846 before publishing his most famous work, The Owl and the Pussycat, in 1871. “If you’re doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because there’d be no point,” Gorey told The New Yorker in 1992. “I’m trying to think if there’s sunny nonsense. Sunny, funny nonsense for children—oh, how boring, boring, boring.”

Gorey was a loner, an only child who never married or lived with any partners. While he had many gay friends and qualities traditionally regarded as flamboyant—his love of camp, high stylization, ballet, silent film, elegant murder, and coy innuendo—he was presumed asexual, admitting to being “fortunate in that [he is] apparently reasonably undersexed or something.” In another of Gorey’s best-known works, The Doubtful Guest, a penguin-ish creature wearing a striped scarf shows up to an aristocratic house and refuses to leave the family alone for seventeen years, becoming more of a nuisance by the day. One might wonder whether this was how Gorey felt about having live-in company.

We spoke to expert Mark Dery about why illustrators and miniaturists get the short end of the art criticism stick, how the artist came to be so maudlin, and why Gorey didn’t date.

“The Unstrung Harp” (Little, Brown, 1953)

Gorey was an American—and a Midwesterner at that—though he became an East Coaster eventually. So how’d he get to have such a British sensibility?

Nothing could be further from “blighty,” as the English sometimes call their little island, than the Midwest. But Chicago is more gothic than you know. Gorey was born in 1925, and though his father had left crime reporting for the Hearst newspaper he worked at by the time Edward was born, he probably still saw him flipping through lurid tabloids of the day at the breakfast table.

Gorey grew up in Al Capone’s Chicago, where the chatter of machine guns was never far from the newsroom. Headlines were splashed with reports of gang slayings like the horrific St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. And then there was the ghastly Lindbergh kidnapping, which cast a long shadow across the American unconscious. We can’t really appreciate just how profoundly that reverberated in the mass mind. Charles Lindbergh was literally the most famous person in the entire world at that moment, so when his infant son was abducted from a second-story window and spirited away in the dead of night and later found a rotting, semi-dismembered cadaver in a snowbound field, it electrified the nation.

Maurice Sendak, a friend of Edward Gorey’s, never got over the trauma of the Lindbergh baby—he was obsessed with it his whole life. When Gorey was once asked by an interviewer, “Why is your work so macabre?” he gazed vacantly into the distance for a second, then after a dramatic beat said, “I really think I write about everyday life.” This is also someone who was prodigiously gifted: He started reading by age three and by age five had read both Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Not exactly a Yertle the Turtle.

I believe he came by his Anglophilia largely because much of his early reading was nineteenth-century novels and books like Edward Lear’s limericks—and crucially Alice in Wonderland and the darker Dickens, like The Old Curiosity Shop. All of that engraved a lugubrious, funereal sensibility on his infant imagination. One of repression, sidelong glances, furtive whispered conferences in corridors of country manors late at night.

Is there some quality of Gorey’s that, despite his dour English tastes, made him uniquely and clearly American?

He had a quintessentially modern aesthetic beneath the Victoriana and the Edwardiana and the roaring ’20s images. It’s very subtle, but it’s implicit: Gorey was a devout worshipper of the choreographer George Balanchine and his New York City Ballet. It’s a stripped-down neoclassicism that peeled away all of the nineteenth century bric-a-brac that had burdened ballet, the theatrical mannerisms and operatic sets. In the ’50s, Balanchine was doing ballet where the dancers wore nothing but black leotards and white t-shirts, and they began the dance with their backs to the audience. The music was this pungent, lunging, atonal Stravinsky stuff. Gorey loved those dances, so you see the modern and American in his fantastic distillation. His work is not baroque or over-the-top.

“For all of his ironic wit and whimsically gothic aesthetic, he’s very straightforward. He’s artificial, but not pretentious.”

A writer for The Washington Post once observed that people fixate on Gorey’s illustrations, but what is equally brilliant in his work are his beautifully balanced, periodic sentences, in which the most important word comes last, before the period. In these sentences, a world of meaning is compressed into a single pithy statement. Gorey’s Americanness can also be seen in his interest in the laconic and an absolute impatience with puffed-up preciosity. For all of his ironic wit and whimsically gothic aesthetic, he’s very straightforward. He’s artificial, but not pretentious. They’re quite different things.

Talk to me about the differences between illustration and drawing or painting. Gorey’s stuff is referred to, for the most part, as illustration. Do you feel that hindered him from earning the kind of critical respect he deserved?

I run the risk of a rant here—you’ve touched a raw nerve. Yes, there was a preposterous attempt by art-world gatekeepers of taste, who liked to determine what is fine art and what is mere “commercial art.” We’ve had, what, thirty years of postmodernism telling us there’s no difference between high and low? Marcel Duchamp famously said, “The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.” We’ve given the world the comic book, Chuck Berry, the Thunderbird… In American culture, there’s always been a healthy promiscuity between high and low culture. So what makes an illustrator? Presumably it’s someone whose primary impulses are commercial, but dear lord—Andy Warhol set out to become a zillionaire, and so did Salvador Dali! And people like Jeff Koons clearly have one beady eye on the bottom line. Thus, that distinction seems hypocritical at this point.

Gorey’s best work—his serious and philosophical books in which he’s asking searchingly deep questions about the meaning of life and the existence of God—for all of their brevity and apparently infantile form…I think that’s where many critics go awry. They see this minuscule format and lilliputian text and confuse that with triviality. They think it equates to frivolity. Gorey was determinedly frivolous, but very much in ironic quotes. As a Midwesterner, he had a reflexive distrust of anything that wore its learning too heavily. He was more like Roland Barthes, who said, “I like ideas held lightly that can be discarded in an instant.” Gorey’s version of that was to say, “When people are looking for meaning: beware.” That was all part of his pose as the Victorian idler; he must seem languid, insouciant, never breaking a sweat. And yet, Gorey worked fantastically hard. Some of his pieces required so much cross-hatching they took years to finish.

“I think that’s where many critics go awry. They see this minuscule format and lilliputian text and confuse that with triviality.”

I do think there’s a masculinist myopia in the art world that equates gigantism—a kind of phallic, looming monumentality—with substance and profundity. For example, sometimes women have worked on a very small scale, and that may be a psychic echo of the domestic sphere to which they were historically confined. You look at, say, the botanical and naturalistic art of Beatrix Potter, and it’s positively dazzling as scientific drawing, but stands on its own as artwork as well—yet it’s often dismissed, simply because it happens on a very lilliputian scale.

Gorey was presumed gay or possibly asexual. He had these crushes on and infatuations with men, but is it true he didn’t want them to go further?

Gorey always explained that away by saying: ‘You fall in love and your whole life goes floof!’ He positioned himself as a workaholic. It was Cyril Connolly who said, “The pram in the hallway is the enemy of good art.” In Gorey’s case, we can’t help but wonder if that wasn’t partly his way of deflecting the question.

Perhaps he preferred the idealized versions of people from a distance to the up-close mess of a real relationship?

Yes, I think he did. His crushes were, it bears pointing out, often on straight men. Another aspect which complicates things is that, while Gorey might have preferred the platonic ideal to the fallen reality, he was also a drama queen, who at one point sent the man he had a crush on a postcard with a quote from a novel saying, in effect, “My definition of a relationship is two people tearing each other to pieces.” He had this almost pathologically overstated vision of romance as a kind of acid bath in which you boil away everything about the other person that is pretension and surface until you reduce them to this pile of bones at the bottom of the bathtub, and that’s the truth of who they are. Of course, by the time you get there, you’ve destroyed the relationship.

Despite the picture-book nature of Gorey’s work and his similarities to Maurice Sendak, he was never considered a children’s author. Why do you think Sendak struck it big commercially despite the frightening nature of his work, but Gorey never did?

His publishers—and mainstream, commercial houses in the ’50s and ’60s—went ashen in horror at the thought of marketing Gorey to children, for fear that the sort of people who like to ban books would rise up in an angry mob. Gorey’s second book, The Listing Attic, is unimaginably perverse for that historical moment. This is Eisenhower’s America, presided over by the man Gore Vidal called “The Great Golfer.” It’s the America of the white picket fence and Revolutionary Road. And Gorey is doing a collection of limericks, which is a children’s form, but he’s appropriating it. There’s a limerick about a predatory vicar leering at a little boy, leading him quite literally down a primrose path “to practice vices we cannot imagine.” This is hair-curling stuff in 2018, so imagine how it would’ve sounded to a librarian in 1954. FL