Two months after The Beatles officially broke up, Ringo Starr decided to take a trip to Nashville. He’d spent the final tumultuous years of the group’s run as peacemaker (is it any surprise that his Twitter feed these days is a glorious sea of ?✌️???☮️?), so it was certainly fair to say that he’d earned some me-time—and plus, he’d never been there before.

That’s an odd detail to consider, given how The Beatles had gone around the world and back by the time they were old enough to grow mustaches, and it’s especially odd in relation to a city like Nashville, the footprint of which is found all over so many of The Beatles’ recordings, from “I’ll Cry Instead” to “The Ballad of John and Yoko.” In a sense, what Chicago was to The Rolling Stones, Nashville was to The Beatles—and yet, the lab-coat-engineered Abbey Road environment never really aligned with the fast-moving working-class ethos of Music City. The Beatles loved country music, but there was no reason to believe that they’d love the way that country music was made.

Ringo himself was in an unusual spot at this point, considering that he was simultaneously one of the most famous musicians alive and also a musician that no one really had grand expectations for. Appropriately enough, anyway, he then subverted those lower expectations by becoming the first Beatle to release a proper solo album—and he did it with one that sounded nothing like a Beatles record. At all.

Sentimental Journey, released just three months into the start of a new decade brimming with forward-thinking momentum, is an album of backward-looking standards. Surrounded by classical production from George Martin, Ringo sings like he’s goddamn Sinatra or something, without one bit of irony. (OK, maybe it was a little ironic.) The record flopped, of course—at least as much as any Beatles-related album can flop—and truthfully it hasn’t proven to be a particularly enduring musical artifact. But it did prove to be extremely endearing, regardless—at least in terms of illustrating that Ringo wasn’t afraid to do whatever the hell he wanted. John, Paul, and George each released their own traditional solo debuts in the coming months, and while those three albums were all stone-cold classics, they were also more or less what people were waiting for. Ringo was the only one to take the post-Beatles platform and immediately do something unexpected.

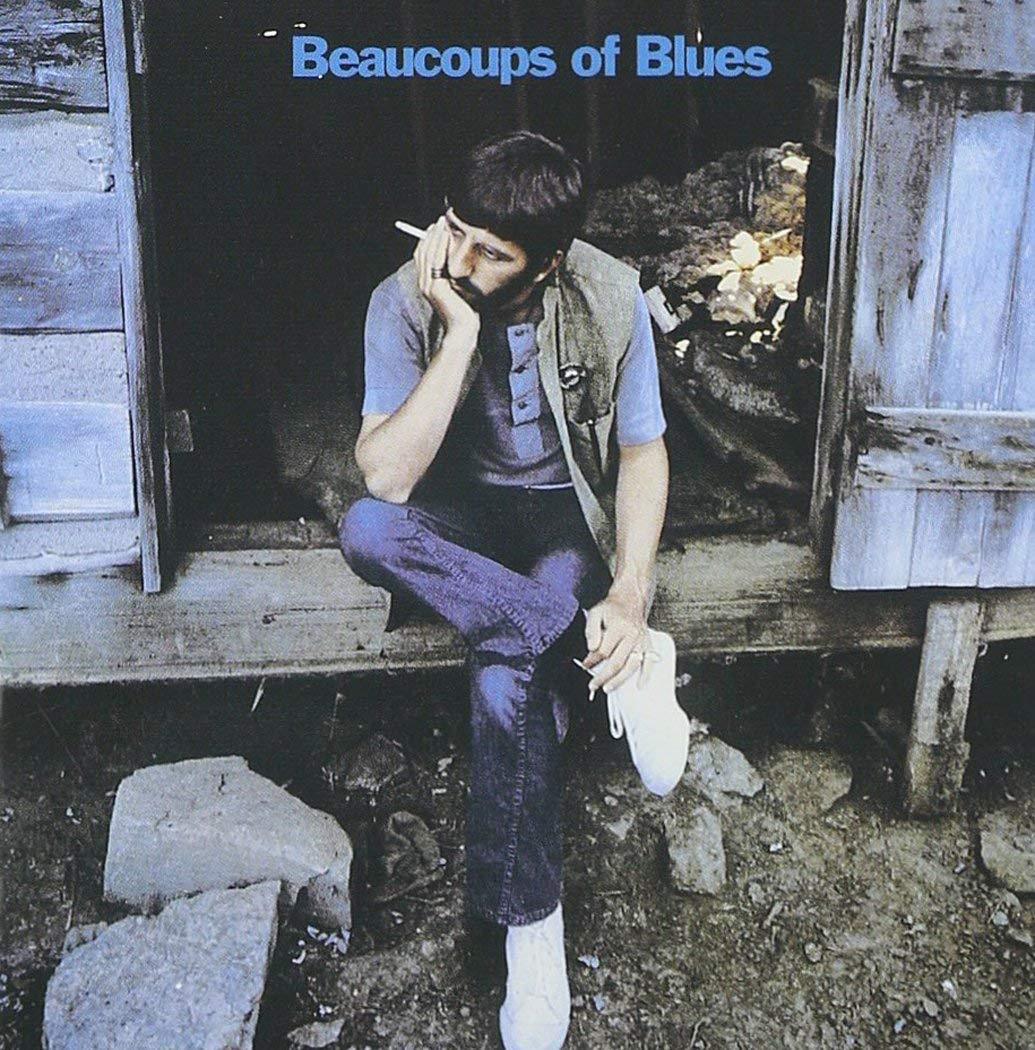

It was in that same spirit that he ventured to America for a much different brand of whimsy—and this time it was one that suited him perfectly. Beaucoups of Blues is pure Nashville—more Nashville than Nashville Skyline, even—and a pure slice of country joy.

Beaucoups of Blues is the Nashville sound’s interpretation of the Beatles’ Liverpool sound, which itself was a partial interpretation of the Nashville sound in the first place.

The story behind the record is appropriately spontaneous: Allegedly, George asked Ringo to pick up pedal-steel player Pete Drake from the airport in England so he could help on All Things Must Pass, and during the ride Pete noticed Ringo’s surprisingly extensive collection of country music in the car. Drake, who had recently worked with Bob Dylan on John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline, suggested that Ringo come out to Nashville and make a record with him, and Ringo, as advertised, was willing to roll with the unexpected.

Just a few weeks later, with Sentimental Journey still fresh on the racks, Ringo arrived to a factory of local firepower waiting for him in the South; Drake had arranged for a large and professional crew of Nashville’s finest musicians to make an album in one week’s time. Ringo thought he was mad to suggest such a short timeline—Abbey Road took seven months to make—but Drake was more than true to his word: They recorded the entire album in three days.

There’s something peculiar and shape-shifty about the sound of Beaucoups of Blues, and that’s likely related to the fact that it’s an album of originals that were written for Ringo, but not by Ringo. It’s the Nashville sound’s interpretation of the Beatles’ Liverpool sound, which itself was a partial interpretation of the Nashville sound in the first place. You get the sense that Drake played his songwriters “Don’t Pass Me By” to get Ringo’s range and cadence right, and then sent them off to individually write their own idea of what the “Ringo Takes a Trip to Nashville” vibe really should be.

Still, this is Nashville in 1970 that we’re talking about here, so naturally that means most of these songs are universally applicable sob stories about how much it sucks to fall in and out of love. But with your pal Ringo singing them, all those lines about heartbreak and drinking end up feeling insulating rather than isolating, and everything takes on an almost theatrical sound. It’s the musical equivalent of watching a movie starring someone who you know the part was written specifically for.

Ringo could have showed up in Nashville unable to cooperate with the less-than-luxurious nature of this operation—hell, he barely made it two weeks in India because of the food alone—but instead he thrived in it. It takes a selfless musician to come in to a studio with no prior material arranged and walk out a few days later with an album, no matter who you are. But this wasn’t just any old dude who did that: This dude was a star. FL